This post originally appeared on Inside Higher Ed.

A 7-month-old Facebook post about the conflict in Gaza, receiving attention only recently, has spurred a debate over hate speech at Connecticut College that has some students calling on the administration to condemn racist remarks.

Andrew Pessin, a professor of philosophy, says the students who accuse him of being a racist are deliberately misrepresenting words he used as a metaphor and that he was referring to Hamas, not all Palestinians. Students—in letters to the student newspaper and an online petition—say Pessin dehumanized Palestinians with offensive language.

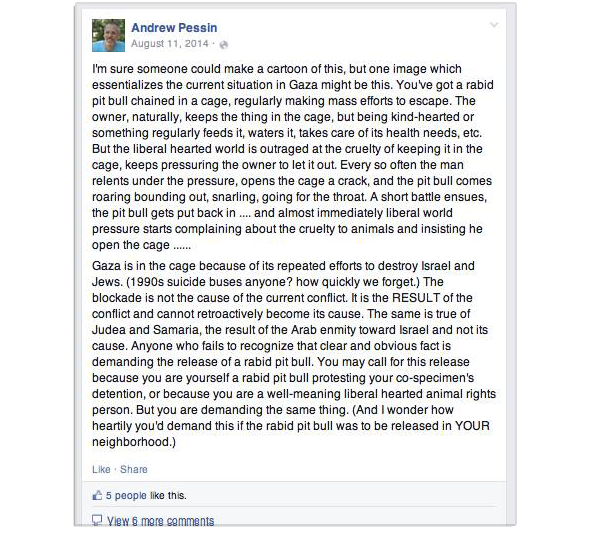

The post in question was written on Aug. 11, during the height of fighting between Israel and Hamas. In it, Pessin describes the situation in Gaza as one in which “a rabid pit bull is chained in a cage, regularly making mass efforts to escape.” In Gaza, according to the post, the conflict is a cycle of giving the dog a chance by letting it out of its cage, only to have to put the pit bull back in the cage when it snarls and goes for the owner’s throat.

Facebook screenshot courtesy of Inside Higher Ed

The student newspaper, the College Voice, published three letters this month from students and an alumnus who were outraged and repulsed by the post. The letters acknowledge that Pessin has a right to free speech. But they also call on the administration to make underrepresented students feel more comfortable by making it clear that the university doesn’t agree with Pessin’s views. How can the university support its diversity goals, the students ask, if it won’t call racist language what it is?

“Racism takes root when we have influential academics in our school who publicly express views of bigotry,” sophomore Lamiya Khandaker wrote in one of the letters. “Racism is accepted when the institution fails to address the responsibility of academics to watch what they say.”

Nowhere in the post does Pessin say “Palestinians,” but he also doesn’t say “Hamas.” In an interview with Inside Higher Ed, Pessin said he acknowledges that the post was ambiguous. He posted it after a series of 10 other comments written between July 23 and Aug. 11 about Hamas and the group’s tactics and goals.

Reading those preceding posts would have made it clearer that he was using the metaphor of a pit bull to describe Hamas, he said. “Let me say unequivocally: I am not a racist,” he said. “I am a passionate promoter of equal rights for all peoples. I’m a supporter of a two-state solution.”

When Khandaker emailed Pessin about the post in February, he apologized and said she misunderstood his intent. He deleted the post that day. Pessin thought that was the end of it, but a couple weeks later, he said the student newspaper published the letters without warning him. The letters appeared in the last edition before spring break began.

That ignited a firestorm without him having the opportunity to reply publicly, Pessin said. At first, Pessin thought it was just “sloppy college journalism” not to reach out to him for a comment. He wrote a brief letter to the editor in which—based on advice from the administration—he apologized for any hurt he caused. He wanted to defend himself, but he recognized that could put the blame on students who misinterpreted his words, he said.

Instead, the apology has been read as an admission of his guilt, he said. And now, he thinks publishing the letters without giving him a fair chance to explain himself was a part of a deliberate tactic to target him for his views. Pessin, who is Jewish, regularly writes and speaks out in support of Israel. “In my opinion, what this has become is not a matter of some students with hurt feelings, but it’s a fairly deliberate and drawn-out campaign to silence someone who openly advocates for Israel,” Pessin said.

The college newspaper’s editor in chief, Ayla Zuraw-Friedland, said she published the letters under the same policy that she always does—in the order they are received and without any editing. The paper published Pessin’s letter of apology online within 24 hours of receiving it, despite being on spring break, she said.

Zuraw-Friedland also was one of several people who co-wrote an online petition asking the administration to issue a statement saying the university doesn’t condone “Pessin’s racism and dehumanization.” “Dehumanization is a tool of racism,” the petition states. “Dehumanization has been used all throughout human history to justify genocide, colonialism and hatred of many communities.” The petition includes a photo of the Facebook post, though it only shows half of the post. Pessin feels that was a deliberate decision, too.

Students who are asking for the administration to speak out say that Pessin isn’t their target. His post was only a catalyst to address larger issues around diversity and how marginalized students can feel unsafe on campus when people in more powerful positions make biased remarks.

In her letter, Khandaker says that she took a class with Pessin and, as a Muslim, she never felt uncomfortable in class. But just because Pessin’s views don’t interfere in his teaching doesn’t mean they’re not a problem, she argues. In fact, because he is smart, influential, and well-liked in classes, students are more likely to listen to his posts on socio-political issues, she wrote. Khandaker is chair of diversity and equity for the student government, in which she’s responsible for bringing the concerns of underrepresented students to the administration.

Other students who criticized Pessin’s post said they did so to start a campuswide conversation about something they felt was important. “We call upon students, faculty and alumni to ask themselves: Is there a place for this language at Connecticut College?” wrote Michael Fratt and Kaitlyn Garbe. “We wonder ourselves how this particular situation would play out had this professor spoken out against Jews or L.G.B.T.Q. individuals.”

Fratt said in an interview Tuesday that his purpose in writing the letter was to encourage the campus to listen to the concerns of the students who were affected and hurt by Pessin’s post. Those students who have spoke out against Pessin’s comment have faced backlash and have been insulted on social media and Yik Yak, an app where users post anonymous comments. “I think most of the student body thinks Pessin should not be fired and this whole thing is students playing the offended card,” one post reads. “The majority should be louder than the whining bullies at this school.”

There also were several anti-Semitic comments made on campus and via Yik Yak after the letters were first published, Pessin said. He decided this week to take a medical leave of absence for the remainder of the semester, partially due to the stress the accusations against him have caused.

Later today, students, faculty, and staff will gather for a forum hosted by the administration on free speech, equity, and inclusion. In two campus emails announcing the forum, President Katherine Bergeron said the comments stemming from Pessin’s Facebook post have posed larger questions about the nature of free speech and the values of a diverse community. Connecticut College is a community that is aiming for “inclusive excellence,” she said.

“The conversations of the past few days—including some anonymous comments on Yik Yak—are evidence of how much work we have to do to reach our aspirations,” she said.