Malta: 10 Days, 6,000 Years of History

Early one morning, we made our way to Malta's National Museum of Fine Arts in Valletta. Though the tourists were already out and about in the city streets, we had the museum to ourselves. Our fellow sightseers weren't wrong to skip the museum; its collection is small and unremarkable. And yet it reveals something essential about Malta and its tourism industry.

Take, for instance, one of the museum's prize possessions: a watercolor of Malta's Grand Harbor, painted in 1830 by J.M.W. Turner. (Actually, the painting belongs to HSBC, which loans it to the museum.) It's not just that this is a work by a foreigner hailing from a colonial power. Turner never even bothered to visit Malta; he saved himself the trip and based his scene on a work by another painter. The painting itself is diminutive, about the size of a sheet of office paper. It was commissioned as the basis for an engraving for a book recounting the travels of Lord Byron, who visited Malta in 1809 and 1811—and doesn't seem to have much enjoyed his stays. (The game-legged poet pouted when the island failed to honor his arrival with a salute from her guns and complained about Valletta's steep streets.) A painting by a Brit who never visited Malta commemorating the journeys of a Brit who did visit but perhaps wished that he hadn't—that's a funny national treasure.

At first, the museum's evident enthusiasm for the Turner struck us as somewhat sad. Come on, Malta, have some respect for yourself: If Turner couldn't be bothered to come see the lovely view of Grand Harbor for himself, fold the little thing up, buy a stamp from the Knights of St. John, and send it back to Jolly Old England. But the more time we spent on the island, the more we came to appreciate the willingness of the Maltese to tout the country's brushes with history, regardless of the light they cast on the island or its people. In the last two decades, Malta has revived a moribund economy by putting all its eggs in the tourism basket and not worrying too much about what each attraction might say about the island were a tourist to stop and think about it for a moment. If you've got a Turner, flaunt your Turner.

Still, we couldn't help noticing, to our growing amusement, just how many of Malta's tourist draws celebrate visits by people who arrived here either by accident or under duress—and didn't stick around very long. Two of Malta's great cathedrals are dedicated to St. Paul, who is said to have shipwrecked on Malta. (After a short stay, he continued on to Rome, where Christian tradition holds that he was beheaded.) The island's most impressive catacombs are said to have been the hiding place of St. Agatha, who fled to Malta to avoid the persecution of Christians in her native Sicily. (After a short stay, she returned to Italy, where her breasts were cut off.)

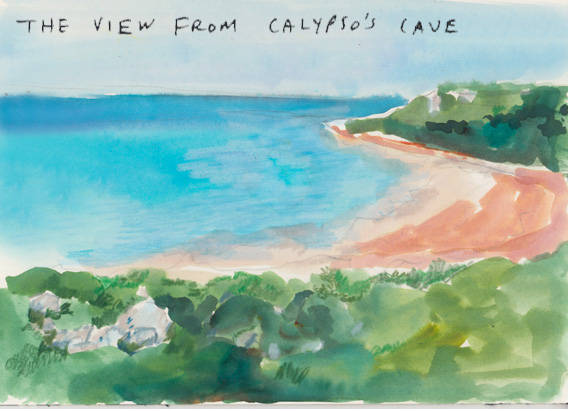

Gozo, Malta's sister island, has long claimed to be Ogygia, the island on which Odysseus is waylaid by the nymph Calypso in the Odyssey. Calypso offers the Greek hero eternal life, eternal home-cooked ambrosia, and eternal nookie in her seaside grotto. But he longs for Ithaca and decides instead to risk a long journey on angry seas to get there. "Calpyso's Cave" pops up in all the guide books, but it, too, is a strange place to brag about: Come, see the spot where not even the promise of immortality could persuade a man to put down roots on the Maltese isles. The cave itself turns out to be little more than a dank hole with a great view of the Mediterranean, guarded by a ramshackle postcard stand. A small sign offers an unsatisfactory account of how this particular cave came to be associated with Homer's epic, though Byron, at least, seems to have bought it. He invokes the myth in the second canto of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage:

But not in silence pass Calypso's isles,

The sister tenants of the middle deep;

There for the weary still a Haven smiles,

Though the fair goddess long hath ceased to weep,

And o'er her cliffs a fruitless watch to keep

For him who dared prefer a mortal bride.

If only the nymph had been more patient, her watch would have born fruit. Odysseus did eventually return to Malta, in 2003, in the person of Sean Bean. Bean played the wiliest of Greeks in Troy, which, like several of Hollywood's sword-and-sandal epics, was filmed on Malta.

