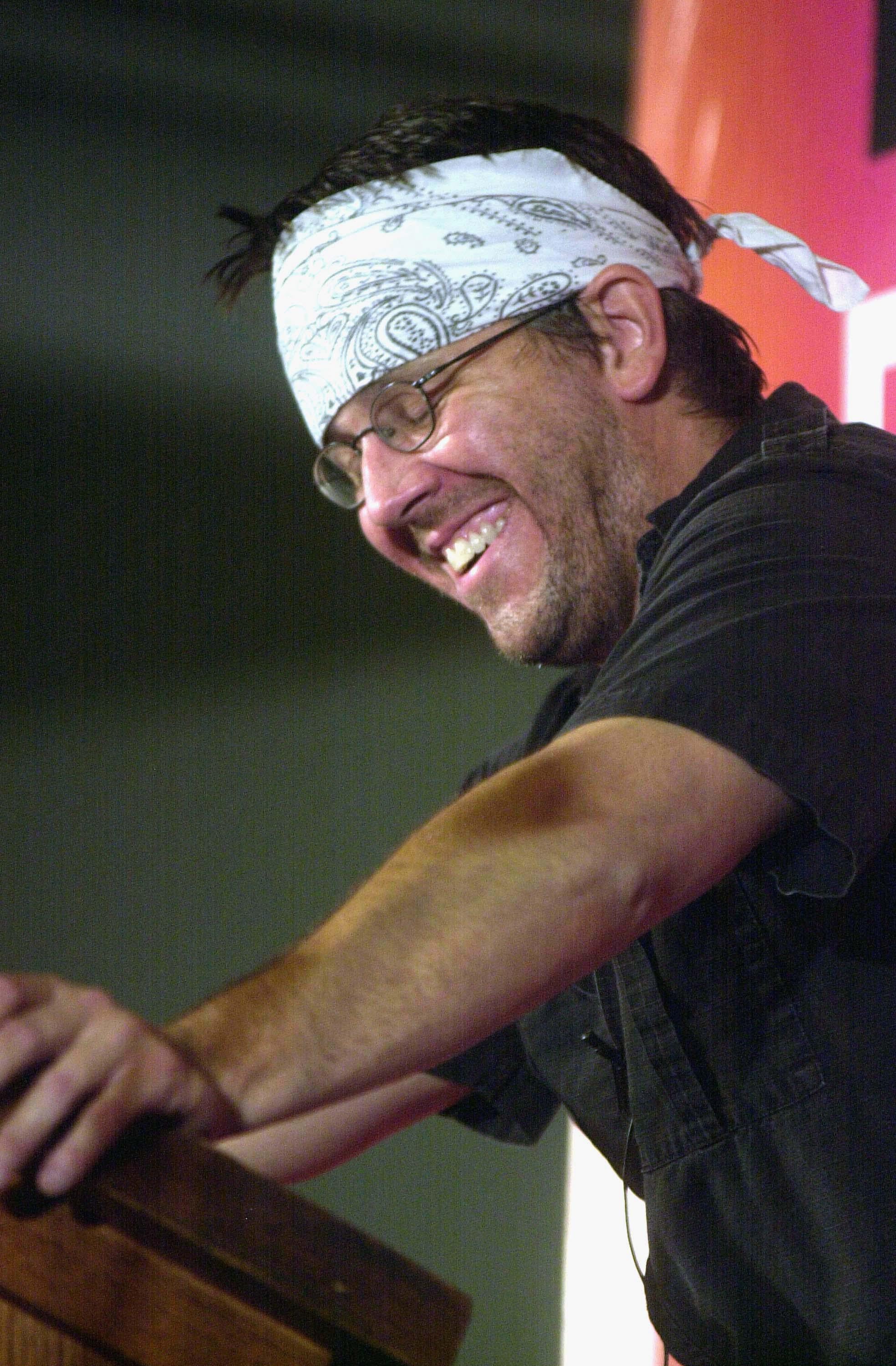

Lately David Foster Wallace seems to be in the air: Is his style still influencing bloggers? Is Jeffrey Eugenides’ bandana-wearing depressed character in The Marriage Plot based on him? My own reasons for thinking about him are less high-flown. Like lots of other professors, I am just now sitting down to write the syllabus for a class next semester, and the extraordinary syllabuses of David Foster Wallace are in my head.

I am not generally into the reverential hush that seems to surround any mention of David Foster Wallace’s name by most writers of my generation or remotely proximate to it; I am not enchanted by some fundamental childlike innocence people seem to find in him. I am suspicious generally of those sorts of hushes and enchantments, and yet I do feel in the presence of his careful crazy syllabuses something like reverence.

