Rumors that the Vatican is filled with perverse artworks are as old as the palace itself. Most of the stories are fabrications. But one is not: In 1516, the Renaissance master Raphael decorated a bathroom within the Papal Apartments with erotic frescos. Today, the wicked gallery is called the Stufetta della Bibbiena, the “small heated room of Cardinal Bibbiena,” after the worldly official who commissioned the work. It was, of course, a different era, when Bibbiena, like most papal officials, was a patron of the arts more than a servant of God. He was also the author of risqué plays and an erudite man-about-town. Like his peers, Bibbiena was entranced by the ribald pagan imagery that was being unearthed in Imperial Roman ruins. He asked his friend Raphael to decorate his lodgings in the fashionable classical style, complete with naked nymphs being spied upon by lusting satyrs, with no anatomical detail hidden.

Subsequent residents of the Vatican Palace were unimpressed. The Stufetta has been defaced, whitewashed over, and even turned into a kitchen before a Catholic art expert rediscovered it in the mid-19th century. But access remained limited, to say the least—largely because, after 1870, this section of the palace was turned into the pope’s own residence, and Cardinal Bibbiena’s ancient bedroom was used for official diplomatic meetings with visiting heads of state. Stories of the restored bathroom filtered out amongst the cognoscenti, but only the rarest visitor was permitted a viewing.

It was my greatest challenge.

I sent out emails to every department in the Vatican I could think of, trying to find out who might grant me a viewing. I asked Italian art academics. I quizzed Dr. Giovanni Maria Vian, erudite editor of L’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper. I presented myself to the Secretary of State as a scholar studying “the pagan influence on Renaissance art” —which, of course, was quite true.

And then, out of the blue, I received two conflicting emails. When I opened the first, I gave a shout for joy: It was from the State Secretariat, giving me an appointment to visit the Stufetta the following Monday at 4.30 p.m. “I hope you enjoy the visit,” it concluded amiably. The second informed me in no uncertain terms that the Stufetta was closed to outsiders. End of story.

I decided to print out the first email and turn up anyway.

But there were even more complications. On the day of my appointment, I received another email at 1 p.m. saying the visit was canceled, with no reason given. I shot back begging for a rescheduling. At 2 p.m., a monsignor telephoned me to say, va bene, the visit is on again. Apparently an Italian Minister was scheduled to meet the pope in his audience room. But if I turned up on time, they could slip me into the bathroom just beforehand during a 10-minute window.

By the time I turned up at the Vatican gates, I was a nervous wreck.

This time, the officials who grant entry permits at Checkpoint Charlie were perplexed, since they’d never even heard of the Stufetta. Who was I to be going into the Papal Apartments, the inner sanctum of the Catholic world? I sweated in a corner as calls were made, conversations carried out in hushed tones. The ancient clock ticked. Luckily I had noted down the name of the monsignor who had telephoned me that afternoon, the only human contact in the whole bureaucratic process. He confirmed my unlikely story. I was handed a different, magnificently embossed pass and told to hurry to a far courtyard.

From here, the visit unfolded in a dreamlike pace, as I was ushered into ever more obscure realms of the Vatican. I was escorted into a mahogany-paneled elevator, which rumbled upward into the Papal Apartments. At the top floor, the doors ground open to reveal two halberd-bearing Swiss Guards in their ceremonial plumage of orange and blue, who escorted me along a magnificent sun-filled corridor. On one side were giant picture windows with a sweeping view over Rome. On the other loomed giant antique maps of the world, with caravelles on the waves and the most of the Americas still missing.

After cooling my heels in a waiting room—repeating in my head all the learned observations I would make about “the pagan influence on Renaissance art” —the door suddenly opened and in strode Monsignor Peter Wells, one of the top figures in the secretariat. He is originally from Tulsa, Okla. “Real sorry about the mix-up on times today,” he said. “Hopefully we can get you in and out in a few minutes.”

We passed through Bibbiena’s original bedroom, now a sanitized meeting room, and stopped in front of a small wooden door. Poised with the key, the monsignor was momentarily perplexed. “We open up the Stufetta very rarely. Almost never.”

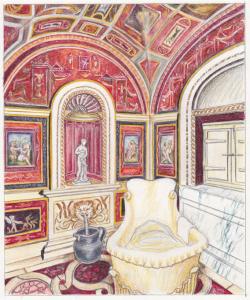

But then we were inside. That tight, vaulted room—twice as high as its 8-foot width—was covered with cavorting naked deities. Raphael had designed his frescoed panels like a graphic novel, recounting the adventures of Venus, the goddess of love, and Cupid, the god of erotic desire, for Cardinal Bibbiena to admire as he lounged in his hot tub. At knee level, the original silver faucet was crafted into the face of a leering satyr. One panel showed the naked goddess stepping daintily stepped into her foam-fringed shell. In others, she admires herself in a mirror, lounges between Adonis’ legs and swims in sensual abandon. A couple of the frames, even more risqué, have been destroyed. One, recorded by an early visitor, showed Vulcan attempting to rape Minerva.

Embarrassingly, I had to ask the monsignor to stand aside, so I could get a proper view of the most notorious image, of the randy goat-god Pan leaping from the bushes with a monstrous erection. I was shocked to see that the image had been vandalized. Someone had etched out Pan’s manhood and filled in the gap with white paint. This, of course, made the object even larger and more noticeable—another parable about the futility of censorship.

Soon I was back outside, heading for the exit. I was so elated, I felt like high-fiving the Swiss Guards at the gates. I’d beheld the fabled Stufetta and lived to tell about it. The images hardly qualified as jaw-dropping porn, but erotica is all about context. To find them buried deep in the Vatican, still surviving the centuries of guilt and repression, gave them a charge no click of the mouse could ever achieve.

To this day, I’m still not too sure why they let me in. Over pasta and wine a few days later, my Vatican correspondent friends suggested it was part of a grander plan. “They must have decided it was better to show you the Stufetta than keep you out,” said one old hand. Sometimes even the Vatican has to confess, and maybe I was the right candidate for the job.

As it says in the gospel of Luke: “For nothing is hidden that will not be made manifest, nor is anything secret that will not be known and come to light.” It may take a few centuries longer than expected, but the Vatican is on a different clock than you and I.