This article originally appeared in Inside Higher Ed.

Two months before the Civil War began, Noble Leslie DeVotie was boarding a steamship when he slipped, fell into the waters of Mobile Bay, and drowned.

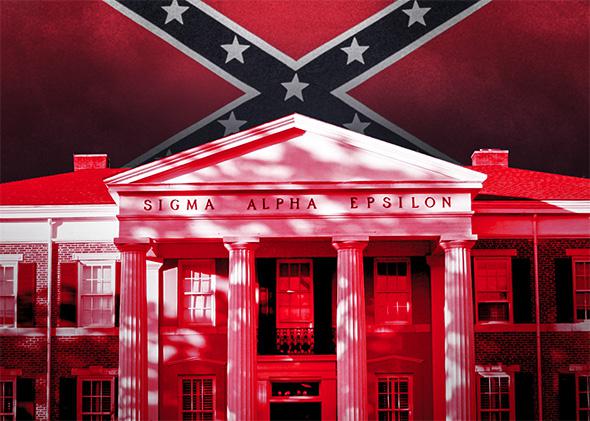

DeVotie was one of the founders of Sigma Alpha Epsilon, the only national fraternity founded in the antebellum South. A chaplain at Alabama’s Fort Morgan at the time of his death, he became the fraternity’s—and some argue, the country’s—first Civil War casualty. Nearly 75 other SAE members would die before the war’s end, the vast majority of them fighting for the Confederate South. When the survivors returned home, many found their universities burned to the ground and the 15 chapters of the fraternity in ruins.

SAE spent the next three decades rebuilding its ranks, eventually establishing chapters at Northern colleges. But their presence there among the well-established Northern fraternities was an uneasy one, so two members wrote a defiant march in which, as SAE’s manual describes it, the fraternity “entered, met and held at bay its rivals in the North.” It was the first of many songs SAE would produce, earning it the nickname “the singing fraternity.”

There’s nothing quaint about the nicknames SAE has these days—on many campuses people say the initials stand for “sexual assault expected” or “same assholes everywhere.” The fraternity is also known as the one in which members are most likely to die. And now it may be called the most racist.

A video that surfaced online Sunday showed members of the University of Oklahoma chapter singing a song that has managed to both “embarrass” the fraternity and echo its segregationist roots.

“There will never be a nigger at SAE,” the students sang to the tune of “If You’re Happy and You Know It” while dressed in formal attire and riding a bus. “You can hang him from a tree, but he’ll never sign with me. There will never be a nigger at SAE.”

The video of the song ignited a national furor this week, and both the university and SAE’s headquarters moved quickly to punish the chapter and distance themselves from what they hope will be seen as an isolated incident. But rather than depicting an anomaly, the video may be a rare, tangible piece of evidence of a much larger and persistent problem among America’s predominantly white fraternities.

“We have to remember that the Greek letter system in the United States was founded on pretty harsh and legally supported exclusionary practices,” Matthew Hughey, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Connecticut who studies the issue, said. “There’s a normal, mundane type of racism that functions every day, but it’s harder to see. We really shouldn’t be surprised at incidents like this when they get out, as they probably happen a lot behind closed doors.”

Despite the fact that its members agree to memorize and follow a creed known as the True Gentleman, SAE has frequently been accused of racist and discriminatory behavior over the years. Now the largest fraternity in the country, SAE seems to have played a disproportionate role in some of the most offensive incidents in recent decades, yet it remains a house in good standing at more than 200 campuses.

In 1982, the University of Cincinnati suspended its Sigma Alpha Epsilon chapter after it organized a racist party around Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday. According to an article in the New York Times, fliers for the event encouraged revelers to “bring such things as a canceled welfare check, ‘your father if you know who he is’ and ‘a radio bigger than your head.’ ”

In 1992, the Texas A&M University chapter hosted a “jungle fever”–themed party that, according to an online exhibit created by the university’s Cushing Library, featured “black face, grass skirts and ‘slave hunts.’ ” In 2000, members of SAE at Oglethorpe University were among men from four fraternities who threw bottles at black athletes and yelled racial slurs during a cross-country meet. In 2002, a member of the Syracuse University chapter of SAE wore black face out to local bars.

In 2006, two SAE students were suspended at the University of Memphis after harassing another member for dating a black woman and bringing her to the chapter’s house. In 2009, the Valdosta State University chapter caused outrage on campus after flying a Confederate flag on its front lawn. On Sunday, the Oklahoma State University chapter also drew ire on social media when a Confederate flag could be seen through one of its windows just hours after the controversy emerged at the University of Oklahoma.