Wallace doesn’t accept the silent social contract between students and professors: He takes apart and analyzes and makes explicit, in a way that is almost painful, all of the tiny conventional unspoken agreements usually made between professors and their students. “Even in a seminar class,” his syllabus states, “it seems a little silly to require participation. Some students who are cripplingly shy, or who can’t always formulate their best thoughts and questions in the rapid back-and-forth of a group discussion, are nevertheless good and serious students. On the other hand, as Prof — points out supra, our class can’t really function if there isn’t student participation—it will become just me giving a half-assed ad-lib lecture for 90 minutes, which (trust me) will be horrible in all kinds of ways.”

One of the reasons I find his syllabuses so fascinating is that they are not polished pieces of writing. They are relatively devoid of his stylistic rococo, and while obviously not devoid of his astonishing level of self-consciousness, do provide some slight glimpse into the person, without the baffling ingenious mediation of his art.

Wallace refuses the habitual patterns and usual fictions that govern a classroom. His syllabus warns: “If you are used to whipping off papers the night before they’re due, running them quickly through the computer’s Spellchecker, handing them in full of high-school errors and sentences that make no sense and having the professor accept them ‘because the ideas are good’ or something, please be informed that I draw no distinction between the quality of one’s ideas and the quality of those ideas’ verbal expression, and I will not accept sloppy, rough-draftish, or semiliterate college writing. Again, I am absolutely not kidding.”

Students of course love teachers who step out of the formality of academic life, who comment on it, but very few do so as more than theater. Very few commit to it the way David Foster Wallace commits to it. “This does not mean we have to sit around smiling sweetly at one another for three hours a week. … In class you are invited (more like urged) to disagree with one another and with me—and I get to disagree with you—provided we are all respectful of each other and not snide, savage or abusive. … In other words, English 102 is not just a Find-Out-What-The-Teacher-Thinks-And-Regurgitate-It-Back-at-Him course. It’s not like math or physics—there are no right or wrong answers (though there are interesting versus dull, fertile versus barren, plausible versus whacko answers).”

Of course, this is not the part of teaching that most people pour their hearts into. It’s just a syllabus! Wallace is bringing to the endeavor rigorous Salingerish standards of not lying, or not being phony, that would reproach other more ordinary people if these standards did not border on parody, and were not expressed in such a good natured and honorable way.

Most of us operate on what Wallace elsewhere calls the “default setting;” we make a calculation about what is the right expenditure of energy for a syllabus; we make a sensible adult decision about preserving analytic brio for other things, and don’t think too much about it; we use the conventions, the years of worn-out tradition, as a shortcut to speed up communication. We assume we can just say “no late papers” or “class participation is 50% of the grade,” and everyone will know what we are talking about.

And for a sane person: why comment? Why try to take on and disentangle the unspoken tensions that may or may not take place in a classroom some months in the future? Why not, in other words, let sleeping dogs lie, exhausted students lean on their hands after a weekend of parties?

Is there something morally pure or preferable about David Foster Wallace’s painful intricate construction of a syllabus to the brisk, functional way most people toss off the task? I don’t know the answer to that. But there is a beauty in the documents, a seriousness that one can’t fail to be touched by. Even if parts or sections of Infinite Jest made you feel that it should in fact be a doorstop, much as you loved other parts of it, these syllabuses offer a quick encapsulation of many good and practically useful things about Wallace’s thinking, his shorthand lesson plan on how to live. In his commencement speech at Kenyon he told a parable about a fish not knowing what water is, and his point here and elsewhere is that you need to always think to yourself, “This is water.” As he puts it in that same speech, “It is about making it to thirty, or maybe even fifty, without wanting to shoot yourself in the head.”

There is in his syllabus no compromise with expediency, no taking for granted of power structures, nothing but rigorous honesty and tireless interrogation; there is some feeling or hope that if you could put every single thing under the sun into words you can head off sorrow, frustration, resentment, missed communication, thwarted ambition.

It is way easier of course to walk past, to not examine, to not take apart: There is a social use in seeing an ambulance rushing by without imagining who is inside it, in buying a quart of milk without thinking too deeply about the guy behind the counter at the bodega, in not being David Foster Wallace, in other words. The fish who is thinking obsessively “What is water?” is, we pretty much know, a little less likely to swim very far.

Still, every time I write or tinker with a syllabus, acceptable, professional, workable, with exactly the usual amount of spark, I think of David Foster Wallace. Maybe I’ll do it a little better this time.