This article supplements Episode 9 of the History of American Slavery, our inaugural Slate Academy. To learn more and to enroll, visit Slate.com/Academy.

Excerpted from Help Me to Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery by Heather Andrea Williams. Published by The University of North Carolina Press.

By the close of the Civil War, decades of separation had scattered blacks all over the South, and manumission and escape had taken some as far north as Canada. A few had also made it to California. Following the war, they used the new black and Republican newspapers to help carry out their search for long-lost family members. They shaped their memories into brief messages that they published, hoping that word would come back to them about the whereabouts of their relatives.

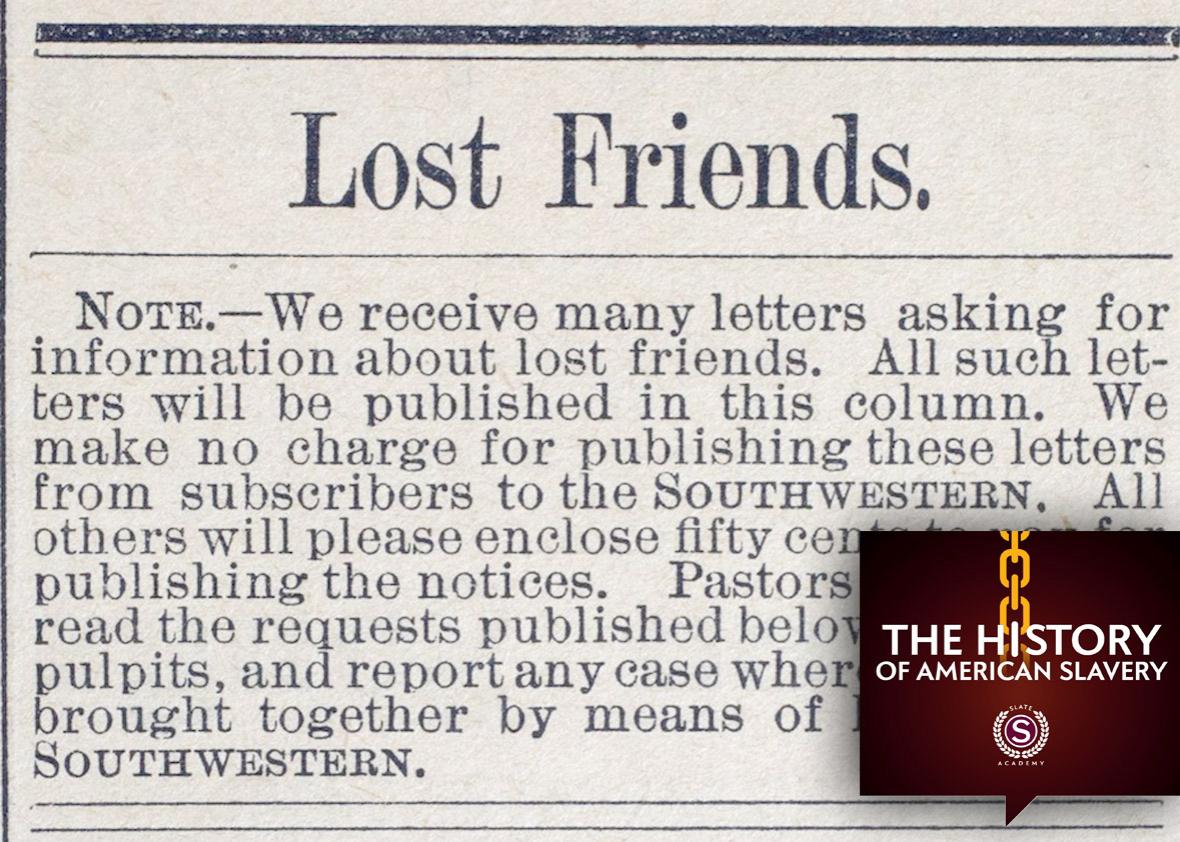

Placing an ad required an expenditure of time, effort, and hope by people who had already invested emotionally by continuing to care about the relatives they had lost. The ads often cost money. In the spring of 1866, the South Carolina Leader invited advertisements with the following notice: “Persons wishing information of their relatives, can have them advertised one month for two dollars and a half.” The Southwestern Christian Advocate included the following notice: “We make no charge for publishing these letters from yearly subscribers. Others will be charged 50 cents.” An annual subscription cost $1.25. Even at 50 cents, placing an ad required a significant monetary investment, as a recently freed person in the South could expect to earn between $5 and $25 per month as a field hand working six days per week. There were exceptions, of course, but most of the black population lived in poverty on the margins of the economy.1

But newspapers provided a public airing of freed people’s memories and hopes and offered the best possibility that many people would read or hear their appeals for information.

