One afternoon last February, a group of policymakers hand-selected by Colorado’s governor sat in a public meeting room in Denver and took up the subject of marijuana gummy worms.

Should marijuana gummy worms, which look like the old-fashioned penny candy but come laced with cannabis, be outlawed? If not, how should they be differentiated from the kid-friendly, nonmarijuana kind? Should marijuana gummy worms come only in dull, unappealing colors, as someone suggested—should they, in other words, be more worm-like? And how should the potency of these worms be measured and labeled? What if some worms are more potent than others? What if the tail is more potent than the head?

These are the sorts of questions the state of Colorado has been struggling with since its voters passed Amendment 64 in November 2012, putting the state on a fast track to doing something no polity has ever done before. On Jan. 1, Colorado will become the first state in the modern world to legalize marijuana from seed to sale. (Uruguay voted on Tuesday to legalize pot, but the law won’t be implemented for 120 days. In the Netherlands, marijuana is simply decriminalized, not legal. While Washington state legalized marijuana at the same time Colorado passed Amendment 64, its regulatory system likely won’t be up and running until next summer.) That means Colorado’s lawmakers, businesses, and citizens are facing issues no one has tackled before. How do you legally produce marijuana? What procedures should be put in place for its packaging, transportation, sale, and taxation? How do you keep track of all that pot, and how do you discipline those who run afoul of your regulations? How do you regulate the financing of pot operations, the development of peripheral businesses, the marketing of marijuana to tourists? And how do you keep the whole thing from falling apart? In short, how do you build an entire industry from scratch?

Over the next two months, as Colorado’s legal pot industry opens for business, the two of us—Sam Kamin, a University of Denver law professor, and Joel Warner, a local writer—will look at how Colorado is answering these questions, with the world watching and possibly billions of dollars at stake—not to mention the federal government keeping a close eye on everything. Marijuana, after all, remains a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Substances Act, alongside LSD and heroin. That means Colorado has to figure out a way to abide by its voters’ wish to authorize marijuana’s possession, manufacture, and sale without causing the feds to act on the fact that all of these actions are still punishable by up to life in prison.

We’re beginning our coverage with the most important issue Colorado has had to wrestle with so far: How do you build a regulatory framework for pot? All other decisions on legalized marijuana derive from this one. Pretty much every legal good and service is regulated in one way or another—restaurants are inspected, plumbers are licensed, sodas have to list their ingredients—and marijuana is a psychoactive substance, like cocaine, alcohol, and sleeping pills, so clearly there have to be rules about how it’s used. Even marijuana’s most ardent proponents concede there have to be limits on its sale and usage—children shouldn’t have access to it, people shouldn’t drive under its influence. But the biggest argument of all for marijuana regulation, from the government’s perspective, is taxation. If the state doesn’t know who is selling it, where they are selling it, or who’s buying it and at what price, Colorado can’t make any money off it.

To determine the best way to regulate this new market, a week after the law passed, Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper formed the Amendment 64 Implementation Task Force comprised of elected officials, stakeholders in the state’s existing medical marijuana industry, and various experts (including one of us—the University of Denver’s Sam Kamin). It was no easy task, especially since Colorado had just over a year to pick a regulatory model, pass legislation implementing it, conduct rulemaking around it, and go through all the licensing and inspections required to implement it by Jan. 1. Compared to how long most governmental processes take, that was a blink of an eye.

Courtesy of Ry Prichard

Given such pressures, the state’s best bet, the task force decided, was to borrow from existing regulatory models. But which set of rules were the right fit? What legal substance does pot most resemble?

The most obvious parallel was alcohol. Amendment 64, after all, explicitly invoked alcohol regulation as its inspiration, and its supporters built their campaign around a simple, catchy idea: Marijuana is safer than booze. When the measure passed, many people compared the moment to the end of Prohibition in 1933. But do we really want marijuana to be treated like alcohol? On the one hand, alcohol is carefully controlled, which would prove helpful for marijuana. Sellers have to be licensed, manufacturers must list their products’ potency, and rules are in place to prohibit sales to minors. On the other hand, there’s no single alcohol distribution model for marijuana to emulate. For example, liquor stores operate independently of alcohol manufacturers, and shoppers aren’t allowed to consume purchases on site. But at some breweries, the opposite is true—the beer is produced, sold, and consumed at a single location. So which should it be: pot package stores or pot brewpubs?

And there’s a larger concern with modeling marijuana legalization after alcohol. While Prohibition failed to snuff out drinking and helped fuel organize crime, there’s no denying that in the free-market system that’s flourished since then alcohol use has surged. According to health statistics, today more than half of American adults are regular drinkers, and there are more than 80,000 alcohol-related deaths a year. While there’s no evidence marijuana legalization will produce any sort of similar mortality rate, do we want a free-for-all system that could encourage so many people to regularly smoke pot?

