A few years ago, a Boulder woman who owned one of Colorado’s first dispensaries ran into some troubles with her bank. As she later recounted, the bank told her the money she was depositing into her business account reeked of marijuana. The bank was willing to take her money, but she would have to do something about the smell. Maybe Febreze would help. Her bank, in other words, asked her to literally launder her money.

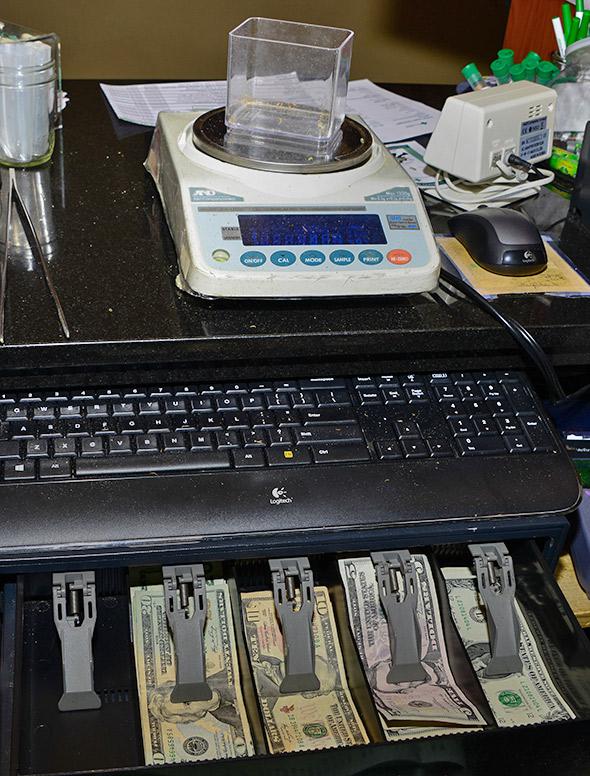

Since then, the relationship between marijuana businesses and their banks has only become more fraught and complicated. Talk to anyone involved in Colorado’s marijuana industry—regulators, market players, law enforcement—and they’ll likely agree that the biggest obstacle to bringing marijuana out of the shadows is the industry’s inability to obtain basic banking services. The few Colorado marijuana operations still lucky enough to have bank accounts jealously guard the specifics for the protection of everyone involved, and reports of banks unceremoniously dropping pot clients are commonplace. The front desk at Colorado’s Marijuana Enforcement Division is stocked with jumbo-sized money counters, since most marijuana businesses have no choice but to pay the tens of thousands of dollars in licensing fees and taxes in cash. The situation has become so vexing that members of both parties from Colorado’s congressional delegation recently joined together to urge Treasury and Justice Department officials to do something about it.

The problem is that because marijuana is still classified by the federal government as a Schedule I narcotic, anyone who facilitates the cultivation or distribution of the drug, even in states where it’s legal, is in violation of the Controlled Substances Act. Banks that provide financial assistance are therefore risking prosecution as co-conspirators or aiders and abettors. Plus, by taking money from an industry that’s still illegal federally, a bank could be guilty under federal money laundering statutes—not an attractive outcome for an upstanding, publicly traded business.

For a while, some banks were willing to work with marijuana businesses, even if they didn’t like the smell of their cash. That changed in June 2011, however, when the DOJ issued a stern memo threatening to prosecute on money laundering charges even those operations tangentially related to the marijuana industry. That led most banks to sever ties with the industry, and those that didn’t were extremely hush-hush about their involvement with marijuana growers and sellers. According to Michael Elliott, executive director of the Colorado-based Medical Marijuana Industry Group, those marijuana businesses that still have bank accounts try to keep multiple small accounts at different financial institutions. Having different bank accounts means you can spread the money around, which keeps your accounts from getting flagged for large cash infusions and gives you backups in case one or more of your accounts gets closed.

Last Thursday, Attorney General Eric Holder offered a shred of hope when he said pot businesses operating under the imprimatur of state law should have access to banking services and promised forthcoming government rules to help them do so. Still, it’s not as if the Obama administration can single-handedly change federal law; the most it can do is instruct prosecutors to not prioritize marijuana banking cases—and in the meticulous world of banking, that might not be enough to persuade banks to play ball with the marijuana industry. As Vanderbilt law professor Robert Mikos noted in an email, “I think the exercise of prosecutorial discretion (i.e., non-enforcement) only gets you so far. I can just imagine bank compliance officers scratching their heads over the idea of only having to comply with laws that are being enforced.”

