Excerpted from Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves by Adam Hochschild. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Co.

This article supplements Episode 2 of the History of American Slavery, our inaugural Slate Academy. Please join Slate’s Jamelle Bouie and Rebecca Onion for a different kind of summer school. To learn more and to enroll, visit Slate.com/academy.

In the spring of 1789, in the same month that the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade sent the pioneering British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson to campaign against the slave trade in France, a freed British slave, Olaudah Equiano, set off on a mission of his own. Calling on a clergyman named Jones at Trinity College, Cambridge, he handed him a letter:

Dear Sir,

I take the Liberty of introducing to your Notice Gustavus Vasa, the Bearer, a very honest, ingenious, and industrious African, who wishes to visit Cambridge. He takes with him a few Histories containing his own life written by himself, of which he means to dispose to defray his Journey. Would you be so good as to recommend the Sale of a few and you will confer a favour on your already obliged and

obedient Servant,

Thomas Clarkson.

Still known by his slave name, Olaudah Equiano had written his autobiography, now considered the first widely read and influential slave narrative. The visit to Trinity College was the beginning of what would be an epic-length book tour.

Equiano was no stranger to the printed word. In the preceding two years he had written some dozen forceful letters to London newspapers, praising new anti-slavery books, defending abolitionist friends, and protesting a pro-slavery speech he had heard from the House of Lords visitors’ gallery. Knowing that George III was hostile to abolition, he wrote instead to the queen. He also signed—and probably organized and drafted—more than a half-dozen joint letters about slavery from groups of black men in London, who once or twice referred to themselves as the “Sons of Africa.” He did not shy from controversy, and even strongly praised intermarriage—something never endorsed by white abolitionists. For well over a century to come, it would be almost unheard of for anyone to speak as Equiano did in one open letter to a West Indian plantation owner:

A more foolish prejudice than this [against interracial marriage] never warped a cultivated mind. … Why not establish intermarriages at home, and in our Colonies? and encourage open, free, and generous love upon Nature’s own wide and extensive plan … without distinction of the colour of a skin?

In this stream of letters to the press, he at least once subtly touted the autobiography he was preparing, and when it appeared, its two volumes totaled 530 pages: The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa the African. At seven shillings—about $48 today—it became a best-seller. The Interesting Narrative was quickly translated into German, Dutch, and Russian, and during the three years after publication was the sole new literary work from England reprinted in the United States.

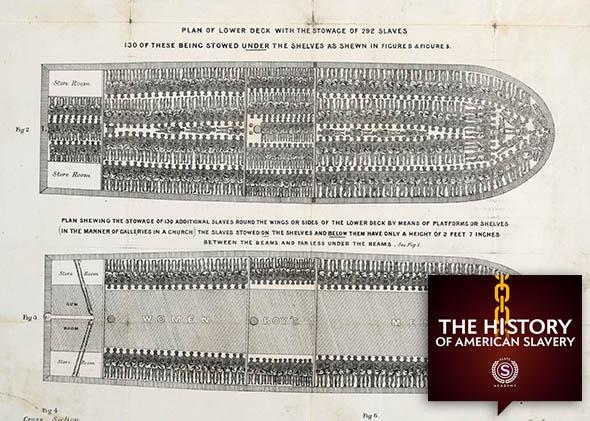

Its timing could not have been better. As the book appeared in the spring of 1789, the privy council was winding up its hearings, the abolition committee was plastering the country with slave ship diagrams, and William Wilberforce was arguing for abolition in the House of Commons. Equiano, who clearly saw his writing as part of the campaign, began the book with a petition addressed to Parliament and ended it with his anti-slavery letter to the queen. His was the first great political book tour, and never was one undertaken with more determination. He began in London, then went on to other cities, later writing to a sympathetic clergyman in Nottingham: “I trust that my going about has been of much use to the Cause of the abolition of the accu[r]sed Slave Trade—a Gentleman of the Committee the Revd. Dr. Baker has said that I am more use to the Cause than half the People in the Country—I wish to God, I could be so.”

Nothing is of more use to a cause than a person who seems to embody it, as, in our own time, the cause of freedom in Tibet has seemed embodied by the Dalai Lama or in apartheid-era South Africa by Nelson Mandela. The tens of thousands of Britons who read Equiano’s book or heard him speak got to see slavery through the eyes of a former slave.

And wherever he went, Equiano demonstrated his skills of promotion and diplomacy. He offered a discount to readers who bought six copies or more of his book; there was also a deluxe edition “on Fine Paper, at a moderate advance of price.” After a particularly friendly welcome in Birmingham, one of the new manufacturing cities now becoming anti-slavery strongholds, he wrote the local newspaper, thanking by name more than 30 people whose “Acts of Kindness and Hospitality have filled me with a longing desire to see these worthy Friends on my own Estate in Africa, when the richest Produce of it should be devoted to their Entertainment; they should there partake of the luxuriant Pine-apples and the well-flavoured virgin Palm Wine, and to heighten the Bliss, I would burn a certain kind of Tree, that would afford us a Light, as clear and brilliant as the Virtues of my Guests.”

