This article originally appeared in Inside Higher Ed.

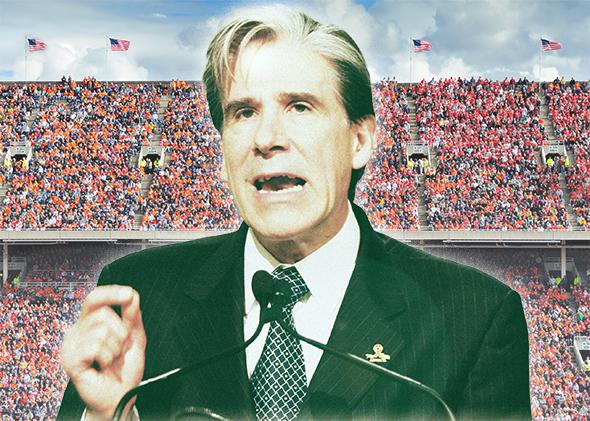

This week, the University of Miami tapped the dean of public health at Harvard and former minister of health for Mexico as its sixth president. In many ways the choice appears spot-on, during a time when Miami is trying to strengthen its medical program and expand its reach in Latin America. Yet when it comes to National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I sports—the arena in which Miami is perhaps best known, and not always favorably—the 61-year-old Julio Frenk will face a steep learning curve.

Frenk is far from alone. In an era when presidential search committees are placing increasing emphasis on the medical and technology fields, it’s not uncommon for a leader with limited experience with college athletics to take the helm of a Division I institution with a renowned sports legacy. And several of these new presidents have found themselves in the middle of sports controversies early in their tenures.

Miami’s own legacy is steeped in both success and scandal. Its football team won five national championships in 18 years but has gone through three coaches since its last title in the 2002 Rose Bowl. The basketball team has reached the NCAA Division I championship’s Sweet 16 round twice in the last two decades, most recently in 2013.

The Hurricanes have also endured multiple accusations of improperly rewarding football and basketball players, and the athletic program is still on probation following a two-and-a-half–year NCAA investigation into a former booster’s gifts to players. The football program has also been known at times for nationally televised brawls.

In the days since his appointment was announced, Frenk, a former soccer and basketball player who says he gained an appreciation of college athletics while a Ph.D. student at the University of Michigan, has limited his comments about Miami’s athletics program to statements of praise and his desire to learn. “I am, of course, very much aware of the important role that athletics play at the University of Miami, and I’m aware of the great record of its teams,” he said in an interview. “I look forward to learning more … I look forward to immersing myself in it.”

Frenk declined to go into specifics, but the methods by which presidents without experience in athletics immerse themselves in the athletic department of a university are worth exploring.

At the University of Michigan, a new president, Mark Schlissel, formerly a provost at Brown University, sparked controversy in the fall with comments he made about athletes’ academic performance in a public forum with faculty leaders. He said the Michigan football program admitted athletes who “aren’t as qualified” and can’t graduate. His remarks, reported in the student newspaper the Michigan Daily, prompted a next-day apology and came less than a month after the resignation of the university’s athletics director, who quit after the Wolverine football program came under scrutiny for placing a concussed football player back into a game despite his injury.

The list of sports powerhouses choosing presidents without experience with college athletics doesn’t stop at Michigan and Miami. The University of Oregon, another university that competes at the NCAA’s Bowl Championship Series level, announced on Tuesday that the dean of the University of Chicago law school would be its next president. Kent Syverud became president of Syracuse University in 2014 after serving as dean of the law school at Washington University in St. Louis. Florida state Sen. John Thrasher was named Florida State University’s president last fall. And Rutgers University appointed Robert Barchi, former leader of Thomas Jefferson University, a health sciences college, as president in 2012.

Yet most universities with large athletic programs choose candidates who have direct experience with college athletics. According to figures from the search firm Witt/Kieffer, 66 percent of presidents of universities that compete in the top tier of NCAA football have prior experience at a similar university, meaning they likely had some exposure to big-time athletics.

“There’s an awareness in these big schools that participate in big-time athletics that if their president has some familiarity with the NCAA, NCAA regulations, the financial aspect of these athletic programs and the public relations impact that these athletics programs can have on the institutions, the more attractive a candidate usually is,” said William Funk, head of a Texas-based search firm that specializes in higher education.

He continued: “Those institutions that deny they even think about it are just whistling in the dark. They better be thinking about it because a lot of money goes into this side of the house and it needs to be well-managed. If someone is completely naive about that side of the house, it can be troublesome down the road.”

At Syracuse, Syverud told faculty members in March that he’s been spending half his time dealing with the sports program in the wake of severe NCAA sanctions for awarding athletes improper benefits, academic misconduct, and a failure to enforce the university’s drug policy.

Presidents without experience in sports must quickly learn how to navigate the NCAA, communicate with athletics administrators, and mitigate scandals. When search boards choose an untested pick, they’re taking a risk. “I’ve really learned that this whole athletic sphere and the usual way you approach things just doesn’t work,” Schlissel told Michigan faculty, according to the Daily, adding later, “It’s a time-sink.”