In 2013, the Washington University in St. Louis chapter of SAE was suspended after some of its pledges were instructed to direct racial slurs at a group of black students. Last year, 15 SAE members at the University of Arizona broke into a historically Jewish off-campus fraternity and physically assaulted its members while yelling discriminatory comments at them. In December, Clemson University’s SAE chapter was suspended after the fraternity hosted a “cripmas” party at which students dressed up as gang members.

As for the now-infamous song, there’s evidence that the lyrics are not popular just among members of the Oklahoma chapter. One month ago, before the controversy at Oklahoma, a user on the online forum Reddit wrote that a nearly identical version was a “favorite” of SAE members at universities in Texas. On Monday, a Twitter user, whose profile has been made private, tweeted that he “was an SAE at a university in Texas from 2000-2004. The exact same chant was often used then. This is not isolated.”

Because the performance at Oklahoma was filmed—and because it so quickly spread across social media, thanks in part to aggressive efforts by the Oklahoma student activist group Unheard OU—both the university and SAE’s national headquarters issued swift responses. The national organization closed the chapter within hours of the video appearing online.

On Monday, SAE released a statement stressing that “Sigma Alpha Epsilon is not a racist, sexist or bigoted fraternity” and that it provides its members with anti-discrimination education and training.

“Several other incidents with chapters or members have been brought to the attention of the headquarters staff and leaders, and each of those instances will be investigated for further action,” SAE stated. “Some reports have alleged that the racist chant in the video is part of a Sigma Alpha Epsilon tradition, which is completely false. The fraternity has a number of songs that have been in existence for more than a century, but the chant is in no way endorsed by the organization nor part of any education whatsoever.”

On Monday, David Boren, the university’s president, ordered all members of the fraternity to leave the house by midnight on Tuesday. During a press conference, Boren said the university would not be offering the members housing assistance. “We don’t provide student services to bigots,” he said to applause, adding that he would like to see the students leave campus as soon as possible.

On Tuesday, the university expelled two fraternity members, Levi Pettit and Parker Rice, that they had identified in the video. Rice apologized for the incident, saying to the Dallas Morning News that he was “deeply sorry” for his “horrible mistake.” The incident and resulting investigation prompted intense soul-searching on the campus, which was ordered to desegregate nearly 70 years ago in a historic Supreme Court case that was a precursor to Brown v. Board of Education.

Unheard OU, the activist group that publicized the video, organized a large demonstration on Monday, and students took to social media to express their outrage and sadness. A football recruit who had committed to play at Oklahoma tweeted that he would no longer being doing so, and a current linebacker for Oklahoma, Eric Striker, sent a video through Snapchat furiously calling out members of SAE and other fraternities who cheer on black players when they’re on the field, only to sing racist songs behind their backs.

Boren on Monday said SAE will never return to Oklahoma while he remains president, prompting some to question online whether all universities should take similar, even proactive, stances against SAE, given such a pattern of discriminatory behavior among its chapters. “Just close all SAE chapters; they’re all horrible spawning areas,” one Twitter user wrote. Said another, “SAE proudly touts association to the Confederacy on its website. Close em all down.”

A detailed analysis of fraternity deaths by Bloomberg in 2013 found that SAE is the country’s deadliest, and it is often accused of promoting a culture that helps lead to campus sexual assault and hazing. Andrew Lohse, a former SAE fraternity member who famously went public about his experiences at Dartmouth College, said Monday that while his chapter never sang the lyrics from the Oklahoma video, it did set lyrics about violence against women to the same tune. Even though the chapter was in New Hampshire, Lohse added, several members still referred to the Civil War as “the War of Northern Aggression.”

Even so, Kevin Kruger, president of NASPA–Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education, said an outright national ban of an entire Greek organization remains unlikely. “I don’t think we’re at a place yet where SAE is branded as an organization that can’t get it right,” Kruger said. “But I think we are at a point where any organization that engages in this kind of behavior should start expecting zero tolerance.”

Benjamin Reese Jr., president of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education and the vice president of institutional equity at Duke University, said he is also not in favor of simply banning all chapters belonging to a specific fraternity. While the incident at Oklahoma is especially painful, Reese said, he still believes that fraternities can be educated and their policies changed to foster more inclusion.

“There are certainly fraternities that are deeply engaged, but also many that operate in a similar way to how they operated half a century ago,” Reese said. “But I would shy away from painting all fraternities with a broad brush. We are academic institutions and we provide education for lots of other things. This is an area where perhaps we haven’t done as good a job.”

Hughey, however, warned against placing the blame for this kind of behavior on “some bad apples.” It’s a problem, he said, that is not unique to a few members of SAE.

“The Greek letter system is talked about as though it’s full of good, upstanding young gentleman and then there’s these bad apples that are unique,” Hughey said. “While that may be true at some chapters, it turns the conversation into a matter of good versus bad, and ignores all the ugly that surrounds the whole system.”