ANGELES—I didn’t come to the Balibago district of Angeles city for the hostess clubs, or the girlfriend karaoke, or the “fun balls” they’re selling at the hotel bar. If I’m staying the night in the sex-tourism capital of the Philippines, if my deluxe suite has a ruby-tinted bulb above the mattress, if a strange woman keeps pawing at my nice hair, nice hair—well, that’s just part of the tour.

There’s a mountain a few miles outside the city. It’s been there forever, but most locals didn’t know it had a name until 20 years ago. Then one morning in June 1991, a black cauliflower of pumice ash blossomed from its summit, spraying clouds of dust over the whorehouses of Balibago and beyond. When the explosions subsided, more than 17 million tons of material had been launched from Mount Pinatubo, sending a black fog across a million square miles of Southeast Asia. The largest volcanic eruption in almost a century left behind a sulfuric veil that scattered daylight and sprinkled sunsets around the globe with apricot and violet. Three years later, the whole planet had cooled by nearly a full degree.

Pintatubo—or rather, the Gomorrhan city of 300,000 that sits in its shadow—marks the first stop on my brimstone tour of the Philippines. I’ve come to a country smack in the middle of the Pacific Ring of Fire, a 25,000-mile tectonic horseshoe that’s home to nearly two-thirds of the world’s active volcanoes, so I can see these geological powder kegs up close.

Most natural hazards hide out in the ether. They’re globs of energy in offshore weather patterns or dangers that quiver in dry twigs. But in the Philippines, active volcanoes sit right there on the skyline, like a battery of cannons a mile high that could go off at any moment. I’m here to find out what it means to have life’s uncertainty made concrete. I’m here for the mountains and the lava.

***

As luck would have it, I find the source of the Pinatubo eruption on my first night in town. Her name is Helen, and she’s got a steady face that looks like it’s been fired in a kiln. I watch her peel a mango in long, even strips.

Photograph by Matt Elkind for Slate.

“What a night of lovemaking,” says her boyfriend, Philander Rodman, Jr., a towering U.S. Air Force veteran in his early 70s. “You want to see Pinatubo? That’s Pinatubo right there.”

We’re sitting in a tin-roofed, open-air bar that’s about a mile from my hotel. It’s walking distance, if you don’t mind the grubby backstreets of Balibago, where nightclubs rub up against each other in twosomes and threesomes. There’s the Screw Shack and the Thi-Hi, the After School and the Nasty Duck. By the time I find Philander’s joint, I’m ready to stop anywhere that isn’t running a wet T-shirt contest.

The name of the bar—Rodman’s Rainbow Obama Burger—is spelled out in Pan-African colors across a wall mural, next to an old motorcycle. Philander sits in a plastic chair, stroking a kitten that appears to be chained to a bookshelf. A vintage jukebox plays “Purple Rain.”

I’ve ordered a cheeseburger, and it comes out limp and defrosted on a piece of bread stained in swirls of yellow, red, and green food coloring. I take a few bites before I get the reference: Philander’s “rainbow burgers” are an homage to Dennis Rodman, the basketball player who spent 14 years on the Pistons, Spurs, and Bulls. At the peak of his career in the mid-1990s, Rodman adopted a psychedelic hairdo that looked something like the top half of a multicolored hamburger bun. There’s a photo of the All-Star forward on the wall for reference, hanging behind a string of Christmas lights.

Did Philander Rodman know that Dennis Rodman had just been inducted into the basketball Hall of Fame? Of course he did. He’s the proudest father you’ll ever meet.

Photograph by Matt Elkind for Slate.

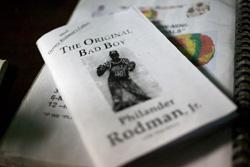

I haven’t been in the bar five minutes when Philander sets out a stack of homemade booklets in plastic sleeves. On top is his “Rodman Family Calendar,” decorated with an image of Dennis flying through the air for a rebound, next to one of Philander in a Bulls replica jersey. In real life, the two men haven’t been in the same room since the mid-1960s, when Philander left his wife and 3-year-old son in New Jersey and disappeared halfway around the world.

For several hours, and several beers, the long-lost son is all we talk about. Philander is a few inches shorter than Dennis and says he’s never played basketball. Still, he looks like he’s been genetically engineered to grab rebounds. His arms are like fruit-pickers: When he reaches out to say hello, it’s like I’m shaking hands with Mr. Fantastic.

