This article supplements Reconstruction, a Slate Academy. To learn more and to enroll, visit Slate.com/Reconstruction.

Adapted from An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C. by Kate Masur. Published by the University of North Carolina Press.

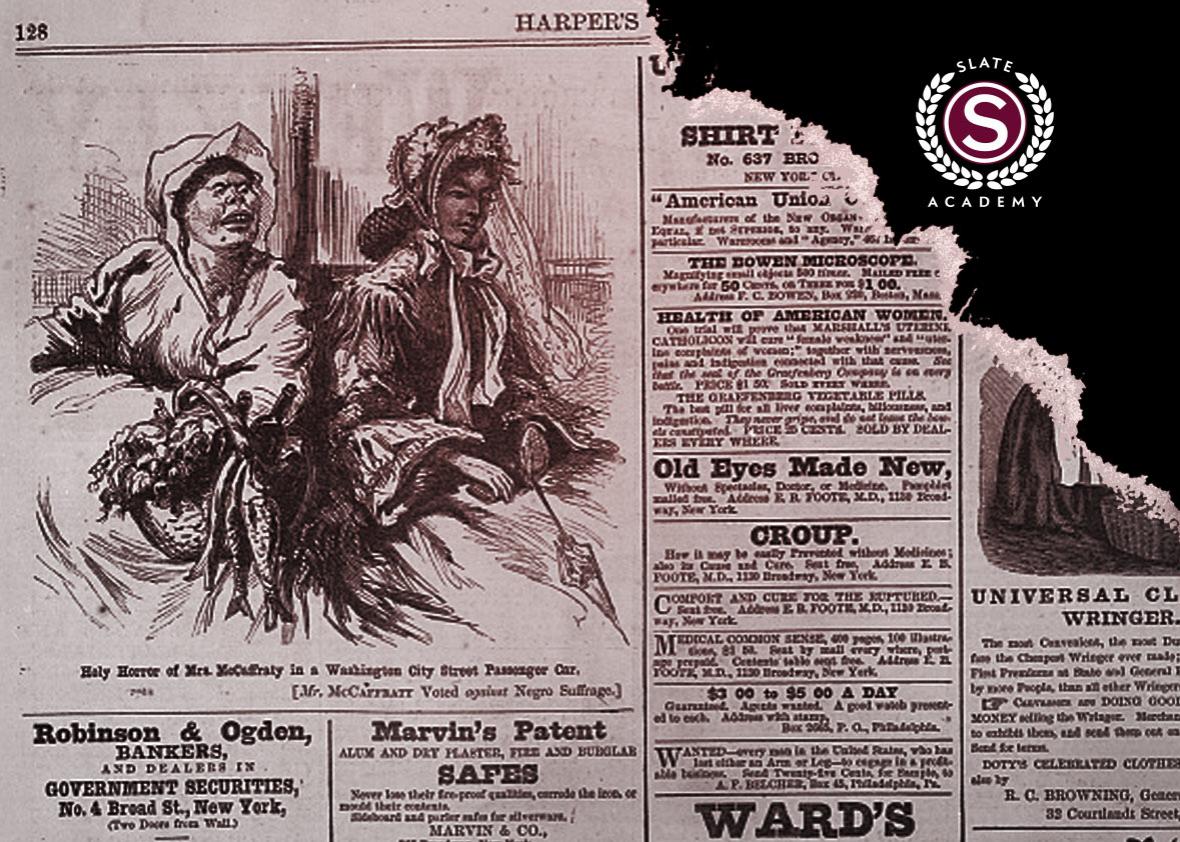

At 2 p.m. on a late February day in 1868, Kate Brown, an employee in the Senate, left work in the U.S. Capitol and boarded a train for Alexandria, Virginia. She planned to visit a relative and return to work about an hour later. Brown chose a seat in the car reserved for white “ladies” and their white male traveling companions. But Brown, who was by most contemporary descriptions “mulatto,” had no illusions about whom the “ladies’ car” was meant for. As she later put it, she had boarded “what they call the white people ’s car.”1 The alternative was the car designated for black Americans and white men not in the company of ladies. Often known as the smoking car, that car was a more promiscuous space in which people mingled in an environment with no pretensions of refinement or protectiveness. Brown did not care to mingle with the unruly public in the smoking car, and she believed she was entitled to ride in the ladies’ car if she had a ticket. A man standing on the Washington platform advised her to change cars, but Brown remained in her seat and had no further trouble.2

Brown also had every intention of returning to Washington in the ladies’ car. But when she boarded the train at the Alexandria depot a short time later, a special policeman (likely a security guard hired by the railroad) indicated that she must leave the ladies’ car. She refused. As she later testified: “I told him I came down in that car, and in that car I intended to return … he said I could not go; I asked him why … he said that car was for ladies; I told him then that was the very car I wanted to go in.”3 Not interested in debating, the policeman grabbed Brown and tried to pull her from the car. She held fast

to the inside of the door and braced her foot against the seat. When the policeman threatened to beat her, she told him he could go ahead: “I had made up my mind not to leave the car, unless they brought me off dead,” she averred.4

