This article originally appeared in Inside Higher Ed.

A debate about a Confederate flag two students put up in their dorm room at Bryn Mawr College has escalated to a demonstration involving hundreds and a broader debate about diversity and inclusiveness at the institution. Those students who donned black and held homemade signs in the protest after the flag incident want it known that they’re not finished yet.

Many minority students feel that their voices aren’t valued or highlighted on campus, and they want the college to acknowledge their concerns, said Allegra Massaro, a senior and president of the Tri-College Chapter of the NAACP. “These issues are not limited to Bryn Mawr’s campus,” Massaro said. “They exist for students of color at a lot of elite universities.”

In response, the administration has written a series of community letters, and last week, President Kimberly Cassidy pledged that change would come, starting with recreating a diversity council to focus on handling issues of bias and re-examining how the college’s honor code can better address them. Cassidy told Inside Higher Ed that it was frustrating to watch Bryn Mawr’s minority students go through such a painful experience and that college leaders shared their goals. “I don’t see what the students are asking about as demands,” she said. “In terms of what they’re looking to do, those are the very same things that we’re looking to do.”

The Flag Controversy

In September, two Bryn Mawr students hung up a Confederate flag in a public area of the Radnor Hall dormitory and used neon duct tape to symbolize the Mason-Dixon line on the carpet. Others in the dorm asked the students to take the flag down, but they refused, saying it was a representation of their Southern pride. After more requests from students and dorm leaders, the flag was moved inside their room, but it was still visible through a window.

The administration had to balance the calls for action from some students and the rights of the students who hung the flag, Cassidy said. Bryn Mawr also has a strong tradition of self-governance among students, and that process can take time. Eventually, the students, who haven’t been publicly identified, took down the flag. It is unclear to what extent the students felt pressured to do so, and they have made no public statement. “I think some people felt like that took too long,” Cassidy said.

In the days that followed, campus was chaotic, Massaro said. Some students went home for a few days. Other upset students were searching for a way to show their anger, many suggesting that Cassidy’s inauguration on Sept. 20 would present an ideal opportunity. By midweek, Interim Provost Mary Osirim sent an email asking faculty members to be patient with students who might be missing class or turning in assignments late due to the “great deal of stress” caused by the flag and related issues of race on campus. “So now you have this incident and these people’s freedom of speech disrupting the whole purpose of the college,” Massaro said.

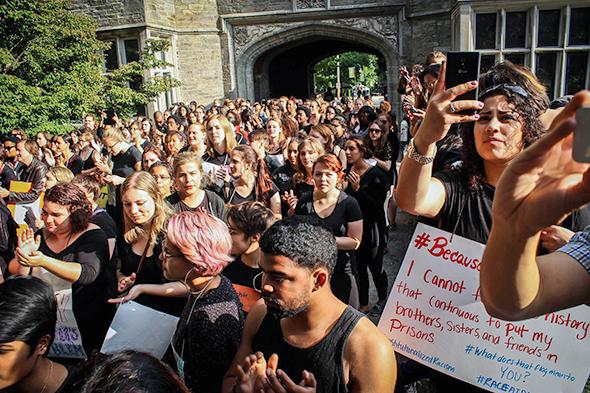

By the end of the week, student leaders organized a demonstration, in which more than 500 students, administrators, faculty members, alumnae, and trustees participated and made a human chain around one of the main buildings on campus. “It was a terrific way that the students organized it to be a demonstration of larger systemic issues, not only on Bryn Mawr’s campus in but in society as a whole, to give voice to marginalized groups,” Cassidy said.

The campus NAACP chapter, which organized the event, provided a list of changes it wants to see on campus, based on student input. Some were specific and immediate: that the Confederate flag be banned from campus, that the college’s Honor Code be updated to have a section dedicated to “Race Respect,” and that the students who hung the flag offer a public apology to the campus and face consequences from the athletic department (both are members of multiple sports teams).

Several people who’ve commented on the issues online have defended the two students, saying displaying the flag is their right. Cassidy said she could not comment on any disciplinary actions the two students may face but said the college is still in the process of handling the situation.

Other changes the student demonstrators are pressing for are more long-term, such as mandatory diversity training for all students and faculty, increasing the number of faculty of color, and offering more education about race symbols. Cassidy also mentioned diversity training and increasing the number of faculty of color as steps the administration is already working on.

Like a recent protest over race at Colgate University, this movement spread on social media, where students and alumnae shared their personal stories with hashtags such as #ifiwere, #becauseiam, and #raceatBMC. (Students at the two colleges also supported each other’s movements via social media.)

Issues Beyond the Flag

Debates over displaying Confederate flags on campus aren’t uncommon. But they’re more often seen at Southern colleges in states where Confederate culture was historically associated with the institution—as opposed to a women’s liberal arts college outside Philadelphia that prides itself on being progressive.

Regardless, while the flag controversy may be the topic of the moment, students who are upset maintain that the action—and more importantly, the administration’s reaction—is representative of an ingrained culture of marginalization and racism.

Bryn Mawr has roughly 1,300 undergraduate students. About 37 percent of those students are white. Black and mixed race students each represent about 5 percent, and Asian and Latina make up roughly 10 percent each. Another 23 percent are listed as nonresident aliens and 10 percent as unknown. The college prides itself on being a majority minority campus. But when those groups don’t feel comfortable or valued on campus, statistics don’t mean anything beyond an admissions selling point, an ability to market a diverse climate, Massaro said. “Colleges work really hard to get their numbers up there,” she said. “But then when those students are here, what are you doing to make them feel comfortable? And Bryn Mawr’s not doing much.”

Some participants at the demonstration referenced a variety of incidents over the last several years. One was the closing of the Perry House, a black cultural center that also housed other students of color. It closed a few years ago due to lack of maintenance, upsetting residents who thought the college had let the building fall into disrepair. A new section of the renovated Haffner Hall will house Perry House when it opens next year.

Another incident that upset students and faculty occurred last year, when a student made a flier of an African man running through the plains and being chased by an ostrich. Copies of the flier were taped to the door of a professor from the Congo. The incident led to the town hall meeting, where students voiced similar concerns to those expressed in the past few weeks. There were no immediate changes, and it was unclear what sort of punishment, if any, the student faced, Massaro said.

That was a common thread among the online discussion of the flag incident and demonstration—exasperation that changes haven’t been made even though problems have been raised before. “Time after time the administration hasn’t taken a firm stance on it,” Massaro said. “They’ve been rather passive or neutral.”

Students are hopeful that having a new president will help in effecting change, Massaro said. Part of the issue is that there seems to be confusion about who’s responsible for overseeing issues of diversity and inclusion. One option could be to hire a social responsibility or diversity officer to oversee that, she said.

Creating a more inclusive environment takes time, though, and it requires broad participation across the campus, Cassidy said. That’s difficult since new groups of students are brought in each year, so there has to be ongoing education about how to support a diversity of thoughts and experiences without offending others.

“We have all the action ahead of us,” Cassidy said. “But [the demonstration] felt like a concrete step forward. I don’t want to suggest that everything’s fine now. It’s a process, and we’re working on it.”