“I didn’t leave Dennis; I left his mom,” Philander tells me. Either way, losing his son—and his son’s money—seems to have produced a deep wellspring of regret, and a single-minded determination to cash in. He gives me a self-published Tagalog-language phrasebook and signs the inside page: “To: Dan. From: Dennis Rodman’s father living in the Philippines.” Just below his signature, he adds a postscript: “Don’t forget: Leaves never fall too far from the trees that they fell from.”

Philander has moved on in other ways, though. Since the breakup of his first marriage, Dennis Rodman’s father in the Philippines has taken three more wives and produced another 28 children.

He’s eager to brag: Did I know that one of his kids is seven feet tall? That half a dozen have played professional basketball? When I test him on the kids’ names, though, Philander gets bashful. There are a lot of them. In the end we refer to a numbered list in the Rodman Family Calendar. Four children—Nos. 16, 17, 23, and 29—are also named Philander, and another four are named Phil or Philip. But my eye catches the name of a girl born here in Angeles on June 22, 1991, a week to the day after the explosions at Pinatubo. Pina Marie—that one he remembers. He named her after the volcano.

***

Here’s how Philander Rodman begins the 29th chapter of his unpublished memoir: “The devastating eruption of Mt. Pinatubo on June 15, 1991 didn’t stop the girls from giving it up.”

Photograph by Matt Elkind for Slate.

If I came here to find out what it’s like to live in the shadow of a volcano, then Philander’s manuscript, laid out in bold all-caps across several hundred pages in an outdated version of Microsoft Word, gives a certain kind of answer.

His wife Celsa was nine months pregnant that summer, and his other wife, Paz, was caring for the kids. Or at least her share of the kids. At 4 a.m. on the day of the eruption, Philander was out on his first date with Helen. She had hair down to her butt, he writes, and the kind of waist that made her ass look bigger than it really was. “This one night, my love came down on me.”

As the volcano started to burble and spew, Philander and Helen made love. Then they took a shower and made love again, and after lying around for a bit, they made love one more time. At daybreak, he handed her a wad of bills, and when she wouldn’t accept it, they had an argument. Philander reminded her that he “never takes free pussy.”

Then he stepped outside, leaving Helen naked on the hotel bed, and found himself staring up at a mushroom cloud. Rocks and sand were turning in the air—“beautiful, but disastrous without my knowing,” as he puts it—and a few minutes later, warm, white ash began to fall from the sky. “I know Helen was good,” Philander thought, “but I didn’t think she could set off a volcano.” When he got back to his bar, everything went dark—so dark that he couldn’t even see Celsa sitting next to him. “That’s no bullshit,” he says, “it was just that black and dark.”

***

The morning after our night of rainbow burgers and cheap beer, my photographer Matt and I are climbing through a silvery-gray ravine edged with ferns and palm trees. A rivulet of yellow slime keeps oozing across our path and off into the rubble. It reminds me of uni.

Our guide hikes ahead in silence. He’s an Aeta—a member of the native tribe that’s been living on the slopes of Pinatubo for at least a millennium. We pass families of tiny, curly-haired people standing in rags beside reed huts. Even their dogs are small. When the conquistadores arrived in the 16th century, they called these tribesmen negritos. Philander Rodman calls them “those little black guys.”

Photograph by Arlan Naeg/Getty Images.

Twenty years ago, this land was green and fertile, and no one gave much thought to the dormant volcano above. Scientists say it hadn’t been active in 600 years, since before the Spaniards landed on Luzon and ancient lava floes had enriched the mountainside with nutrients and made it an attractive place to live. Like a floodplain that beckons farmers with rich soil and then washes them away, a volcano lives in a natural cycle of fertilization and destruction—softening its slopes between rains of fire.

The eruption, when it finally came, was a surprise to everyone. Or almost everyone: Many years earlier, an Aeta storyteller had given a stark warning about Pinatubo, but his message remained hidden until a few years ago. (The typescript, discovered on dusty microfilm at the University of the Philippines, was first published in the Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, and cited in Clive Oppenheimer’s book, Eruptions That Shook the World.) Recorded in 1915, it describes a fearsome, fire-breathing turtle that retreated up the mountain after fighting with another mythical creature. For three days, the turtle burrowed into the summit, shaking the earth and spraying pieces of rock, mud, and ash with a deafening roar. “Now you do not see smoke coming out of the Pinatubo mountain,” the storyteller concludes, “and many believe that the terrible monster is already dead; but I think that he is just resting after his exertions, and that someday he will surely come out of his hiding place again.”