The policeman pounded Brown’s knuckles, twisted her arms, and grabbed her collar. He was soon joined by a man who called himself a “sheriff,” who held her by the neck and helped drag her out of the car and onto the platform. Brown estimated that the struggle on the Alexandria platform had lasted about 11 minutes, and she believed several white men had watched the entire incident. She later testified: “I declare they could not have treated a dog worse than they tried to treat me. It was nothing but ‘damned nigger,’ and cursing and swearing all the time.”5

The assault on Kate Brown at the Alexandria railroad depot became something of a local cause célèbre. The radical Republican Daily Chronicle called the incident a “disgrace to this age of civilization.” The newspaper contrasted Brown’s impeccable comportment with the barbarism of the “several representatives of the ‘chivalry’ of the South” who had attacked her. Radical Republicans in the Senate, who knew Brown as an employee, brought the incident to the attention of the entire Senate and argued that it demonstrated the inadequacy of existing civil rights laws. Brown also filed suit against the railroad company for damages, a move one unsympathetic federal official considered “a purposely got up case for the sake of a judicial row between the colors.”6

Kate Brown’s refusal to leave the ladies’ car and the steps she and others took in search of redress are particularly dramatic examples of a broader culture of protest that developed in the national capital during the 1860s.7 During the war and immediately afterward, black Washingtonians sought access to a remarkable range of arenas previously understood as the domain of white people only. These were not meek or quiet gestures. Rather, black Washingtonians demanded that white locals and federal officials consider their claims and respond to them.

In the volatile 1860s, no one knew what kinds of laws and customs would replace the vanquished world of slavery and the black codes. Even among northerners, there was widespread disagreement about the meaning of civil rights and the domain of equality before the law. Most Republicans agreed that there should be no racial restrictions on a set of basic “civil” rights, including an individual’s right to move from one place to another, nor should there be racial discrimination in legal proceedings. That consensus vision of racial equality was manifest in Congress’ 1862 eradication of the District ’s black codes. Yet those advances nonetheless left many urgent questions unanswered. As black Washingtonians quickly surmised, the abolition of the black codes had no bearing on a range of arenas in which racial equality was up for debate—including trains, streetcars, and other public accommodations. Nor did the formal codification of “equality before the law” guarantee that police would put that principle into practice.

Public accommodations were services run by private individuals or corporations for the public benefit. In common law, proprietors of public accommodations had a duty to serve the public and could not deny service arbitrarily. Their policies must conform to the principle of “reasonable regulation,” which allowed them to establish rules to preserve the peace, protect travelers, and cultivate the business itself. Thus, for example, proprietors could refuse to serve people who were drunk or ill, as their conditions might negatively affect other patrons or be disruptive to business. Whether proprietors could refuse accommodation to black Americans, or insist that they use segregated services, was very much in question. Some argued that such discrimination was arbitrary and therefore impermissible; others insisted that racial discrimination was a form of reasonable regulation that business owners could use to protect their business and the public peace.8

In Washington and other postwar cities, streetcars became a focal point in the debate over black Americans’ access to public accommodations. Unlike other public accommodations that were also under debate, including restaurants and fancy theaters, streetcars were not meant as accommodations for the elite. Because tickets were relatively inexpensive, streetcar travel was within reach for many working people. Moreover, because streetcars were single cars drawn by teams of horses, they offered fewer options for segregated seating than railroads. Streetcar companies did not sell first-class tickets or operate separate ladies’ accommodations, as the train that Kate Brown boarded did. The interiors of streetcars were typically mixed-class spaces, where laborers and middle-class people, men and women, congressmen and laborers shared a single car. In this, streetcars were distinctly urban institutions, characteristic of life in the country’s increasingly dense, populous, and diverse cities.9

Black Washingtonians began demanding equal access to streetcars during the Civil War. When black soldiers protested exclusion as they were being recruited during the summer of 1863, the capital’s one streetcar line inaugurated separate cars for black riders. The New York–based Anglo-African at first applauded the separate cars as a mark of progress, but the paper soon complained that the cars were inadequate to meet the growing demand by black riders.10

That winter, army surgeon Alexander Augusta made a high-profile protest after he was refused a seat on a streetcar while traveling on official business. Augusta outlined the incident in a letter to the military judge advocate and forwarded a copy to Sen. Charles Sumner, who read Augusta’s complaint in the Senate and insisted that more be done to safeguard the rights of black Americans to ride the city’s streetcars. The cars for black people only came “now and then, once in a long interval of time,” he argued, creating particularly severe hardships for women. It was a “disgrace to this city” and a “disgrace to this Government.”11 Sumner introduced into the new charter for the Metropolitan Railroad, the city’s chief streetcar company, a clause prohibiting “exclusion of colored persons from the equal enjoyment of all railroad privileges in the District of Columbia.”12

In the Senate, opponents of integration made perhaps their strongest case by citing railroad companies’ widespread practice of running separate cars for separate classes of travel. Railroads often ran ladies’ cars to which men could be denied access as well as smoking cars and refreshment cars, all of which were understood to be permitted under the common law principle of reasonable regulation. As Wisconsin Sen. James R. Doolittle explained, “public carriers” must “furnish a seat to every man who purchases a ticket and asks for a seat … and that is all they are bound to do.” If company managers decided the public was best served, and the peace best administered, by providing separate cars for black people and white people, such was their prerogative.

