Aymann Ismail

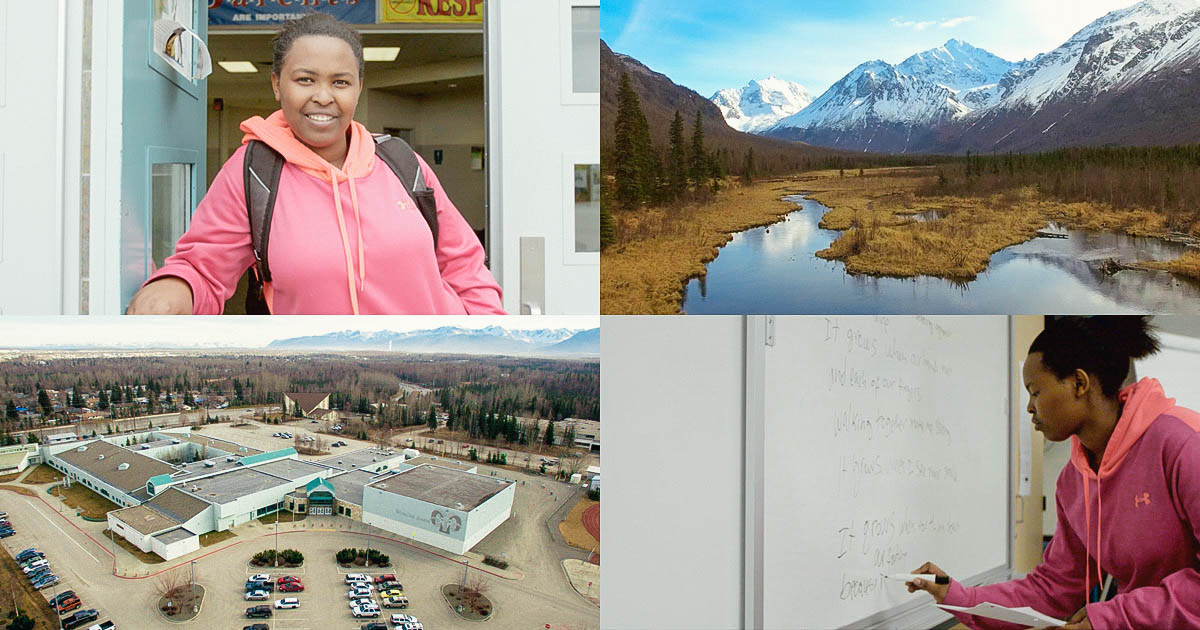

ANCHORAGE, ALASKA—Until the summer of 2014, 16-year-old Florence Mbabazi had spent all of her short life in northern Rwanda’s Gihembe Refugee Camp, a humming sprawl of more than 3,000 mud houses with sheet metal roofs. Her parents, who had been farmers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, fled to the camp in 1997 after civil war tore apart their country. Florence didn’t love all the rules at the camp’s school—students had to wear uniforms, and even the girls had to shave their heads—but she was mostly happy. At least there were always things to do.

When word finally came in September 2014 that after 17 years, Florence, her mother, and her five siblings would finally leave the camp for the United States, she imagined the bustle, skyscrapers, and glamour of New York City. When she learned she would be moving to Anchorage, Alaska, she cried.

But Anchorage had something to offer Florence that even New York City does not: one of the country’s strongest education programs for refugee students. In Anchorage, middle and high school students like Florence and her younger sister, Denise Bamurange, spend half their day at a program called the Newcomers’ Center with other new arrivals who speak little to no English. They spend the rest of the day at neighborhood schools, fully immersed with the general student population.

Aymann Ismail

Aymann Ismail

By adopting this rare, hybrid approach, the Newcomers’ Center does something relatively unique in the world of English language and refugee education. In some communities, like Atlanta, refugee students get thrown in the general student population immediately, where they often struggle with the language and American social and cultural norms. In others, including parts of Maryland and New York, they’re isolated from native-English speaking peers for most or all of the school day—and sometimes fail to ever truly adapt to the American classroom.

“Anchorage seems to be doing it right,” says Rebecca Callahan, an English language education professor at the University of Texas. A hybrid structure, she argues, lets new arrivals get comfortable with English and America in a safe space, then test out what they’ve have learned at their neighborhood schools.

“Second-language education is large and complex, but then you add the refugee layer and you have psychological trauma and often interrupted schooling,” Callahan says. She says an integration program is especially important and powerful for refugee students, who find it comforting to have friends who’ve experienced similar traumas but who need to be efficiently immersed in their new country’s language in order to progress.