Photograph by Matt Elkind for Slate.

When the Gamera monster re-emerged in 1991, hundreds of thousands of Filipinos were uprooted from their homes. But none were as affected as the 10,000 Aetas who lived closest to the summit. In the days that followed, they were moved from one evacuation center to another, crammed into group tents where hundreds died from measles, diarrhea, and pneumonia.

Now some work as tour guides, taking people like me and Matt on what’s touted as an extreme trekking adventure to the crater. In fact, scientists say there’s no danger of another Pinatubo eruption any time soon, and our adventure tour consists of little more than a bumpy, three-hour drive through a field of rocks, followed by a one-hour hike. When the toxic landscape finally gives way, the view is spectacular: The fiery crater has become a serene mountain lake, tucked between sloping walls of green, with birds flying to and fro. A handful of people swim and laugh near the volcano shore.

***

Back in our hotel, I return to Philander’s memoir. It goes on and on. Having just made love to Helen, and then discovered a mushroom cloud raining ash over Angeles, he thought of his wives and kids. Each family would need a box of groceries—noodles, tuna fish, milk, sugar, coffee. And to each set of provisions he’d add a piece of rope: If you have to evacuate, he told Paz first and then Celsa, tie yourself to the children so no one gets separated.

Photograph by Matt Elkind for Slate.

The pitch-black skies that followed the first blanket of ash lasted through the early afternoon. When the darkness lifted, they all heard a rattling sound coming from up above—it was raining rocks. Then came some more ash, and after that a typhoon. Rooftops that were already piled high with debris now sagged under wet mush. Philander had already sent the kids upstairs with brooms to sweep away the debris as it fell. Others hadn’t been so careful: More than 120 buildings, some of them occupied, caved in at Clark Air Base and the naval base in Subic Bay.

Meanwhile, the roads leading out of Angeles were clogged with traffic and Philander holed up with his buddies for days, drinking and whoring and fussing over the lack of ice-cold beers. Outside, crowds of Filipinos were sifting through the debris—a rumor went around that Pinatubo had spit out a cache of diamonds and now they were scattered in the streets.

Inside the bar, it was “pussy galore.” Philander slept with Helen again—“and again it was ‘gooodddd’ “—and then a few days after that, while the streets were still covered with white ash, Celsa gave birth to their baby girl. Pina Marie is still his favorite, he says, of all the kids with Celsa.

***

Before I leave town, Philander gives me a copy of his memoir on a CD-ROM wrapped in a plastic bag. He’s hoping I can find him a book deal in New York City, like the one Dennis got for his memoir, As Bad As I Wanna Be, which spent four and a half months on the best-seller list in 1996. Philander’s book will be called As Dad As I Wanna Be.

The book is both repulsive and charming, and hard to put down. Still, I get the feeling that Pinatubo will explode again before Philander Rodman is a best-selling author. That’s too bad. Philander’s military pension doesn’t look to be going very far. For one thing, he’s nearly blind; his eyes are foggy and gray. Surgery might help, he tells me, but he can’t afford it.

The bar isn’t bringing in much cash, either. Only two people other than Philander and his girlfriend Helen show up while I’m there. One is Cindy, a chatty Filipina waitress with a lazy eye. Philander’s only patron, so far as I can tell, is Doc—another ex-military man, who arrived in the Philippines in 1977 and gives the impression of having spent every night since at Rodman’s Rainbow.

It’s been a decade since the biggest volcanic event in recent history, and now Angeles itself seems to have gone dormant. The U.S. military pulled out after the eruption, and the city’s sex tourism was never the same. “It used to be all GIs,” Philander tells me. “When the mayor pushed prostitution out of Manila, all the Europeans and Australians came up and ruined the scene.” Asian investors are another source of pique. (I find street graffiti that says “Koreans go home.”)

Yet there’s a sense of ease in Philander’s broad smile. In spite of everything he gives off the air of a contented man. Helen stands beside him with a hand on his shoulder, and his pup—a pit-bull named Chocolatey—nuzzles his leg. When he lifts one of his long fingers, Cindy fetches him another beer. Right here in the bar they look like a family, and one he doesn’t plan on leaving.