Others, however, argued that race and color were not varieties of difference that could be used in making distinctions among paying customers. Maryland Sen. Reverdy Johnson, a widely respected legal thinker, argued that there was no doubt that companies were allowed to preserve order within the cars but that prerogative did not mean they could make distinctions among law-abiding men.13 Charles Sumner and his allies in the Senate further insisted that recourse to the common law was not sufficient to the challenges black Americans faced. Whereas opponents argued that most black Americans were content with the situation as it stood (and that Alexander Augusta was merely a rabble-rouser), Sumner said people brought examples of injustice on the streetcars to his attention “almost daily.”

The debate brought disagreements over slavery and the future of black Americans to the surface, giving it a highly emotional and sectional tinge that may ultimately have pushed a few Republican moderates into Sumner’s camp. Delaware Sen. Willard Saulsbury argued that attempts to “equalize with ourselves an inferior race” were “insane.” White people who refused to ride streetcars with black Americans showed “good sense and good taste,” he claimed, before lambasting the North as the source of every awful “ ‘ism’ of the modern day”: “Woman’s rightsism, spiritualism, and every other ism, together with abolitionism.”14 Such arguments grated on Republican moderate Lot Morrill of Maine, who joined Sumner in arguing for the anti-discrimination language, not because he considered it legally necessary but because he interpreted border state senators like Saulsbury as defending the system of racial domination that had underpinned slavery. Saulsbury and his ilk had no problem riding with “colored men and women,” provided they wore upon themselves “the badge of bondage and servitude.” “It is in good taste to do that!” Morrill exclaimed sarcastically.15

Republicans did not agree on the lengths to which the federal government could go to ameliorate problems resulting from slavery, but they did agree on the imperative of ending slavery itself. Morrill had emphasized the measure’s close association with the abolition of slavery, and this may have helped secure the Senate votes necessary to pass the Metropolitan Railroad incorporation act with Sumner’s clause included.

Congress’ codification of black Americans’ right to ride the District’s streetcars was a significant innovation, not just because it represented a willingness to undertake progressive policy experiments in the capital but also because the concept of an individual right to ride was, itself, very new. Black Washingtonians had insisted that, once free, they must be entitled to full membership in the traveling public and to the privilege of using ladies’ or first-class accommodations if they so desired and could afford it. Their claims had pushed Congress to discuss the meaning of common law principles and the necessity for declaratory legislation where the common law was violated, and Congress had created a “right” to ride as a result. Questions about the boundary between public and private, and about the legitimacy of various kinds of discrimination, would remain crucial as Americans continued to debate the question of where—literally in what spaces—people’s civil rights began and ended.

Adapted from An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C. by Kate Masur. Copyright © 2010 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. www.uncpress.unc.edu.

1. Committee on the District of Columbia, Report. 40th Cong., 2nd sess., 1868, S. Rept. Com. 131, 12.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid., 13.

6. Benjamin Brown French, Witness to the Young Republic: A Yankee’s Journal, 1828-1870, ed. Donald B. Cole and John J. McDonough (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1989), 613.

7. For the larger story of Kate Brown and her protest, see Kate Masur, “Patronage and Protest in Kate Brown’s Washington,” Journal of American History, 99 (March 2013), 1047–71.

8. The principle of “reasonable regulation” is clearly explained in Barbara Y. Welke, “When All the Women Were White, and All the Blacks Were Men: Gender, Class, Race, and the Road to Plessy, 1855-1914,” Law and History Review, 13 (Autumn 1995), 273–74. For black Americans’ antebellum demands for access to railroads and streetcars, see also Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 270–71; and Louis Ruchames, “Jim Crow Railroads in Massachusetts,” American Quarterly, 8 (spring 1956), 61–75.

9. In Washington in the spring of 1865, a ticket cost seven cents when purchased from the conductor and less than six cents if bought in advance as part of a book. At the federal government ’s daily laborers’ wage of $2, the 12 cents required for a round-trip commute was about 6 percent of a day’s wages. Washington Chronicle, March 29, 1865.

10. Anglo-African, Nov. 7, 1863, Nov. 28, 1863. See also Sojourner Truth, Narrative of Sojourner Truth; a Bondswoman of Olden Time, With a History of Her Labors and Correspondence Drawn From Her ‘Book of Life,’ edited by Olive Gilbert (Battle Creek, Mich., 1878), 184.

11. Congressional Globe, 38th Cong., 1st sess., 1864, 553–54.

12. Ibid., 553 (emphasis added).

13. Ibid., CG, 38th Cong., 1st sess., 1864, 1156.

14. Ibid., 1141, 1158.

15. Ibid., 1159.