In the midst of his book tour, a newspaper reported that Equiano, “well known in England as the champion and advocate for procuring a suppression of the Slave Trade, was married at Soham, in Cambridgeshire to Miss Cullen daughter of Mr. Cullen of Ely, in the same County, in the presence of a vast number of people assembled on the occasion.” Equiano did not know his year of birth but was probably in his mid-40s. Except that he was putting his belief in intermarriage into practice, we know next to nothing about his new wife, whom he may have met through his friendship with the Rev. Peter Peckard, the abolitionist vice chancellor of Cambridge. But his focus on selling his book pushed even his marriage into the background, for he wrote his Nottingham friend shortly before the wedding, “I now mean … to … take me a Wife … & when I have given her about 8 or 10 Days Comfort, I mean Directly to go [to] Scotland—and sell my 5th. Editions.”

Any publisher would be delighted to have such an energetic salesman as an author. Equiano, however, was his own publisher, something more common then than it is today. Self-publishing promised him more profit. Unlike many white abolitionists, he had no family wealth or connections to fall back on, and in his early years he had had the bitter experience of white people cheating him out of money due him.

Publishing his own book was a successful business move, just like the trading deals he had made while still a slave earning money to buy his freedom. The book caught on quickly and the first edition of more than 700 copies was soon sold out. He issued eight more editions of the Interesting Narrative during his lifetime, each prefaced by an ever-lengthening list of “subscribers”—people who had ordered copies and paid half the book’s price in advance, thereby financing the printing costs.

The subscriber list at the front of Equiano’s first edition included the bishop of London, plus an impressive roster of MPs, earls, dukes, and even the pro-slavery Prince of Wales—how Equiano got to him we do not know. He would round up similar lists of notables from the provincial cities where several later editions appeared: 211 people in Hull, 248 in Norwich, and the majority of the professors at the University of Edinburgh. Eventually his subscriber list totaled well over 1,000, some of them buying multiple copies. The pioneer feminist Mary Wollstonecraft reviewed it, and Methodism’s founder, John Wesley, read it on his deathbed.

Being his own publisher gave Equiano control over every aspect of his book. For the frontispiece to the first volume, for instance, he chose an engraving of himself. The image is one of only a handful from the England of this time that show black men or women whose identities we know. Gazing straight at the viewer, Equiano holds an open Bible and wears the gentlemanly attire of the day: ruffled cravat, waistcoat, elegant jacket, lace cuffs. The artist has made no attempt to Europeanize his features; his curly hair, dark skin, and thick lips mark him as a proud African. The frontispiece to the second volume shows a scene from his adventurous life, of Equiano rescuing some white fellow sailors after a shipwreck.

Equiano essentially spent the rest of his working life on a book tour. For more than five years he crisscrossed the British Isles. In Ireland, where activists were agitating for better representation in Parliament and against their status as second-class citizens, he met an especially receptive audience, selling 1,900 copies during an 8½-month stay. He found that the Irish, too, felt themselves to be victims of oppression. He was in Ireland when a procession wound through the streets of Belfast to celebrate the second anniversary of the fall of the Bastille. On one side of a great banner was a scene of a crowd storming the prison; on the other was a chained figure representing Ireland; the next banner in the parade denounced the slave trade. This was a heady mix, a sign of rising democratic hopes in a world where up until now hierarchy and domination had been the order of the day.

The Interesting Narrative said much that abolitionist literature by whites could not. Although Equiano’s pages on the middle passage and the horrors of West Indian slavery are searing, he knew that most of his audience had by now heard such stories. Nor does he devote much space to the familiar argument that Britain’s businessmen had much more to gain from legitimate trade with Africa (“except,” he wryly noted, “those persons concerned in the manufacturing [of ] neck-yokes, collars, chains, hand-cuffs, leg-bolts … thumb-screws, iron-muzzles …”).

Instead, most of the book is the tale of his own redemptive passage from freedom in Africa through slavery to precarious freedom in England. Equiano wrote with a modern, personal sensibility; he had obviously noticed the huge impact on readers of John Newton’s and Alexander Falconbridge’s eyewitness accounts and the similar effect on audiences when he spoke of his experiences. He knew that the most powerful argument against slavery was his own life story.

When Equiano brought his book into the world in 1789, most Britons thought of Africans as heathen illiterates, with minds and bodies alike scorched into strangeness by the intense heat of the tropics. Now suddenly here was a man who was Christian, who could wield the English language well, who had earned his freedom by his skill in trading, who had learned to navigate and to play the French horn. Could any reader imagine a more impressive tale of rising in the world through the hard work that the British prized so dearly? “I … embraced every occasion of improvement,” wrote Equiano of his early days in England, “and every new thing that I observed I treasured up in my memory.” He presented himself, in short, as an estimable black Englishman.

Equiano had noticed the most popular forms of literature around him—the adventure travelogue, the riches-to-rags-to-riches tale, the religious convert’s testimony —and skillfully combined elements of them all. But, more important and lasting, the Interesting Narrative is the voice of a brave, resourceful, and compassionate man who on occasion risked much to help those still trapped in slavery. Equiano put on paper a story matched by none of his contemporaries, and one that has lasted. Of the hundreds of books that argued for freedom for the British Empire’s slaves, his is the only one a reader can easily find in a British or American bookstore today. Each year more people read it than did so during his entire lifetime.

Excerpt from Bury the Chains by Adam Hochschild. Copyright (c) 1998 by Adam Hochschild. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Co. All rights reserved.