Shibboleth. Casuistry. Recondite.

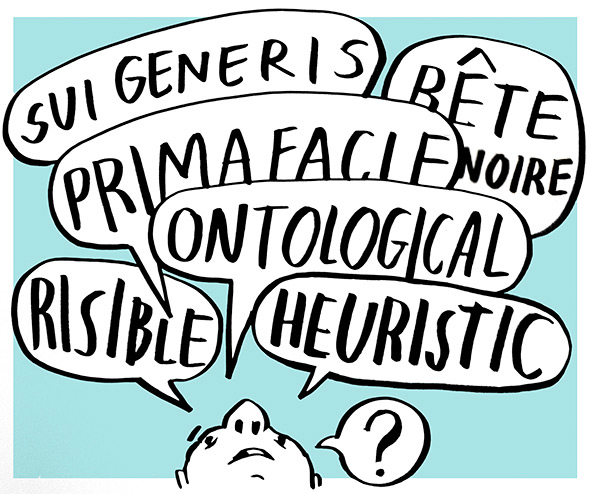

Bubble vocabulary: the words you almost know, sometimes use, but are secretly unsure of.

Illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

A little while back, I was chatting with a friend when he described a situation as “execrable.” He pronounced it “ex-EH-crable.” I’d always thought it was “EX-ecrable.” But execrable is a word I’d mostly just read in books, had rarely heard spoken, and had never once, in my whole life, uttered aloud—in large part because I wasn’t exactly sure how to say it, and because the nuances of its definition (beyond “bad”) escaped me.

Since we have a trusting, forthright relationship, I decided to broach the topic. “Is that how you pronounce that word?” I asked. “And what exactly does it mean?” Here my friend confessed he was not 100 percent certain on either count. He added that, earlier that same day, he’d pronounced avowed with three syllables and then immediately wondered if it might only have two.

We’ve all experienced moments in which we brush up against the ceilings of our personal lexicons. I call it “bubble vocabulary.” Words on the edge of your ken, whose definitions or pronunciations turn out to be just out of grasp as you reach for them. The words you basically know but, hmmm, on second thought, maybe haven’t yet mastered?

See if you can beat Slatesters at their bubble words.

Complete!

« Start Over

A certain Slate podcaster says he once stopped himself from asking a question on air because he wasn’t sure how to pronounce correlative. Another podcaster used mordant to mean morbid—at which point she became uncertain and did a retake to fix the error. A third mentioned that he’s “afraid to throw out a folderol” on air for reasons of both meaning and pronunciation.

Personally, it’s when I encounter Latin terms that I come up against my linguistic Waterloo. Prima facie. De minimis. Sui generis. I’m hugely impressed when others squeeze these into spoken discourse. I’m terrified to use them myself and, ipso facto, never do.

I could sense the hot-cheeked embarrassment among my fellow Slate-sters when I asked them to recall past bubble vocab fails. One editor recounted that she pronounced palliative as “puh-LIE-a-tive” during a Slate meeting, and then felt dumb when ensuing speakers pronounced it the right way. Another staffer remembered the time he pronounced epitome as “EPP-i-tohm” in high school, and then, to his eternal mortification, insisted he was right after his teacher gently corrected him. And let us all extend our sympathies to the video producer who repeatedly spoke of “de-NOO-mint” in a college film class. Even lexicographical luminaries like David Foster Wallace have experienced bubble vocab moments. “In my very first seminar in college,” Wallace revealed in a live online chat in 1996, “I pronounced facade ‘fakade.’ The memory's still fresh and raw.”

(And just in case that last paragraph popped your bubble: It’s “PAL-ee-a-tiv,” “epp-IT-uh-me,” “DAY-noo-mahn,” and “fuh-SOD.”)

But is reaching for bubble vocabulary actually shameful? To our discredit, we do seem especially tempted to stretch our linguistic wings in the middle of a job interview, an all-staff meeting, a college seminar, or a radio segment. These are, not coincidentally, occasions when we might wish to appear a smidge more erudite than we really are. (Bubble vocab alert! Is that “air-yuh-dite” or “er-oo-dite”?)

But if our impulse to employ words that we don’t quite know is a bit peacocky, I don’t think we should feel chagrined when we’re cut down to size. Excessive abashment when our vocab goes wrong is, in my view, counterproductive. It has a chilling effect. We become reluctant to reach for the verbal brass ring the next time an opportunity comes along.

And that is a loss to us all. Juicy vocabulary words are a hoot. They are one of the great pleasures of conversation. They are to be applauded and savored. We shouldn’t hesitate to draw them from our quivers, even if we may occasionally miss our targets.

Granted, your star-making, debut close-up on the nightly news is perhaps not the ideal moment to pull a shaky vocab word out of your back pocket. But otherwise, let your freak gonfalon fly. Surely, we should not let ourselves be cowed in a work meeting, a classroom setting, or a casual tête-à-tête with a pal. (By the way, French phrases—such as objet d’art and cause célèbre—were mentioned by several Slate-sters as bubble vocab bêtes noires.)

Behind the scenes: Read the emails Seth's Slate coworkers sent him about their bubble words.

To create an environment that encourages bubble vocab leaps of faith, we must consider our response in the event that someone doesn’t stick the landing. What should we do if we hear someone else incorrectly attempt a sesquipedalian mot juste?

One school holds that you must let the error pass unmentioned, but this is, as one Slate-ster put it, like letting a friend leave lunch with pesto flecks in her teeth. Another tactic: the face-saving technique in which you, as soon as is possible after the mistake has occurred, pronounce the word the correct way within earshot of the offender—without acknowledging the earlier boner. A third camp advocates a more passive-aggressive tack: “Oh, is that how you pronounce that word?” they might inquire, with faux innocence. “I always thought misogyny had a soft g.” (And yes, I looked it up because I wanted to make sure: It’s a tack, not a tact.)

I side with the Slate copy editor who offers this wisdom, gleaned from an occasion on which he mispronounced risible as “rise-able”: “I was corrected in the very best way possible: quickly and reflexively by the corrector, without judgment, like an executioner with a sharp, dispassionate blade.” I further concur with his addendum: “The worst is when no one corrects you! Because then they are silently judging you instead of treating you as they would a friend.”

Let’s all treat each other as friends. Friends who make an effort to employ delectable words in conversation, but might occasionally mispronounce or misuse them. Friends who are unafraid to stir some spice into the verbal soup. Friends who also won’t hesitate to point out each other’s solecisms (which are not at all the same thing as solipsism, even if one of my friends admits she can never remember the difference).

So please share your own bubble vocab nightmares in the comments. And take comfort in this: Vocabulary is one of the few skills that improve as we get older. Some studies show you can count on reliable growth in the size of your vocabulary well into your 70s. So you don’t have arrogate and abrogate down cold, just yet. Give it time.

Email This

Email This