This article originally appeared on Inside Higher Ed.

“Were it so … that some little profit might be reaped (which God knows is very little) out of some of our playbooks, the benefit thereof will nothing near countervail the harm that the scandal will bring unto the library, when it shall be given out that we stuff it full of baggage [i.e., trashy] books.”

—Sir Thomas Bodley, founder of the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, explaining why he did not wish to keep English plays in his library (1612).

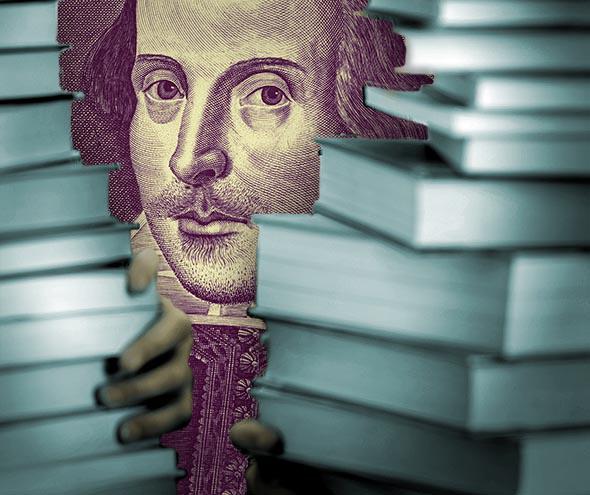

On William Shakespeare’s birthday this year, the American Council of Trustees and Alumni issued a report, “The Unkindest Cut: Shakespeare in Exile in 2015,” which warned that “less than 8 percent of the nation’s top universities require English majors to take even a single course that focuses on Shakespeare.” Warnings about the decline of a traditional literary canon are familiar from conservative academic organizations such as ACTA and the National Association of Scholars. What increasingly strikes me, however, is how frozen in amber these warnings are.

In a nation obsessed with career-specific and STEM education, there is scant support for humanities in general. Where are the conservative voices advocating for the place of English and the humanities in the university curriculum? One would think this advocacy natural for such academics and their allies. After all, when Matthew Arnold celebrated the “best that has been thought and known,” he was proposing cultural study not only as an antidote to political radicalism but also to a life reduced, by the people he called philistines, to industrial production and the consumption of goods.

We have our modern philistines. Where are our modern conservative voices to call them out? Instead, on the shrinking support for the liberal arts in American education—the most significant issue facing the humanities—organizations such as ACTA and NAS mistake a parochial struggle over particular authors and curricula for the full-throated defense of the humanities.

Worse, these organizations suggest that if one does not study Shakespeare or a small set of other writers in the traditional literary canon (moreover, in only certain ways), then literature and culture are not worth studying—hardly a way to advocate for literary studies.

The requirements at my own institution suggest how misleading the ACTA position is, and how thin a commitment to the humanities it represents. With no Shakespeare requirement in the George Mason University English department, it is true that some of our majors won’t study Shakespeare. However, because our majors must take a course in pre-1800 literature—nearly all the departments ACTA examined have a similar requirement—that means they’ll study Chaucer, or medieval intellectual history, or Wyatt, Sidney, Donne, Jonson, Milton, etc. (The study of Spenser, however, appears to me somewhat in decline; ACTA, if you want to take up the cause of The Faerie Queene, let me know.)

How can writers as great as these be off ACTA’s map? Is it because ACTA doesn’t really value them? Its Bardolatry is idolatry—the worship of the playwright as wooden sign rather than living being, a Shakespeare to scold with, but no devotion to the rich literary and cultural worlds of which Shakespeare was a part. Hence, too, the report maintains that a course such as Renaissance Sexualities is no substitute for what it calls the “seminal study of Shakespeare”—though certainly such a course might feature the Renaissance sonnet tradition, including Shakespeare’s important contribution to it, not to mention characters from Shakespeare’s plays such Romeo and Juliet or Rosalind and Ganymede.

ACTA also warns that rather than Shakespeare, English departments are “often encouraging instead trendy courses on popular culture.” This warning similarly indicates the narrowness of ACTA’s commitment to literary study. As anyone who’s ever taken a Shakespeare course should know, not only were Shakespeare’s plays popular culture in his own day (English plays were scandalous trash, thought Thomas Bodley), but also the very richness of Shakespeare’s literary achievement comes from his own embrace of multiple forms of culture. His sources are not just high-end Latin authors but also translations of pulpy Italian “novels,” English popular writers, folktales, histories and travelogues, among others. The plays remain vibrant today because Shakespeare allows all these sources to live and talk to one another.

Indeed, the literary scholars William Kerrigan and Gordon Braden point out that in this quality Shakespeare was typical of his age, for the vibrancy of the Renaissance derives in part from its hybridity. The classical was a point of departure, but neither Shakespeare nor Renaissance culture was slavishly neoclassical. Modern English departments, in their embrace of multiple literary cultures, in their serious study of our human expression, evince the same spirit.

Conservatives have suggested that the hybridity of the modern English major is responsible for declining interest in the major. That claim cannot be proved. Anecdotes and intuitions are insufficient to do so. Data on trends in the number of majors over time can only show correlation, not causation.

And in terms of correlation, here are four more likely drivers of the decline in the percentage of students majoring in English: students are worried about finding jobs and are being told (wrongly, according to the actual statistics) that the English major is not a path to one; students now have many new majors to choose from, many no longer in the liberal arts; English has traditionally had more female than male majors, and women now pursue majors, such as in business or STEM fields, from which they used to be discouraged (a good change); political leaders have abandoned the liberal arts in favor of STEM and career-specific education and are advising students to do the same (even President Obama jumped on this bandwagon, though he later apologized).

Regarding this last cause, the voices of organizations such as ACTA and NAS could particularly help, since many of these politicians are conservatives, and leaders of these academic organizations have ties to conservative political circles. In doing so, conservatives could help reclaim a legacy. In 1982, William Bennett, as chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities, urged colleges to support the humanities against “more career-oriented things.” By 1995, Bennett had become disgusted with what he saw as an overly progressive agenda in the humanities. Picking up his marbles and going home, Bennett urged Congress to defund the NEH. More recently, Bennett agreed with North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory that the goal of publicly funded education should be to get students jobs. “How many Ph.D.s in philosophy do I need to subsidize?” Bennett asked.

Shakespeare was generous in his reading and thinking. We can be, too. Literary scholars may disagree on many things—on the values to be derived from a particular literary work, on the ways it ought to be framed, on which literary works are most worthy of classroom reading. But such disagreements are just part of the study of the humanities in a democratic society. When we support the humanities, we support an important public space to have these disagreements. We also support Shakespeare—who really isn’t going away from the English curriculum—and the study of literature more generally.

The ACTA study, as far as I can tell, was mainly met with silence. That’s because the study is a rehash of an earlier one from 2007, itself a rehash of the culture wars of the 1980s and ’90s. No one cared, because most people have moved on from the culture wars, and for many of our political leaders, culture itself doesn’t much matter anymore. Culture wars have become a war on culture. In that battle, all lovers of literature should be on the same side. Advocating for the humanities, even as we argue about them, is walking and chewing gum.

We should be able to do both at the same time. I appeal to conservative academic organizations that we need to. The one-sided emphasis on majors that lead directly to careers and the blanket advocacy of STEM fields are far greater threats to the humanities than sustainability studies. And without the humanities, there is no institutionalized study of Toni Morrison. Or pulp fiction. Or Sidney. Or Shakespeare.