Alaska and its largest city may not be regarded as particularly diverse places, but over the past decade, the Anchorage School District has become one of the most diverse in the country, serving students who speak nearly 100 different languages. Out of 48,000 students, almost 6,000 qualify for English language learner services, though only a small handful need the type of intense programming the city’s immersion program provides. Students at the Newcomers’ Center come from countries as varied as Somalia and South Korea and speak languages as obscure as Triqui and Mandinka. And as more and more school districts across the country grapple with the question of how to best integrate and educate students from a vast array of cultural and linguistic backgrounds—including ones whose families are fleeing discord and violence—Anchorage and the Newcomers’ Center offer a fascinating, if imperfect, case study in how to help these students acclimate with sensitivity and success.

Those lessons will become especially acute in coming years. Secretary of State John Kerry said in January that the United States would take in thousands more Central Americans fleeing violence, almost all of whom are children. This is on top of a plan announced last fall by the Obama administration to increase the number of refugees admitted to the United States this year by 15,000, to 85,000. In 2017, the U.S. will admit at least 100,000 international refugees. Almost half of those are likely to be children. And they’ll have to go to school somewhere.

* * *

Aymann Ismail

Aymann Ismail

About 130 refugees arrive in Anchorage every year. That’s not a lot compared with major cities in the United States, but it is for a city of slightly more than 300,000. The U.S. Department of State assigns the refugees to Anchorage—the only Alaskan city that accepts them—and Catholic Social Services places them and provides services.

Historically, the majority of the city’s refugees have come from African countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, and Sudan. Anchorage has also welcomed several immigrants from Iraq and Myanmar. And although Alaska hasn’t been assigned any Syrian refugees, Jessica Kovarik, the state refugee coordinator for Catholic Social Services’ Refugee Assistance and Immigration Services program, says that’s likely to change, since the city is well set-up to accommodate Arabic-speaking immigrants. Every year, Alaska also receives several dozen “secondary migrants”—refugees who are sent to other places but move to Anchorage for its steady economy and abundance of jobs in industries like fish processing and tourism.

Anchorage wasn’t always home to such diversity. When the Newcomers’ Center opened in 1996, it served just 11 students—all of whom were Spanish speakers. Today, it has 87 students hailing from more than 20 countries and who speak more than 15 different languages.*

| Language | Speakers | Percent of ELL students |

|---|---|---|

| — | — | — |

| — | — | — |

| — | — | — |

| — | — | — |

| — | — | — |

The center is housed at Wendler Middle School, a one-story building located in northeast Anchorage. The hallways are dotted with anti-bullying and diversity slogans such as “Appreciate everyone and mock no one.” The first day I visited, a 15-year-old named Eliohany Mejia Guzman—just Hany to her friends—who had emigrated from Guatemala about two years ago led my tour. As we walked down the hallway, she stopped to check on a student who had arrived just days earlier.

“He’s new,” Hany told me. “I speak Spanish. He speaks Spanish. So I help him.” During their math class back at their neighborhood school —which, in their case, is also Wendler— she sits next to him, helping to translate and encouraging him to work up the courage to volunteer answers. Teachers say that while such pairings aren’t always intentional, students naturally gravitate toward newer arrivals who share their language, helping them adjust and welcoming them to what is—for most of them—a new and occasionally intimidating environment.

The integration program not only helps the students learn English. It also helps them learn to “do school”—a phrase used often by teacher Bonnie Palach—in America, including instruction in basics such as how and when to change classes throughout the day. While some students have had several years of formal education in their home countries, others arrive unable to read in their native languages and lacking basic math skills. Some students have watched family members die in violent circumstances; others have bounced from refugee camp to refugee camp.

Shirley Greeninger, the refugee liaison for the district, tries in a family’s initial enrollment meeting to gauge the refugees’ education level—something she says is incredibly difficult to predict. Even within individual countries, education opportunities vary tremendously depending on the refugee camp to which the family was assigned. Some camps offer almost no education, while others might have comprehensive schooling through the American equivalent of high school. Because the families are often unable to share many details, Greeninger researches the camps and shows pictures from them to staff members to help them better understand and prepare for each new student.

In addition to educational gaps, the Newcomers’ Center was also founded to help immigrant students who were struggling to adapt to the American school environment, which a 1996 memo on the center’s establishment noted had produced “enormous and serious issues.” While current staff acknowledge that such harsh-sounding language likely stemmed from the minimal diversity in Anchorage before the early ’90s, they believe the Newcomers’ Center still serves a role in helping new students adjust to cultural expectations.

