This article is part of the United States of Debt, our third Slate Academy. Join Slate’s Helaine Olen as she explores the reality of owing money in America. To learn more about this project, visit slate.com/Debt.

I spent the entirety of my teens and early 20s on a diet. Every day for more than a decade, I wrote down every item of food that passed through my lips, along with its caloric content. I weighed and measured ingredients to make sure I knew exactly how many calories I was consuming. On the days I ate more than my allotted 1,500 calories—sometimes several times more—I felt out of control and angry at myself. On the days I ate fewer than 1,500 calories, I felt calm, virtuous, and empowered. I thought about food all the time, and I often flipped through cookbooks and food magazines for fun, ogling recipes and calculating whether I could afford those calories.

After years of therapy and feminist indoctrination, I’ve accepted that my body looks the way it looks. I haven’t kept a food log or counted a calorie in years. I am no longer a poster girl for disordered eating. This feels like a huge blessing: I am so much happier now. But my deep-seated drive to quantify and control things has found another outlet: budgeting.

On any given day, I can tell you how much money I have allotted for the rest of the month. (As I write this, it’s $203.84.) That’s because I’ve tracked every penny I’ve spent on one (very long) Excel spreadsheet for the past seven years. Some months I overspend, and my balance dips into the negatives, which makes me feel out of control and angry at myself. Some (far rarer) months I spend less than I’ve allotted, which makes me feel calm, virtuous, and empowered. Now I read personal finance blogs and check my credit card reward balances for fun, calculating when I’ll be able to redeem them.

