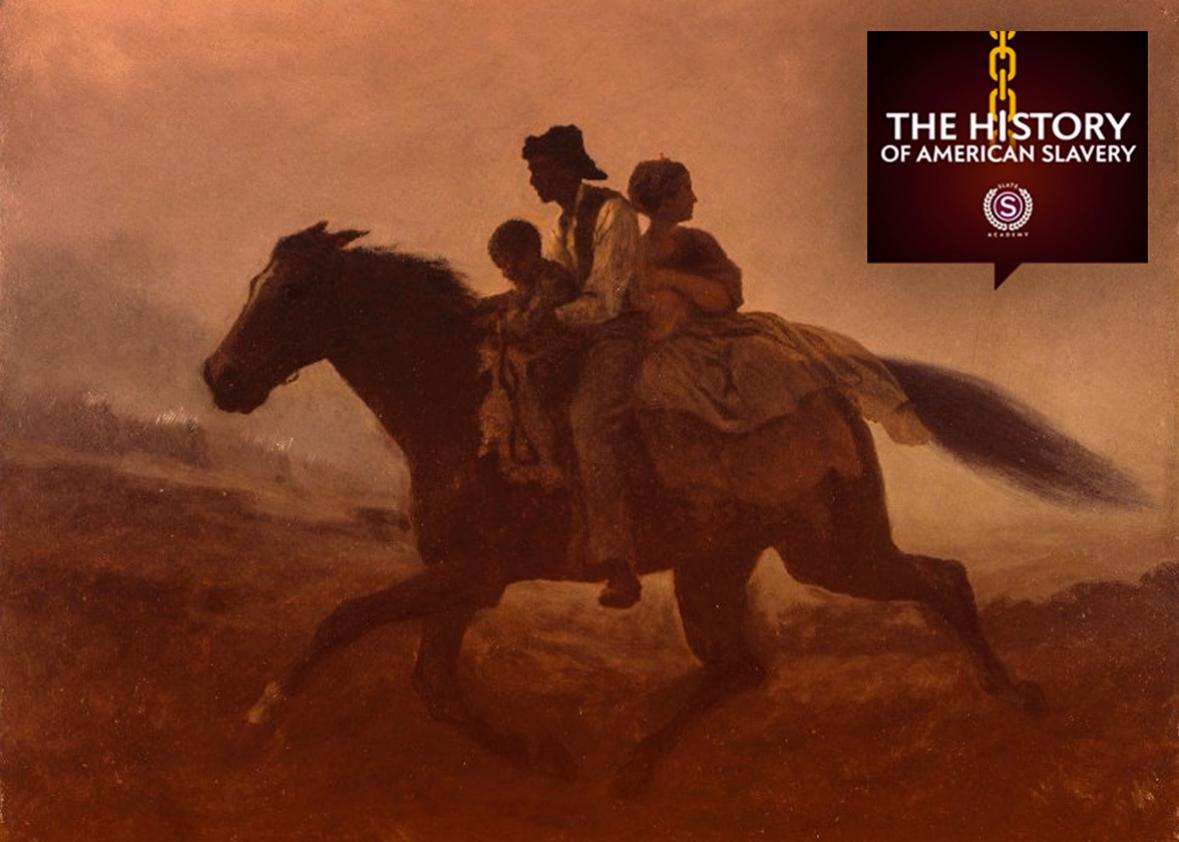

This article supplements Episode 8 of The History of American Slavery, our inaugural Slate Academy. Please join Slate’s Jamelle Bouie and Rebecca Onion for a different kind of summer school. To learn more and to enroll, visit Slate.com/Academy.

Excerpted from Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad by Eric Foner. Published by W. W. Norton & Company.

In popular memory, the individual most closely associated with the Underground Railroad is Harriet Tubman. Born a slave in Maryland in 1822, this remarkable woman escaped in 1849 and during the following decade made at least 13 forays to her native state, leading some 70 men, women, and children, including a number of her relatives, out of bondage.

Twice in 1856, Tubman brought fugitive slaves through Sydney Howard Gay’s office in New York City. In May, Gay recorded, “Captain Harriet Tubman” arrived with four fugitive slaves—Ben Jackson, James Coleman, William Connoway, and Henry Hopkins—from Dorchester County on Maryland’s eastern shore, the center of slavery in the state.

The exploits of Harriet Tubman are related in the Record of Fugitives, a document compiled by Gay in 1855 and 1856, as well as in scattered notes on runaway slaves that he also penned. In these two years, Gay meticulously recorded the arrival of more than 200 fugitives in New York City: 137 men, 44 women, 4 adults whose sex he failed to mention, and 29 children. Gay set down information about their owners, motives for leaving, mode of escape, who assisted them, where he sent them, and how much money he expended.

Gay’s account of Tubman’s passage through the city in May 1856 is the longest entry in his journal, a reflection of the high regard in which he held her. Gay also seems to have been the only person at that time who referred to her as “Captain” Tubman, which suggests that he knew her, or of her activities, before 1856.1 In many ways, Tubman’s activities were unique. But in others, the escapes she engineered were typical of many in these years.