New arrivals may not realize certain behaviors are inappropriate, says Katie Bisson, the immigrant liaison for Anchorage School District. Newcomers’ Center students, especially boys, often stand too close to others, roughhouse in hallways, or touch other students without knowing expectations are different in American schools. She said these conversations are often difficult but are integral in helping the students adjust.

Palach tells me it’s just as much her job to teach students to feel comfortable in American classrooms as it is to teach academic material. “It’s a shock to the system for them,” she says. “If we don’t help them understand how to feel comfortable here, they won’t learn, regardless of how smart they are.”

* * *

Florence Mbabazi began school in Anchorage just two days after she arrived in September 2014. Having spent almost all of her life in the small, simple buildings of the refugee camp, she was overwhelmed by the sheer size of the two-story East High School building, where she started off in a Newcomers’ Center satellite with dozens of other recent arrivals.

Florence and her sister, who is 14, got to swap their school uniforms for jeans, tennis shoes, and colorful T-shirts. They let their hair grow out, at least a little. Florence keeps hers in a short afro while Denise wears long, thick braids.

At first Florence constantly got lost. Other students were eager to help her, but none knew her native Congolese Kinyarwanda, and she spoke very little English. Both sisters are shy, which made them even more reticent to experiment with a new language. But they had come to the right place for drawing out introverted, trepidatious adolescents with little knowledge of English.

From the start, Denise spent half days at the main Newcomers’ Center site, enrolled in Palach’s class—the lowest level of English. Denise was reluctant to speak in the first few weeks, which Palach says is normal. She doesn’t pressure students into talking, instead letting them acclimate with their surroundings while she keeps tabs on their body language and engagement level. Denise “was obviously paying attention, listening, observing, and demonstrating that she was engaged,” says Palach.

To draw her out, Palach used well-practiced strategies. Instead of calling on students directly, she draws names, since it’s a less threatening way for students to know that they’re expected to speak in class. She also seated Denise next to a student who spoke more English and placed her in smaller groups for speaking activities.

After a few months in Anchorage, Florence and Denise’s family moved to a new apartment, and Florence started spending her mornings at West High School and her afternoons at the main Newcomers’ Center site, closer to her sister. Jeffrey Thurston, Florence’s English teacher there, calls her one of the “deepest thinkers” in his class. While Florence knew some English before coming to the United States, Thurston says her grasp of the language has improved even over the course of the year—something he believes is bolstered by her willingness to be an active participant in class both at the Newcomers’ Center and at her home school.

Aymann Ismail

Aymann Ismail

On a drizzly day in early October, Thurston began a history lesson on native peoples in the United States, telling his students it’s “important to understand America’s struggles with inequality happened from the beginning.” The students broke into groups, each working to explain a different piece of native culture. Florence quietly researched irrigation with another student, occasionally consulting a bulky dictionary that sits on her desk. Thurston says even the use of a reference book shows how much progress Florence has already made.

“People think the dictionary is this great thing for English learners, but it’s intimidating,” he says. “You look up a word and then you have to look up three more words just to understand the definition.”

* * *

While Anchorage’s program may provide a national model for success, it faces challenges—mostly of the financial variety.

To help fund its schools, Anchorage relies on oil revenue, which cushioned it from the budget shortfalls felt by school districts across the country a few years ago. But now plummeting oil prices and tax revenues have strained the school district’s finances. For each of the past three years, Anchorage School District faced budget shortfalls of around $20 million, forcing the district to slash jobs and programming.

The Newcomers’ budget is a slim $350,000, not counting the cost of facilities or busing, with a few additional dollars added for supply and textbook upgrades annually. While the center didn’t take any direct hits this school year, the counselors at almost all neighborhood schools who worked directly with Newcomers’ students were laid off, leading to wide variation in the services newly arrived students can expect in their home schools. The district also cut back on training for general education teachers in how to work with students who speak no or little English.

The laid off-counselors had helped the students transition between schools while attending the Newcomers’ Center and into full-time mainstream classes once they left. But now, says district refugee coordinator Greeninger, some parents complain that the transitions aren’t as well-coordinated and their kids sometimes end up taking redundant classes at different sites. “Things just start falling through the cracks,” she says.

These inconsistencies worry Philip Farson, the director of the Anchorage School District’s English Language Learners Program, who says the district currently has no structured way of tracking students when they leave the Newcomers’ Center to spend full days in neighborhood schools. “We don’t want them to be placed into the low and slow classes just because schools don’t understand who they are,” he says. “We hope that’s happening, but we have no way to know.”