Funk led the presidential search at Ohio State University last year. The university ultimately landed on Michael Drake, an ophthalmologist who was chancellor of the University of California–Irvine. Drake had experience in the medical field and in university administration, and while Irvine is not a large force in college athletics, Drake had been a member of the NCAA Division I Board of Directors.

Ohio State’s search committee wanted a leader who could advance the mission of the university’s medical and health science programs. The sports program, however, “wasn’t ignored” during the search process, Funk said. “They’re an athletic powerhouse and while it’s certainly not No. 1 or No. 2 or maybe even No. 3 on their list, it was always in the conversation,” Funk said. “They’re proud of that athletic program. They, like everyone else, have occasionally had issues they’ve had to deal with.”

As colleges search for presidents, concerns about research funding and the medical sciences are increasingly eclipsing concerns over athletic programs. “It used to be that if you had a strong athletic program, that was good, the state was happy with their university. That was how they evaluated the strength of the institution,” said Lucy Leske, managing partner of higher education practice for Witt/Kieffer. “Now, I think the public and Congress and even the president himself are suggesting, ‘Are these universities doing real good for the economy?’ ”

Greg Santore, practice leader for Witt/Kieffer’s sports leadership division, said because of increased scrutiny of athletic departments and a heightened call for transparency, it is becoming more necessary for presidents to have working relationships with the athletic director. Having coaches in place who understand that academics, not athletics, are the main priority of a university is also important, former Duke president Nannerl Keohane said.

“A really bad situation would be for someone to come into the university with an iconic coach who had been there a long time and was deeply respected but didn’t get it,” she said, adding that her positive relationship with Mike Krzyzewski, the legendary Blue Devils basketball coach, made her job a lot easier. “Of course there were a few tensions, but it was around the edges. It wasn’t core.”

Keohane, who left Duke in 2004, is now a professor of public affairs at Princeton University. When she was interviewed for the Duke post, the search committee was more interested in how she would lead the university’s medical enterprise than in how she would lead its athletic program.

But it didn’t take her long after arriving on campus to realize how deeply Duke’s athletic program is embedded into the university. She noticed immediately how prolific Blue Devils insignia are on Duke’s campus, whether on posters at employees’ desks or on the sweatshirts of students walking to class. Team pride brings a campus together, she said.

Yet pride can unravel into shame when athletic programs are poorly managed. “The challenges of a significant athletics program are complex and apparently getting more serious,” she continued. “When it works, athletics can be a very valuable part of an institution … But it can so easily go off the rails.”

Shortly after Keohane left the presidency, Duke was rocked by a high-profile scandal, when three lacrosse players were accused of rape, an accusation that was later shown to be false.

Outside of poaching a president from a similar institution, it’s difficult for colleges to tap a leader who fulfills an increasingly long list of desired qualifications. At the start of its presidential search, Miami published a profile for the position that listed 13 desired qualifications. “An appreciation for the complexities of college athletics in a major research university and a commitment to an unwavering sense of ethics and integrity in the oversight of athletic programs,” was seventh on that list, after qualifications like the ability to advance Miami’s academic agenda, research portfolio, and medical center.

“The job of a college president today, whether it’s at a small school or a large one, is so complex and demanding and it does require expertise in a variety of areas, athletics being one of them,” said Susan Resneck Pierce, a former college president who is the author of On Being Presidential and who coaches new presidents.

“I’m not sure you’re ever going to find a president who has expertise in all the areas,” she continued. “What I do think is you want to find somebody who knows how to quickly learn and seek and listen to advice.”

Isaac Prilleltensky, dean of education at Miami and a member of the 14-person presidential search committee, said Frenk is a good listener. “He will take the time to study in depth all the various aspects of the richness of the University of Miami, including athletics,” he said. “He will take the time to get to know all the aspects of the university equally.”

When pressed, Prilleltensky did not elaborate on the search committee’s consideration of Frenk in terms of the university’s athletic enterprise.

Miami’s current president, Donna Shalala, had been U.S. secretary of health and human services and chancellor of the University of Wisconsin–Madison before taking the job in Coral Gables. Before going to Wisconsin in the late 1980s, she was president of Hunter College and had little experience with Division I athletics. But it didn’t take her long to begin turning around the athletic program.

A year into her tenure at Wisconsin, she fired the football coach and brought in a new athletic director, who hired Barry Alvarez to reboot the football program. By 1993, the Badgers made it to the Rose Bowl, and Alvarez went on to coach until 2005. He’s now Wisconsin’s athletic director. Madison “was taking a chance I knew what I was doing,” Shalala told the Chicago Tribune in 1993. “But I had done my homework. I knew we could get first-rate coaches.”

In assuming the top spot at Miami, Frenk, not unlike his predecessor nearly three decades ago, inherits an imperfect athletics program. Frenk has said he looks forward to understanding more about Miami’s sports program. Similarly, people with an eye on Miami look forward to seeing how that future understanding becomes action.

“The first-time president who hasn’t had to deal with intercollegiate athletics,” explained Funk, who has placed more than 400 college presidents, “has to run really fast to catch up and become knowledgeable of the intercollegiate milieu and how to safeguard the institution [from] the excesses of the programs as well as take advantage of the programs.”