To prepare for the search, they scraped together fragments of memory and made judgments about the salience of the information they possessed. They provided names, ages, and physical descriptions of skin color, blemishes, and limps. They enumerated relationships, locations of plantations, points of separation, details about the men and women who had owned them, and names of the men who had traded them — whatever they thought would trigger recognition among readers and listeners. They called out from the newspaper pages to the people who they thought would care and would be able to help.

To encounter the ads as they appeared in the newspapers is to begin to grasp the power and poignancy of these brief, compelling, and urgent dispatches that former slaves used to seek out their loved ones.

Christian Recorder, April 7, 1866

Information wanted of the children of Hagar Outlaw, who went from Wake Forest. Three of them, (their names being Cherry, Viny, and Mills Outlaw) were bought by Abram Hester. Noah Outlaw was taken to Alabama by Joseph Turner Hillsborough. John Outlaw was sold to George Vaughn. Eli Outlaw was sold by Joseph Outlaw. He acted as watchman for old David Outlaw. Thomas Rembry Outlaw was sold in New Orleans by Dr. Outlaw. I live in Raleigh, and I hope they will think enough of their mother to come and look for her, as she is growing old and needs help. She will be glad to see them again at her side. The place is healthy, and they can all do well here. As the hand of time steals over me now so rapidly, I wish to see my dear ones once more clasped to their mother’s heart as in days of yore. Come to the capital of North Carolina, and you will find your mother there, eagerly awaiting her loved ones.

Hugh Outlaw, if you should find any or all of my children, you will do me an incalculable favor by immediately informing them that their mother still lives.

Those who searched well knew that churches provided the spaces in which black people gathered to worship, to learn, and to hold political meetings. It made sense, then, to enlist the help of black ministers and churches, as one newspaper read at a service or a meeting had the potential to reach hundreds of listeners. The Southwestern Christian Advocate included the following message: “Pastors will please read the requests published below from their pulpits, and report any cases where friends are brought together by means of letters in the southwestern.”2 Freed people were not entirely without resources, and they put what they had to work, as the following ad from Kansas Lee illustrates.

Christian Recorder, Aug. 25, 1866

Information wanted

Kansas Lee wishes to learn the whereabouts of her children, four girls and one boy, who were, when last heard from, living in Baltimore, Md. Their names are as follows: Annie, Selia, Sarah, Elizabeth, and Adam Lee. My children were owned by the mother of Benjamin Keene. Address kansas lee Box 507, St. Joseph, Mo.

N.B. Ministers South, who take this paper, will please read the above in their congregations.

Kansas Lee was prepared to have to search broadly, so she asked all ministers in the South to read the ad to their congregations.

The tenuous nature of enslaved people’s public identities did not augur well for the possibility of finding family members. Their births had not been routinely noted and registered. Their sales had not been consistently recorded and archived. Even their names, such an essential signifier of identity, had been unstable. Many functioned with only first names, and even those names were not always permanent. An enslaved person’s name could have changed at the whim of an owner, or due to sale, or to provide cover while escaping, or because a woman had married, or because people took new names once they became free. People who searched sometimes acknowledged these changes, and some acknowledged that they could not be certain of the current name of even the closest relatives.3

Southwestern Christian Advocate, July 17, 1879

Dear Editor: I want to enquire for my father. He went from Franklin Co., Miss. about 1850 to Alabama with a man by the name of Doctor Baker, who was said to be his young master. My father’s name was Milzes Young. I learned that after he left here he went by the name of Milzes Arbet. I now go by the name of Dock Young and am his youngest son. Address me in care of George Torrey, Union Church, Jefferson Co. Miss. Dock Young.

Despite the dispersal of their relatives, some people had doggedly kept track of sales and movements for some time. Amid the turmoil and grief of sale and separation, some enslaved people had also managed to learn the names of the traders who purchased their family members, and they had some sense of where those traders were headed. Rachel Davis, for example, knew of her daughter Abbie’s owners and movements over decades, even including time spent in Cuba. However, she had lost track of her during the Civil War. It must have been painful and frustrating when they lost even a hint of where a child or parent or spouse might be as the sources of information evaporated.

Colored Tennessean (Nashville), Aug. 12, 1865

Of a man by the name of Elias Lowery Mcdermit, who used to belong to Thomas Lyons of Knoxville, East Tennessee. He was sold to a man by the name of Sherman about ten years ago, and I learned some six years ago that he was on a steamboat running between Memphis and New Orleans, and more recently I heard that he was somewhere on the Cumberland river in the Federal army. Any information concerning him will be thankfully received. Address Colored Tennessean, Nashville, Tenn. From his sister who is now living in Knoxville, East Tennessee. Martha Mcdermit

With slavery behind them, a few people who advertised in the Christian Recorder launched rhetorical challenges to the legitimacy of the institution and to those who had thought it justifiable to own and sell other human beings. Their relatives, they said, had “belonged” to, had been the “property” of, or were “claimed” or had been “stolen” by slaveholders. They may have had to keep those critical views to themselves during slavery, but with emancipation, they felt free to publicly sneer at the institution of slavery and those who had claimed ownership of them and their relatives. Doing so would not help in the search, but it likely provided some degree of satisfaction to be able to lash out against those who had brought about their losses.