One of Malta's most compelling tourist attractions is the work of one of its unhappiest visitors. Walking through the National Museum of Fine Arts, we quickly noticed that the walls were lined with art by Italians who painted in the style of their countryman Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. The paintings are largely unimpressive, but staring at the work of a bunch of Caravaggisti is a great way of warming up to see the master himself, whose "Beheading of St. John" and portrait of St. Jerome reside a few blocks away at the Co-Cathedral of St. John. You don't need to be an art historian or gallery denizen to see that Caravaggio's imitators never figured out his theatrical use of light, or his knack for treating heavenly subjects with an unsettling, earthly frankness. In Caravaggio's treatment, the beheading of St. John is a brutal but utterly mundane affair—the executioner seems to be having trouble working a blade through the saint's neck; two ruffians leer at the scene through barred windows. There's not a cherub to be found.

Caravaggio arrived on Malta in 1607, and not because he'd read about the good snorkeling. The previous year, the volatile painter had killed a man in a swordfight in Rome, possibly over a tennis match. (The exact nature of the dispute is itself disputed—it's not clear whether the painter took part in the match, merely had a betting interest in its outcome, or, as Andrew Graham-Dixon argues in his forthcoming book on Caravaggio, whether the fight over tennis had been invented to cover up an illegal duel between the two men.) He came to Malta with the idea of joining the Knights of St. John, perhaps in the hope that dedicating himself to the order would expiate his mortal sin.

Getting a common murderer, even one as talented as Caravaggio, admitted to the noble order took some doing. But Alof de Wignacourt, the incumbent grand master, recognized Caravaggio's talent and the benefit of having him beholden to the knights. (And to himself: One of the first paintings Caravaggio completed on Malta was a portrait of Wignacourt, which now resides in the Louvre.) The grand master successfully lobbied the pope on the painter's behalf, and Caravaggio returned the favor by painting several masterpieces in a short span. Among these are a portrait of St. Jerome and "The Beheading of St. John," which hangs in the oratory of the Co-Cathedral of St. John. Caravaggio seems to have been especially proud of the latter—he scrawled his name in the blood dripping from the baptist's half-severed neck, the only time the painter ever signed one of his works.

It was in this same oratory, barely a year after Caravaggio arrived on the island, that his tenure on Malta came to an unhappy end. On Dec. 1, 1608, the Knights of St. John gathered under the recently completed painting of the beheading and expelled Caravaggio from their order. Their new brother had taken part in the brutal beating of a fellow knight, a serious offence even if the recipient of the beating had foot faulted. Caravaggio was defrocked in absentia. Though he'd been apprehended after the fight and placed in Malta's most forbidding prison, he promptly escaped—no one knows how. He made his way back to Italy, where he'd be dead by the summer of 1610.

***

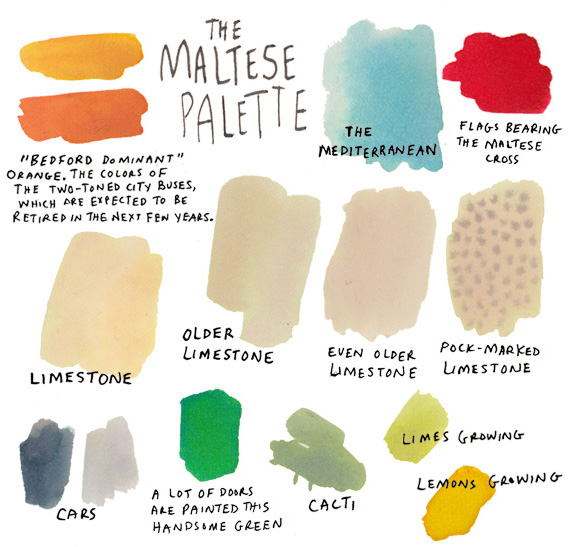

With all due respect to Odysseus, Byron, and Caravaggio, we left Malta thinking they hadn't given the island a fair shake. It's not always the most welcoming place. As you might expect of a nation that has been dominated by a parade of foreign powers over the course of several millennia, it greets visitors indifferently. The Maltese aren't rude, exactly, just a bit brusque—buses don't stop for passengers to disembark, they slow to a roll, and they make no allowances for tentative sightseers who aren't sure this is their stop. The Maltese seem confident you'll figure it out eventually, and you do. The island's great historical, artistic, and natural treasures beckon.

On our last night on the island, we attended a free concert at Valletta's majestic old music hall, Teatru Manoel. An orchestra was in from Rotterdam, performing works by Dmitri Shostakovich. We enjoyed a concerto for piano, trumpet, and strings, then ducked out at intermission to get a jump on dinner at a nearby restaurant. As our entrees were arriving, a Maltese couple who had also attended the concert but stayed through to the end sat down at the table next to us. Seeing the concert program on our table and the plates of rabbit already before us, they shot us an unmistakably reproving look: You couldn't be bothered to stay for the whole show? We were at once shamed and charmed by their frankness and evident outrage on behalf of the out-of-town musicians, the theater's Maltese patrons, perhaps even the long-dead Russian composer. The next time we visit, we'll stay for the grand finale.