Each year in the U.S., about 5,000 pedestrians are struck and killed by drivers. That’s 12 a day, and the numbers are growing. In St. Louis, where I live, pedestrian-killing is apparently more popular than football. More times than I can count, as a law-abiding human in a marked crossing, with a clear signal or right of way, I’ve been screamed and honked at; I’ve been buzzed as drivers nosed over the stop line or ran red lights outright; I’ve been squeezed by right-turners and careened at by lefts.

Things are different when I visit my parents in bucolic Eugene, Oregon, land of the Country Fair and possibly-excessive chill, including among most motorists. But a recent near-miss has made me realize that even the kindest, mellowest drivers can be a threat to the unwitting pedestrian. Here’s a tip, frequent urban or suburban walker, about a deathtrap you might not be expecting.

As I approach the busy, multilane one-way street near my parents’ house, pushing my daughter’s stroller, a friendly driver in the nearest lane sees me approach, pulls to a stop, and waves me across. I step out into the crosswalk and begin the march across the street—only to be buzzed by a car in the next lane over, whose driver has no idea why the driver in the right lane has stopped. After all, she can’t see me any more than I can see her.

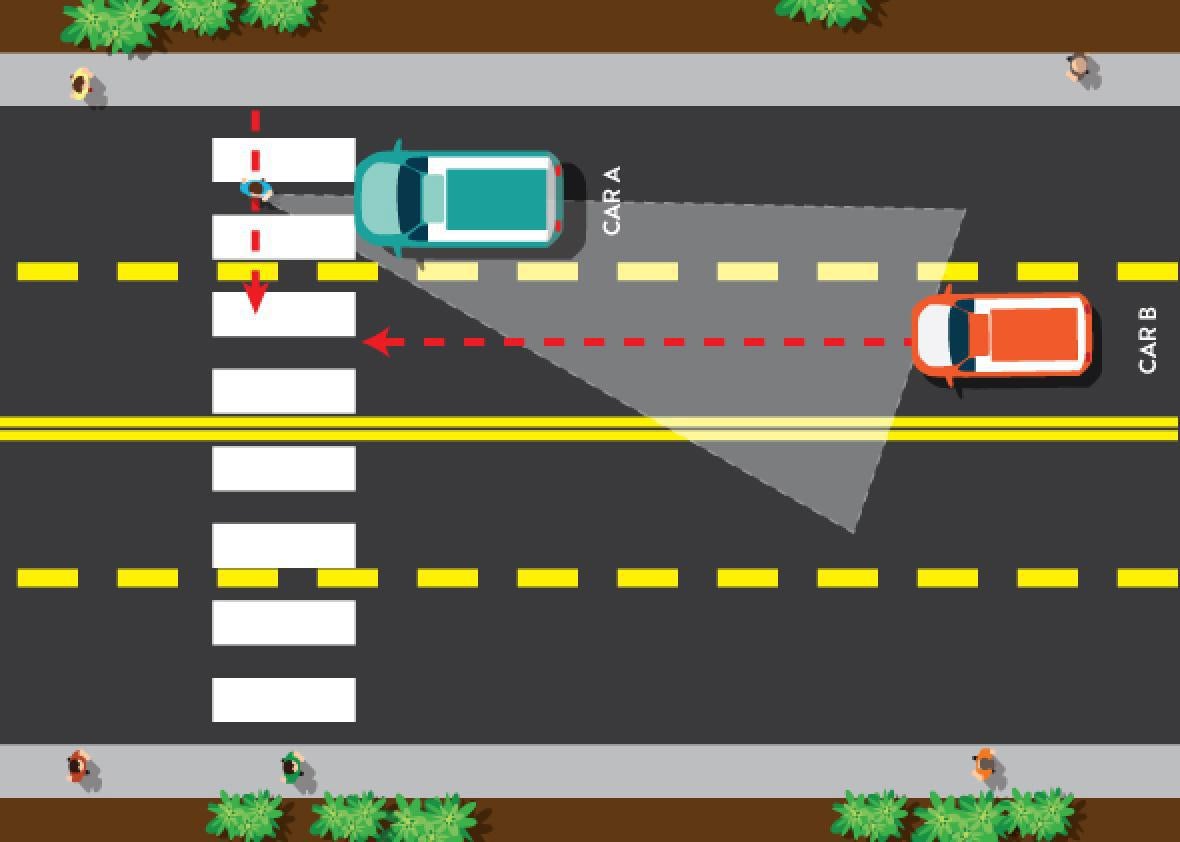

This situation—a motorist in one lane stopping for a pedestrian while those in other lanes may or may not—has a name: the multiple-threat pedestrian crash. Here’s how it happens. If Car A stops for me, his vehicle obscures both my view of Car B careening up next to him, and Car B’s view of me.