Gay’s Record is the most detailed account in existence of how the Underground Railroad operated in New York City, and of the fugitives who passed through the city. He chronicled the experiences of slaves who escaped individually and in groups, by rail, by sea, on foot, and in carriages appropriated from the owners. Like Tubman’s charges, nearly half the slaves who appear in Gay’s Record originated in Maryland and Delaware, the eastern slave states closest to free soil. Some reached the free states within a day or two of their departure; others hid out for weeks or months in swamps or woods before moving on.

When supplemented with information compiled about many of the same individuals by William Still in Philadelphia, Gay’s Record is a treasure trove of riveting stories and a repository of insights into both slavery and the Underground Railroad.

To a Glasgow audience in 1853, the abolitionist James Miller McKim described the fugitives who arrived at the antislavery office in Philadelphia, many of them headed for New York: “These were not ill-treated slaves who had braved death and suffered so much to get their liberty. … It is those which have indulgent masters … that escape from slavery.” McKim’s point was that the desire for freedom, not the brutality of individual owners, led to escapes.

Some fugitives who passed through New York fit McKim’s description, such as James Jones of Alexandria, who, Gay recorded, “had not been treated badly, but was tired of being a slave.” Charles Carter, the slave of a flour inspector in Richmond, spoke of his owner “rather favorably in comparison with slaveholders generally … he has not been so badly abused as many others.”

But these were exceptions. Few fugitives interviewed by Still and Gay had anything good to say about their treatment. Even if the desire for freedom was the underlying motive, the decision to escape usually arose from an immediate grievance. And among the causes mentioned for running away, by far the most common was physical abuse.2

The fugitives who arrived in New York told stories replete with accounts of frequent whippings and other brutality; their words of complaint included “great violence,” “badly treated,” “ruff times,” “hard master,” “very severe,” “a very cruel man,” and “much fault to find with their treatment.”11 Frank Wanzer called his owner Luther Sullivan, who operated a plantation in Fauquier County, “the meanest man in Virginia.” John Haywood related how his brother had been shot dead after physically resisting a whipping.3

Second only to physical abuse as a motive for escape was the ever-present threat of sale. The marketing of slaves to the Lower South had long since become a lucrative enterprise for Upper South owners. Many of the slaves mentioned by Gay ran away to avoid being placed on the auction block or fled after members of their families had been sold. In an advertisement seeking his capture that ran six times in the Baltimore Sun, William Elliott claimed that his slave William Brown had run off “without the slightest provocation.” Brown, however, told Gay that he absconded because “he was to have been sold to go to Georgia.” Despite a history of harsh treatment, Franklin Wilson told Gay, he left Delaware only after he “overheard his master chattering with a stranger for his sale.” Phillis Gault, a widow who worked for a Norfolk woman as a dressmaker, “had witnessed the painful sight of seeing four of her sister’s children sold on the auction block, on the death of their mother,” and feared that she herself would soon be sold.4

The fugitives’ experiences also made clear the danger of relying on an owner’s promises, even if well-intentioned. Laura Lewis of Kentucky told Gay that her owner, who died 25 years previously, provided for the emancipation of his slaves on the death of his wife. The widow passed away in March 1855, but her creditors moved to have the will set aside and the slaves sold to satisfy her debts. Jacob Hall of Maryland had been verbally promised his freedom when he reached the age of 21, but when his owner died before that date the heirs reneged on the commitment and sold him.

In powerful, contradictory ways, family ties affected slaves’ decisions about running away. Escape from slavery generally involved wrenching choices about whether family members should leave or stay. A few fugitives, like Frederick Douglass before them, had free spouses or fiancés who could readily join them on free soil or had already traveled there. And when slaves escaped in groups, as in the case of Tubman’s rescues, these frequently included relatives—husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, even, as in the case of 11 women or married couples and one man in Gay’s records, small children.

Nonetheless, most of the fugitives listed by Gay left relatives behind in the South. William Henry Larrison abandoned his wife of one month; Major Latham, his wife and three children. Most of the women on Gay’s list were either unmarried or brought children with them, but occasionally, mothers left children behind when they escaped.5 Many runaways hoped that family separations would not prove permanent. Charles Carter told Gay that he was “determined to get” his wife and four children “somehow.”6

While the popular image of the Underground Railroad tends to focus on lone fugitives making their way north on foot, in fact more slaves who passed through New York in the mid-1850s escaped in groups than on their own.