The legal U.S. marijuana market is predicted to hit $2.34 billion in sales this year; it’s hard to conceive of any industry that size not having ready access to even the most basic of financial services. Why does that matter? One benefit of banks is the security they offer. And with all the marijuana-related cash exchanging hands in Colorado these days, security is a pre-eminent concern. It doesn’t help that there seem to be fewer and fewer people around to help guard that cash. Last summer, the Drug Enforcement Administration reportedly began pressuring armored-car companies to stop working with marijuana companies. And last month, the Denver Police Department barred its off-duty officers from working security at marijuana operations, despite the fact that many moonlight as security guards at liquor stores and bars. That’s because department policy prohibits off-duty officers from working with any business that “constitutes a threat to the status of dignity of the police,” such as porn stores, strip clubs—and now, pot shops.

“They’re setting marijuana up to be a cash business that can’t protect itself,” says Elliott. “The roles have switched. Now the marijuana industry is the one working to keep things safe.”

Another service banks provide is loans—and that’s something Colorado’s marijuana industry desperately needs. Because Colorado imposes residency requirements, background checks, and other limitations on marijuana licensure, pot shops can’t easily raise capital the way other startup businesses usually can—by selling a part of the business in exchange for ready capital. This has led to some novel solutions, such High Times’ recently announced private-equity fund to help cannabis businesses that can’t get business loans.

But marijuana businesses shouldn’t be expecting loans from banks anytime soon. Even if banks weren’t worried about possible money laundering charges, there’s the problem of what they could accept as collateral for a loan. They aren’t likely to take a marijuana business’s tangible property like vehicles or buildings, since that’s all subject to forfeiture if the feds change their minds and start enforcing federal drug laws. Nor, of course, could they accept the business’s inventory (i.e., the pot), or take over the running of the business themselves. A Wells Fargo–run Grateful Meds? Unlikely.

Then there’s the other financial conundrum facing marijuana stores: what to do about credit cards. Historically, credit card companies have been as wary of pot as banks, fearing that any financial transaction with those violating federal law could be seen by prosecutors as engaging in money laundering. Lately, however, some major operators have been fudging the rules. Earlier this month, Visa issued a statement noting, “Given the federal government’s position and recognizing this is an evolving legal matter with different standards applicable in different states, our local merchant acquirers [i.e., banks] are best suited to make any determination about potential illegality.” That’s why some Colorado banks are working with pot shops to allow them to take plastic—but doing so requires some questionable financial footwork, such as either processing the card transactions as if they were ATM withdrawals, or possibly even relabeling the transaction so it doesn’t appear to be a marijuana purchase. As Ean Seeb, co-founder of the Denver Relief marijuana consulting company, puts it, “There are people who have credit card services in this industry, but for those who do, somebody somewhere is lying to someone else, and that someone is violating the law.” However companies are getting credit cards to work, the arrangement appears untenable.

That’s why some people in the marijuana business are dreaming up alternatives to traditional banking services, both to help the industry and to take financial advantage of the void left by banks and credit cards. Some of these concepts involve new technologies, such as point-of-sale “cashless ATM” debit machines that deduct payments (plus a surcharge) from customers’ ATM cards, and payment devices that secure cash in a lockbox as soon as it leaves the customers’ hands. Then there’s the idea floated by some legislators and marijuana stakeholders of creating a state-owned, marijuana-focused bank with no connection to the federal financial system, an undertaking that would be exceedingly difficult (it couldn’t issue debit or credit cards, couldn’t accept checks or funds from other banks, and wouldn’t be insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation), plus might not even be legal, since many state constitutions appear to preclude state-owned banks.

All of these options are at best stop-gap measures, temporary fixes until the government gets around to solving the real problem—amending the Controlled Substances Act, and possibly other federal statutes such as the USA Patriot Act and the Bank Secrecy Act, to allow for marijuana-related financial transactions. Because, as a recent, little-known Arizona court case called Hammer v. Today’s Health Care II made clear, when it comes to dollars and cents, there’s no getting around the federal criminality of pot. In August 2010, two Arizonans lent $500,000 to a Nevada-based corporation called Today’s Health Care II, or THC, to operate a medical marijuana dispensary and grow center in Colorado. Court documents indicate that THC stopped making payments on the loan and defaulted in March 2011—which led the Arizonans to sue in Arizona state court for the enforcement of the contract. The judge in the case, however, dismissed the suit, buying THC’s argument that the contract was unenforceable because it was entered into for criminal purposes. That’s right: THC successfully argued that it did not have to pay back its loan because it was engaged in a violation of federal law.

While the case was a win for THC, it’s a disaster for the cannabis industry in general. We are a country built on contracts. Banking arrangements are built on contracts, loans are built on contracts, financial transactions are built on contracts. If all these marijuana-related contracts are unenforceable, the economic foundations of Colorado’s fledgling marijuana economy could be on shaky ground.

Next up: So far, everything’s gone relatively smoothly for Colorado’s legal marijuana experiment. But is it all clear sailing ahead? We look at how this could all still go terribly, terribly wrong.