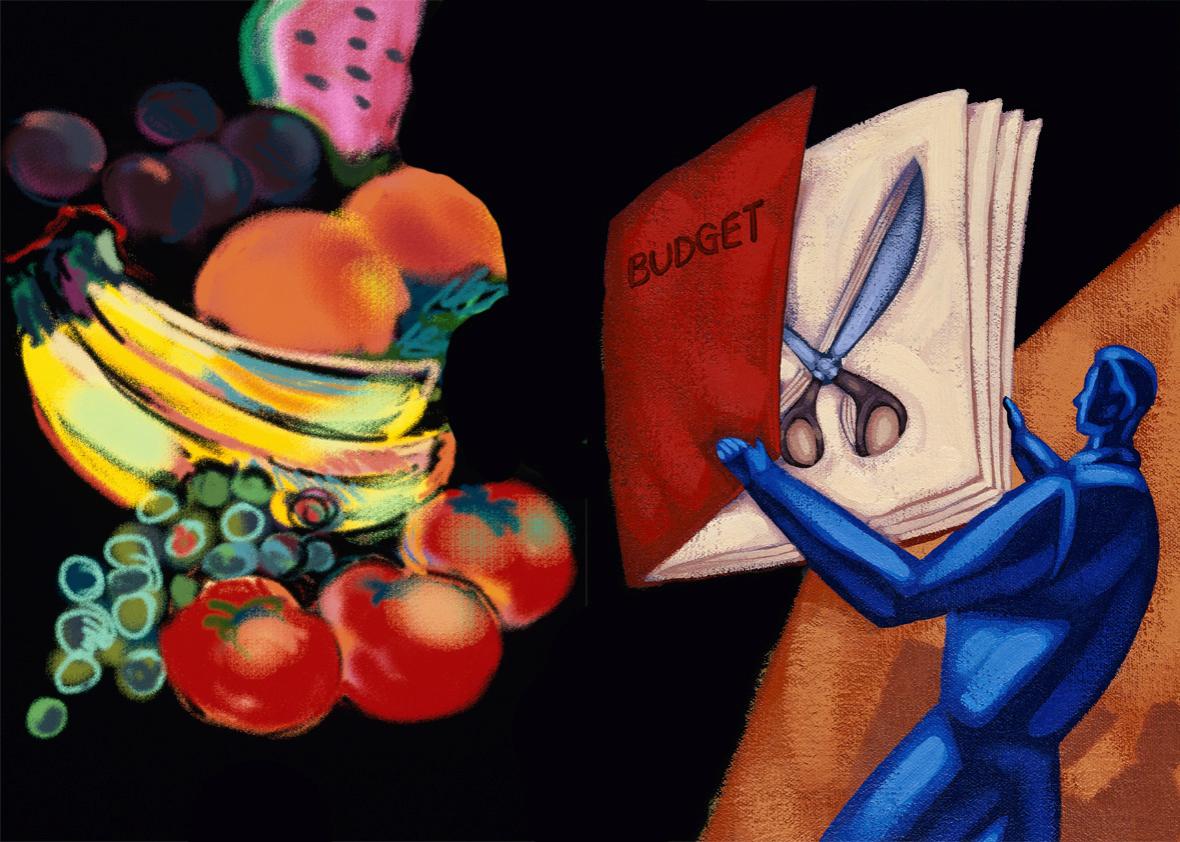

Dieting and budgeting aren’t so different from each other. In both cases, you are restricting an activity that is fun and, to a certain extent, necessary for survival, in the pursuit of some long-term goal. They often involve eliminating entire categories of consumption, whether simple carbohydrates or designer shoes. And they both carry moralistic overtones: We feel good when we follow our diet or budget plan and bad—sinful, even—when we don’t. And they can both devolve into fixations that may or may not be detrimental to one’s mental health. That’s because they’re both a way of trying to exert control over something you’re not actually fully in control of.

It can be hard to see things this way, because our culture insists that weight and finances are personal problems that can be solved by dint of hard work and discipline. People with large bodies are shamed, stigmatized, and labeled as lazy and impulsive. So, too, are people who rack up personal debt. Popular personal finance guru Dave Ramsey, who’s been called out for his particularly severe approach to advice, lists “They are unwilling to sacrifice,” “They’re addicted to stuff,” and “They’re lazy” in his blog post “6 Reasons People Stay in Debt.”

The idea that weight and debt are both within our control is a fantasy. It all largely comes down to luck. Weight and body shape are largely determined by genetics and environment, and once you gain weight, your chances of losing it and keeping it off are minuscule. For a painfully explicit illustration of why it’s so hard to keep weight off, read Gina Kolata’s recent New York Times article on a study showing that contestants on The Biggest Loser—people who had starved themselves and worked out for hours on end to lose dozens or hundreds of pounds—regained most or all of the weight they’d lost because their resting metabolisms had slowed. Their bodies simply refused to stay thin, no matter how hard they worked.

While the reasons behind why it’s hard to stay out of debt aren’t biological, they can feel as intractable. As Slate columnist Helaine Olen has explained before, wages have been stagnant for decades, while the costs of housing, health care, and education have risen. Meanwhile, social mobility has slowed to a crawl, making it highly likely that your earning potential will mirror your parents’ earning potential. These problems can seem abstract, but on a micro level, how much money we make and how much money we spend are not entirely in our control.

Your income depends on your education, the job market in your area, and whether your manager was open to negotiation on the day you accepted the job. A good portion of your spending depends on the local housing market, the cost of health insurance in your area, the interest rate on your student loans. If you manage to save and invest, your returns will depend on, say, the market response after 52 percent of Britons decide they no longer want to belong to the European Union. You cannot change any of these factors by force of will; you can only strive to survive within their confines. And if you can’t? Look forward to Dave Ramsey calling you lazy and unwilling to sacrifice.

So why do so many of us persist in believing that our weight and our finances are what we make of them? Because they’re comforting fictions. Obsessively counting calories made me feel safe: As long as I knew how many calories I’d eaten, I believed that I could mold my body to my will. Even if I consumed thousands more calories than I’d allotted for the day, I could fix the problem by exercising and fasting the next day. I was consumed by what the writer Kate Harding calls “the fantasy of being thin”: the irrational belief that as soon as you lose X pounds, all your other problems will just go away. At the time, striving for thinness felt like an important part of my identity. I couldn’t imagine life without a svelte body as my goal.

In hindsight, my problem was not the fact that I sometimes binged, or the fact that I had fat on my stomach and thighs, but the control itself: the attempt to micromanage a basic human need that would never go away. Once I gave up on trying to control my eating, it became, paradoxically, much easier to control; and once I accepted that my weight was out of my hands, it stabilized.

It would be nice if something similar were to happen with my finances: Maybe if I give up on the idea of controlling my budget, I’ll spend less and save more, just because I’m less preoccupied with money. But for right now, the idea of abandoning my budget spreadsheet makes me feel antsy. Not knowing how much money I have left to spend this month seems almost as unfathomable as not looking at my phone or not looking in the mirror. The idea of giving up obsessive budgeting makes me feel sad, like I am saying goodbye to a friend whom I like—even though she’s a little neurotic and wastes a lot of my time.

I know, on a rational level, that tracking every dime that passes through my bank account is simply a way of distracting myself from all the ways my finances are out of my control: I could get fired or laid off, I could get hit by a car or get cancer, I could get sued, the stocks in my retirement accounts could crash and not recover. But I’d rather not dwell on these possibilities. I’d rather believe—despite my experience with dieting—that if I keep logging my spending and keeping it in check, someday I’ll have enough money, and all my other problems will just go away.