Slate staff with elements by iStock.

After a few too many near-misses for my tastes, I started getting grumpy with the nice drivers who stopped in the right lane. Your kindness is going to kill my damn kid, I would mutter to myself as I shook my head and smiled, and waved them across. Of course, then they’d wave me across. So then I’d scowl and wave them across. After about three minutes of this—punctuated by wild gesticulating in the direction of the other lane, what I hoped was the universal gesture for “moving fast”—eventually they’d grow irate. “GO!” some even yelled. “NO!” I’d yell. “It’s DANGEROUS!” At times it escalated enough that I was even tempted to exercise my favorite digit—to people who were just trying to be nice.

So what causes this ridiculous Oregon standoff? I spoke to Pam Fischer, a traffic safety expert who authored a 2015 report, Everyone Walks: Understanding and Addressing Pedestrian Safety, for the Governors Highway Safety Association. She reminded me that in some states, including Oregon, every intersection is a crosswalk, meaning that “if the pedestrian has put their feet into the crosswalk,” marked or unmarked, you, the driver “have to stop if you can.”

Drivers must at least yield to pedestrians in crosswalks in every state—even Missouri, I’ll have you know—but in Oregon, they must stop. So it’s likely that these drivers are just erring on the side of extra-courteous and assuming that once I venture out into the street, everyone else will stop for me because technically they have to. But that doesn’t mean everyone else will. After all, many Oregonians are originally from California, where a very light sprinkling of rain makes drivers lose all of their motor and cognitive skills. Others are no doubt hopped up on the legal marijuana. Maybe there’s a Ducks game. Maybe it’s Free Kombucha Day. It could be anything.

So if you’re a driver in the right lane of a multilane roadway, and you want to stop for a pedestrian, what can you do? Well, it helps if Car A stops well before the intersection, say, 20 feet, granting the pedestrian better visibility. But, warns Fischer, “laws can be confusing” when it comes to the Car B’s among us. “Whenever a vehicle is stopped in a marked or unmarked crosswalk and allowing a pedestrian to cross the roadways, the law usually says [other drivers] shall not overtake and pass that stopped vehicle.” But in states where a stop isn’t required for pedestrians, those Car B’s may feel they have the right of way, even if they don’t. (Or they might not see the pedestrian.)

And, given law enforcement’s general unwillingness to enforce any law protecting pedestrians in crosswalks, it’s no wonder the internet features a lot of video of cars blowing by people and a lot of wonder at where police priorities seem to be (ahem).

That generally leaves the onus on the shoulders (or feet) of yours truly and all of the other people who walk (or use mobility devices such as wheelchairs) by choice or necessity. Unfortunately, experts make it clear that I’m going about these crossings all wrong. The scowling wave-offs I precipitate don’t help in the long run, since they punish Car A’s for obeying the law. Instead, the experts tell me, pedestrians should walk carefully when beckoned but then stop in front of Car A and look around it. “Make sure that if there’s somebody coming, that somebody sees you,” says Fischer. “I wave my arm; I put that arm up in the air as I’m coming by that car.”

Kate Kraft, the executive director of America Walks, a national pedestrian advocacy umbrella organization, tells me she hopes for a shift in how motorists see pedestrians and in how pedestrians see themselves—as a large, diverse community who deserve safe passage. “We’re all pedestrians,” she reminds me. (Again, for lack of a better term, we mean pedestrian to include disabled individuals). “There is a growing urgency around this moral imperative that we stop killing pedestrians.”

Fischer also recommends “humanizing” every player on the road. “We like to put people into categories,” she admits. “Motorist, pedestrian, bicyclist. But we’re all people. People who walk, people who bike, people who drive. If we think about it as, that is my fellow man, I could be that person—this is a huge cultural shift.”

Sounds great. Until that happens, though, I’ll focus on what can keep me alive now: In most U.S. states, just because traffic is supposed to stop for me doesn’t mean it will. So I’m going to keep assuming they want nothing more than to splatter me across their grilles. Meanwhile, on the rare occasions I’m driving and I come upon a stopped car in the lane next to me, I’m going to slow down or stop until I see what’s going on. This way, I might live to see a world where motorists and pedestrians—sorry, people in cars and people on the sidewalk—live in harmony.