Gay’s records offer a glimpse of the many methods slaves employed to flee their owners and the ingenuity their escapes involved. In addition to the groups that secured passage on boats like Capt. Albert Fountain’s ship, the City of Richmond, many fugitives arranged individually with captains for their passage (often for a sizable fee), were hidden on ships by sympathetic crew members, or stowed away without anyone’s knowledge.7

Some fugitives emulated Frederick Douglass and departed from Baltimore or other cities by train. Nathaniel West, who worked in Barnum’s City Hotel in Baltimore, “bought a ticket at the depot, and came off in the cars like a gentleman.”8

Another common mode of escape involved appropriating horses or carriages. Mary Cummens, her adult son James, 11-year-old daughter Lucy, and another slave, all owned by the wealthy planter Jacob Hollingsworth of Hagerstown, Maryland, rode off in his horse-drawn carriage to Shippensburg, where they boarded a train to Harrisburg and Philadelphia.9

Many slaves had no alternative but to try to escape on foot, sometimes over very long distances. Simon Hill, a slave in Appomattox County, Virginia, told Gay that he “took … to the woods, and bent his steps northward and in about two weeks reached Philadelphia,” a distance of more than 200 miles. Even those who initially escaped by other means ended up having to walk significant distances. The brothers Albert and Anthony Brown, owned by a Virginia oysterman, appropriated one of his boats and sailed up Chesapeake Bay until headwinds forced them to make landfall just north of Baltimore. From there, they walked by night, following railroad tracks. They traveled with the aid of a compass, but abandoned the instrument at some point “lest it should excite the suspicions of two white persons whom they saw approaching.” When they arrived in Wilmington, “friends” sent them on to Philadelphia and New York.10

Into 1860, Sydney Howard Gay continued to keep an account of expenses related to the Underground Railroad, but he no longer maintained his Record of Fugitives. Thus, it is difficult to know how many fugitives passed through New York in the years immediately preceding the Civil War. But there is no question that they continued to come.11

In the late 1850s, hundreds of fugitives entered Canada via upstate New York, and from Detroit, Cleveland, and other cities. Escapes, McKim reported from Philadelphia late in 1857, were “100 per cent more numerous than they were this time last year.” Fifty fugitives had “passed through the hands of the Vigilance Committee” in the past two weeks. Early in 1860, Stephen Myers declared that more fugitives had arrived in Albany in the past three years than in the previous six.

As the number of fugitives increased in these years, articles in the Southern press about the Underground Railroad became more and more frequent. Some slaveowners feared these reports actually encouraged escapes. The South’s slaves, the Richmond Whig insisted, “are the happiest and best cared for laboring population in the world.” But, it warned, the “weak mind of the slave” might be adversely affected by accounts of the “operations of the underground railroad.” “Is there no way to break up this ‘railroad’?” wondered another Virginia newspaper. The fugitive slave issue continued to roil national politics as the irrepressible conflict careered toward its final crisis.12

The Underground Railroad, James Miller McKim quipped, was the “only branch of industry” that “didn’t suffer” during the Panic of 1857: “Other railroads are in a declining condition and have stopped their semiannual dividends, but the Underground has never done such a flourishing business.”13

Excerpted from Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad by Eric Foner, Copyright © 2015 by Eric Foner. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

1. John Brown, who met Harriet Tubman in Canada in 1858, referred to her as “General Tubman.” Sernett, Harriet Tubman, 77.

2. NAS, October 8, 1853; Record of Fugitives, October 13, 26, 1855, April 4, 30, July 9, December 30, 1856; Still, Underground Railroad, 335–36, 380–81; Journal C, April 10, 1856.

3. Record of Fugitives, October 26, 1855, April 18, July 11, 1856; Statement of James Morris, undated, GP; Still, Underground Railroad, 119–20, 314–15.

4. Record of Fugitives, October 26, December 21, 1855, July 23, 1856; Journal C, November 29, 1855.

5. Record of Fugitives, January 17, July 22, 23, 28, September 17, November 10, 1856; Journal C, December 20, 1855, January 3, 1856.

6. Record of Fugitives, November 17, 1855, April 11, September 17, 1856.

7. Record of Fugitives, March 17, 20, 27, April 2, 1856; Note on Albert McCealee and John Edward Dayton, December 30, 1856, GP.

8. Record of Fugitives, September 1, 1855, March 27, May 15, 26, 1856; Still, Under- ground Railroad, 214, 222; BS, May 22, 24, 28, 29, 1856.

9. Record of Fugitives, April 3, May 28, December 5, 1855, January 4, June 5, 1856; PF in Anti-Slavery Reporter (London), May 1, 1856, 103–4; Still, Underground Railroad, 114–15, 219; Journal C, January 2, 1856; Canada Census, 1861.

10. Record of Fugitives, August 30, September 5, 7, December 21, 1855, September 17, 1856.

11. NAS, March 6, 1858; NYH, January 5, 1860; New Account with William H. Leon- ard, 1859, Record of Fugitives. The Anti-Slavery Standard Account Book in the Gay Papers at the New York Public Library records numerous small payments to Louis Napoleon between 1857 and 1861.

12. Richmond Whig, May 26, 1857; Alexandria Gazette, December 18, 1857.

13. James Miller McKim to Maria Weston Chapman, November 19, 1857, AC; Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement (New York, 2005), 408–11; Liberator, May 28, 1858; Stephen Myers to John Jay II, January 2, 1860, JJH.