Colored Tennessean (Nashville), Oct. 14, 1865

information wanted of Caroline Dodson, who was sold from Nashville Nov. 1st 1862 by James Lumsden to Warwick, (a trader then in human beings), who carried her to Atlanta, Georgia, and she was last heard of in the sale pen of Robert Clarke, (human trader in that place), from which she was sold. Any information of her whereabouts will be thankfully received and rewarded by her mother,

Lucinda Lowery,

Box 1121, Nashville, Tenn.

Christian Recorder, April 7, 1866

Information wanted of my children, Lewis, Lizzie, and Kate Mason, whom I last saw in Owensboro, Ky. They were then “owned” by David and John Hart, that is the girls were — but the boy was rather the “property” of Thomas Pointer. Any information will be gladly received by their sorrowing mother, Catherine Mason, at 1818 Hancock St., between Master and Thompson, Phila.

The duration of some separations was staggering. Some people lost relatives to sale as late as 1864, as slaveholders held on to the belief that slavery would survive the Civil War. Some lost husbands and fathers when they went off to fight in the war. Others had been gone for several years, and still others were missing for decades. It is likely that those who searched after a long time had created other significant relationships in their lives; they may have remarried or had other children, but the memories and the caring lingered.

Even now the immensity of their loss, the persistence of their longing, and the depth of their grief are evident in the ads. One can almost feel them expectantly reaching out for any shred of information to hold on to.

Christian Recorder, March 17, 1866

information wanted

I had two children sold from me about ten years ago by a man by the name of Pate, then living with James Evans. My boy’s name was Monroe Early, and my daughter’s name Mary Early. Any information of their whereabouts may be sent to the care of Rev. Wm. D. Hains, pastor of 3rd st A.M.E. Church, Richmond, Va.

Francis Early

Christian Recorder, June 24, 1865

Information wanted

Can anyone inform me of the whereabouts of John Person, the son of Hannah Person, of Alexandria, Va., who belonged to Alexander Sancter. I have not seen him for ten years. I was sold to Joseph Bruin, who took me to New Orleans. My name was then Hannah Person, it is now Hannah Cole. This is the only child I have and I desire to find him much. Any information of his whereabouts can be directed to Hannah Cole, Cedar St., New Bedford, Massachusetts

The ads are laden with pathos and expectancy, and they speak of hope and memory. But even people with the strongest sense of hope and who deployed all their scraps of information and resources must have sometimes despaired that the geographical and temporal distances, the instability of names, and the paucity of registries made success impossible. They must have wondered at times if it was worth their investment of money and emotion.

But, it seems, the intensity of their loss and the strength of their desires propelled them to make one more effort. And every once in a while it worked. The Southwestern Christian Advocate published this update in March 1877.

A Family Re-united

In the southwestern of March 1st, we published in this column a letter from Charity Thompson, of Hawkins, Texas, making inquiry about her family. She last heard of them in Alabama years ago. The letter, as printed in the paper was read in the First church Houston, and as the reading proceeded a well-known member of the Church — Mrs. Dibble — burst into tears and cried out “That is my sister and I have not seen her for thirty three years.” The mother is still living and in a few days the happy family will be once more re-united.

From Help Me to Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery by Heather Andrea Williams. Copyright © 2012 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.unc.edu

1South Carolina Leader (Charleston), May 12, 1866; Leon Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (New York: Knopf, 1979), 411–12; Ira Berlin, Slaves without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South (New York: Pantheon, 1974), 216–28; Tommy L. Bogger, Free Blacks in Norfolk, Virginia, 1790–1860: The Darker Side of Freedom (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997), 53; James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, In Hope of Liberty: Culture, Community, and Protest among Northern Free Blacks, 1700–1860 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 114; Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 96, 265.

2Advertisers in the church-sponsored Christian Recorder were particularly aware that the paper had the potential to reach large numbers of people. The African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded in resistance to the insults of a white Methodist Episcopal congregation in Philadelphia in 1816, had been allowed to exist in Baltimore and New Orleans until exposure of the Denmark Vesey conspiracy in 1822, in Charleston. With emancipation came expansion into southern states, along with broader distribution of the newspaper. Black Baptist congregations had also existed in some areas of the South during slavery; some operated fairly independently, while others were under the watchful eyes of white ministers. These churches also multiplied following emancipation. See Reginald Hildebrand, The Times Were Strange and Stirring: Methodist Preachers and the Crisis of Emancipation (Durham: Duke University Press, 1995), xxiii, and Albert Raboteau, Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 204–7, 196–204.

3Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom (New York: Dover Publications, 1855, 1969). Regarding name change due to escape, (1855), 342.