Anchorage’s model remains better than many of the alternatives, however. Annie Duguay is the associate director of pre-K–12 English language programs at the Center for Applied Linguistics, a nonprofit that focuses on language and bilingual education. She says immigrant students can become too isolated if they spend their whole school day segregated from other students, for example.

And although Duguay also believes that poor training among teachers in similar programs has been part of the problem nationally, Anchorage seems to have dodged this issue. Although the policy has since changed, none of the current teachers at the Newcomers’ Center were required to have ELL certification when they were hired. Not a problem, says Farson, as all of the teachers have been on the job so long that they’ve learned how to teach the students thanks to years of experience. Thurston, the newest teacher, is in his seventh year at the Newcomers’ Center. Jessica Stern is in her 10th year. And Bonnie Palach has been working as a tutor in the district since the doors of the Newcomers’ Center opened; she started as a classroom teacher 15 years ago.

Even as resources they rely on begin to fray, the Newcomers’ Center’s staff is confident it’s found a method for integrating refugees that simply works. Although teaching there can be “difficult, challenging, frustrating, demanding, and energy-draining,” Palach says, the connections she and her students make with one another are worth the struggle. “Many of my former students are also friends with each other,” she says. “Even after all these years.”

Aymann Ismail

Aymann Ismail

* * *

In her second year at the Newcomers’ Center, Denise Bamurange’s English has improved tremendously, so she’s moved up to Jessica Stern’s frenzied yet warm middle-level English class. One fall morning, the students quietly slurped juice boxes and ate cereal while Stern readied an assignment on editing symbols that the students would use to fix letters they’d written to their families.

Denise tentatively volunteered to read the first example, raising her hand with a nervous smile. “She is are happy,” read Denise, giggling at the mistake, and then instructed the class to put a slash through “are.”

Denise breezed through the letter-writing assignment—writing two of them by the end. While the rest of the class marked up their letters with Xs and slashes, Denise gasped at her only mistake—an incorrect capitalization. Hany, the friendly Guatemalan student, wrote a letter that listed Denise as one of her many friends.

The rest of the family has been settling in as well. The girls’ father died years ago at the refugee camp. But with the help of Catholic Social Services, both their mother, Felicite Nyiratebuka, and older brother, Hambifura Ndayikunda, found jobs. The mother, who speaks very little English, works at a gym cleaning the equipment. She attends classes daily at the local Catholic refugee center, learning English and gaining job skills.

The school district, which makes a point of hiring refugees in order to inspire the students, gave Ndayikunda a job helping special needs adults in a district vocational school. (His family cobbled together enough money to allow him to finish high school and learn English before leaving Rwanda.) He has a second job at night washing dishes in a restaurant.

Next school year, Florence will transition out of the Newcomers’ Center and spend full days at West High School. She feels good about that. “My English is better now, and I think I’ll be OK.” Denise will be in high school next year, and the staff at the Newcomers’ Center is still deciding whether they’ll keep her in the program for an additional semester or allow her to transition to West full-time.

Both Florence and Denise agree that the Newcomers’ Center was integral in helping them feel at home in Alaska. Surrounded by peers with similar struggles and tumultuous backgrounds, they say they felt comfortable making friends and pushing their limits. The Newcomers’ Center gave them their first feeling of community and belonging in a strange new land.

And although Florence was disappointed when she looked at the map two years ago, she now realizes the bustle of a big city would have been too overwhelming. In just a couple of years, she hopes to attend college in the Anchorage area, close to family and to the place she now calls home.

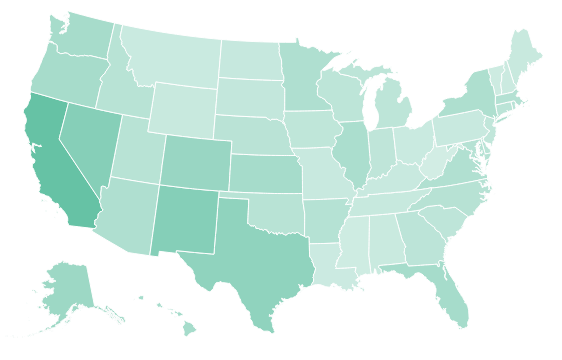

Tomorrow’s Test is a weeklong series looking at the challenges, tensions, and opportunities as the United States shifts to a majority-minority student population in its public schools—a milestone the country as a whole will reach within the next generation. It is a collaboration with the Teacher Project at Columbia Journalism School, a nonprofit education reporting fellowship.

Photography and video by Aymann Ismail.

Correction, June 6, 2016: The interactive map of English language learners in the U.S. originally listed Chinese twice for some locations. The second reference to Chinese should be Haitian. The interactive has been updated. (Return.)