In light of these concerns, Colorado policymakers briefly considered a state-run program, similar to systems in New Hampshire and other states that manage their own liquor stores. This approach had several benefits. For one thing, studies show that state-run alcohol programs, thanks to their lack of targeted advertising and price competition, lead to significantly less spirit and wine consumption than free-market programs. For another, a state-run dispensary model would allow the state to reap the profits of marijuana sales, rather than just levying taxes and fees.

But even if a state-run marijuana program were theoretically the best approach, it came with a major problem: It would put Colorado in direct conflict with the federal government. It’s one thing to permit and even license a substance that’s against federal law; it’s something else entirely to require state employees, as part of their job, to violate that law.

That’s why the Amendment 64 task force ultimately recommended—and the Colorado legislature eventually passed in a 136-page set of rules—a regulatory model for pot that requires a vertically integrated supply chain. For at least the first nine months of 2014, Colorado pot stores will have to grow at least 70 percent of what they sell, while the rest can come from other producers. Similarly, Colorado marijuana producers will have to retail 70 percent of what they grow; the rest can be sold to other retailers. Under such a closed-loop system—retailers have to grow and vice versa—there is less concern that producers will grow as much as they can and then sell to any buyer they can find, lawfully or unlawfully. Plus, the high cost of vertical integration—leasing, equipping, staffing, and licensing both a grow facility and a retail store doesn’t come cheap—means the number of market participants will likely be limited, at least at the outset. Finally, Colorado would accomplish all of this without federally problematic state control.

Courtesy of Ry Prichard

But the vertical integration model is far from perfect. The system discourages competition and creates barriers to entry, which means less consumer choice and higher prices. Imagine if your local liquor store sold primarily Budweiser, with only a handful of other beers, as opposed to all the brands shoppers actually wanted. This is why Washington state’s marijuana program is going the opposite route, forbidding vertical integration. And it’s why since the end of Prohibition, the government has outlawed alcohol monopolies.

Still, vertical integration had one other important thing going for it in Colorado: The system was already in place. In 2010, Colorado had taken steps to rein in a booming medical marijuana industry that was largely unregulated. There was little control over who was growing pot, where it was being sold, and who was buying it. In response, the legislature passed extensive new medical marijuana rules that required dispensaries to grow 70 percent of their own product. All across the state, dispensaries and grow operations were forced to merge. Some of these shotgun weddings panned out, and some didn’t, leading to a more consolidated and stable medical marijuana scene. Suddenly, Colorado had the most robust regulatory regime in the country, allowing it to skirt federal busts that crippled medical marijuana operations elsewhere.

That’s why for the first nine months of 2014, the only Colorado businesses that will be selling recreational pot are those that were previously vertically integrated medical marijuana operations. (The city of Denver has extended its moratorium on new pot-shop licensees through February 2016). In other words, the state’s new pot regime will look much like the old one: the same people selling it, the same rules for how it’s produced, the same Department of Revenue regulators overseeing it all. The state policymakers ultimately decided if the system isn’t broke, perhaps it doesn’t need fixing.

But even with Colorado’s regulatory system nailed down, there are still plenty of wrinkles to be ironed. Among the more perplexing conundrums:

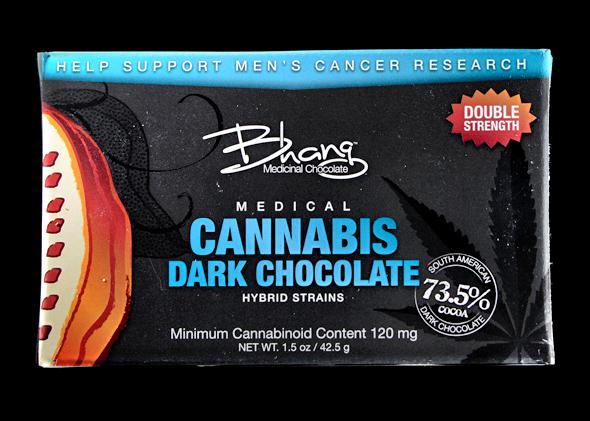

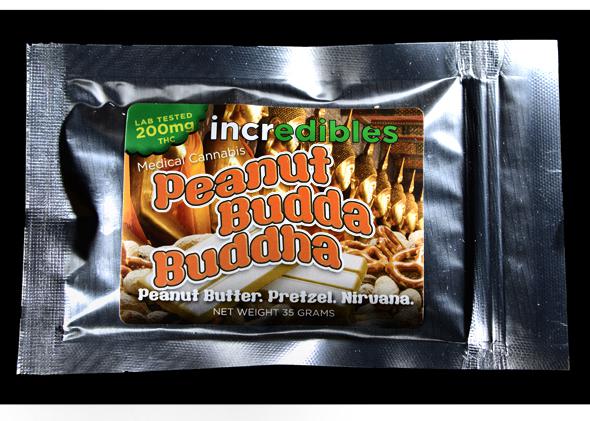

Warning symbols

Consider the marijuana lollipop, part of the smorgasbord of pot-infused candies, granola bars, and even sodas currently sold at Colorado marijuana dispensaries. How do you distinguish these pops from a run-of the-mill sucker? While a pot lollipop’s THC content isn’t going to cause anyone serious harm, no one wants the headlines that would come with a bunch of kids getting marijuana highs along with their sugar rush. That’s why, along with other labeling requirements such as usage instructions, ingredient lists, pesticides and chemicals used, and various warnings, marijuana products will be required to display a marijuana-related “universal symbol” that children who can’t yet read will understand.

Courtesy of Ry Prichard

But what should that symbol be? While adults the world over recognize the seven-pointed leaf as a symbol for pot, little kids aren’t likely to do so—and the image might even be enticing to them. The now-iconic “Mr. Yuk” poison symbol was created in the 1970s, because children associated the old symbol—a skull and crossbones—with fun stuff like pirates and adventure. So what’s the marijuana version of Mr. Yuk? That has yet to be determined, but the state’s new Marijuana Enforcement Division will need to come up with it soon.

Advertising

According to Colorado’s new pot rules, marijuana ads can only run in media outlets like periodicals and local television channels where there’s evidence that no more than 30 percent of the audience is under 21 (finally, an upside to print media’s growing unpopularity among young people). Outdoor ads like billboards and taxi decals are also prohibited. It’s a well-meaning idea, and it signals to the federal government that Colorado isn’t planning on becoming a stoner’s paradise. But the regulations likely won’t hold up in court, since less onerous restrictions on alcohol and tobacco ads have previously been overturned for violating the First Amendment. Does that mean Colorado will soon be plastered with pot-leaf billboards? Not necessarily, since it’s in the marijuana industry’s best interest to rein in excessive advertising, just as the tobacco and spirits industries have in the past adopted self-imposed advertising restrictions for public-relations reasons. No marijuana marketing effort, after all, is worth drawing the attention of the Drug Enforcement Agency.

DUIs

Last summer, Colorado lawmakers passed a marijuana DUI rule, setting the legal THC-blood limit for drivers at 5 nanograms per milliliter. The thing is, everyone involved knew the rule made no sense. Unlike with alcohol, marijuana impairment can vary widely from one person to the next. As even the National Highway Traffic and Safety Administration concedes, “It is difficult to establish a relationship between a person’s THC blood or plasma concentration and performance impairing effects. Concentrations of parent drug and metabolite are very dependent on pattern of use as well as dose.” As William Breathes, the venerable pot critic at the Denver alt-weekly Westword, has demonstrated, long-standing marijuana users can refrain from using marijuana for much of a day and still have THC levels several times over the 5-nanogram limit. Plus there’s the fact that there’s little consistency in marijuana dosing—how much THC are you getting from that hand-rolled joint or those two bites of pot brownie? Yes, intoxication is always a bit of a guessing game with alcohol, too—but it’s far more of a guessing game with weed.

Still, with the world and the feds watching, Colorado had to demonstrate it was taking stoned driving seriously; hence the need for the marijuana DUI law. But lawmakers hedged their bets by making it a “permissible inference measure,” meaning it comes with a potential get-out-of-jail-free card. Getting caught driving over the 5-nanogram limit means you’re presumed to be guilty, but you’re allowed to argue in court that you weren’t impaired. (Washington state’s 5-nanogram limit, on the other hand, is a “per-se measure,” meaning you have no defense if you’re busted over the limit.)

Is Colorado’s marijuana DUI rule flawless? Far from it. But as the state’s policymakers have come to realize, the world’s first legal pot rules aren’t going to be perfect. They just have to be good enough. Good enough to keep the feds away, good enough to keep marijuana stakeholders happy, good enough to keep Coloradans from worrying they’ve made a horrible mistake. Is Colorado’s regulated pot system good enough? In the coming weeks, we’re going to find out.

Next up: Who’s watching the pot? How do you keep track of the state’s 677,000 legitimate marijuana plants from seed to sale, to ensure none of it ends up on the black market?