This article originally appeared in Inside Higher Ed.

When the sexual assault prevention group Culture of Respect attended the Dartmouth Summit on Sexual Assault in July to promote its forthcoming website, the group went by a different name. The nonprofit passed out business cards and marketing all emblazoned with the phrase “No Means No.”

For the last two decades, that’s been the slogan of choice for sexual assault prevention efforts, and just a few months ago it seemed like a perfect fit for the new organization. But in the weeks leading up to No Means No’s official launch, the organization began having second thoughts.

“The swiftly evolving conversation about defining sexual assault signaled to us that we needed to reframe our name as something more positive,” said Allison Korman, the group’s executive director. “And it’s even possible that ‘No means no’ will be an outdated or irrelevant concept in 10 years. Students may not have even heard of the phrase by then.”

That’s because at a growing number of colleges, “No means no” is out, and “Yes means yes” is in. And it’s more than just revising an old slogan—from coast to coast, colleges are rethinking how they define consent on their campuses.

Last month, California Gov. Jerry Brown, a Democrat, signed legislation requiring colleges in the state to adopt sexual assault policies that shifted the burden of proof in campus sexual assault cases from those accusing to the accused. Consent is now “an affirmative, unambiguous, and conscious decision by each participant to engage in mutually agreed-upon sexual activity.” The consent has to be “ongoing” throughout any sexual encounter.

On California campuses, consent is no longer a matter of not struggling or not saying no. If the student initiating the sexual encounter doesn’t receive an enthusiastic “yes,” either verbally or physically, then there is no consent. If the student is incapacitated due to drugs or alcohol, there is no consent.

California is the first state to make such a definition of consent law, but other states may soon follow suit. In New Hampshire and New Jersey, state legislators have introduced bills that would also link state funding for colleges to their definition of sexual assault, requiring the use of affirmative consent. In New York, Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, plans on proposing legislation that would require a uniform definition of consent similar to California’s to be used for all of the state’s private colleges.

Earlier this month, the State University of New York system adopted that same uniform definition at all of its 64 campuses. The California State University System adopted its new definition months ago. Every Ivy League institution except Harvard University has adopted some form of affirmative consent. According to the National Center for Higher Education Risk Management, more than 800 colleges and universities now use some type of affirmative consent definition in their sexual assault policies.

“There’s quite a surge in support of a ‘Yes means yes’ formula,” said Ada Meloy, general counsel for the American Council on Education. “It’s certainly an ongoing movement, and is likely to be a generally positive thing. At the same time, it’s not easy to develop a good definition of affirmative consent. We wouldn’t want a one-size-fits-all approach for a variety of institutions.”

Moving From “No Means No”

Victims’ rights advocates continue to praise the idea of affirmative consent and the momentum the concept has recently gained. Laura Dunn, executive director of SurvJustice, said campus sexual assault policies could even “fill in some of the holes” in criminal laws regarding consent. In many states, consent is still based on a victim verbally or physically resisting, even as colleges within those states adopt affirmative consent policies.

Because colleges use a lesser burden of proof than criminal courts—preponderance of evidence rather than beyond a reasonable doubt—it makes sense to have a different definition of consent on campus, Dunn said, though she would ultimately like to see states adopt similar definitions at the criminal level as well. In order to comply with Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, colleges must investigate complaints of sexual assault, even if students decline to go to the police.

“Traditionally we’ve focused on a lack of consent as someone fighting off an attacker,” Dunn said. “You looked for evidence of resistance. We only talked about what consent was not, which is not a very helpful paradigm. From the victims’ side, it says we have to resist. But even looking at this from the perspective of someone being accused, the traditional definition is telling them that it’s O.K. to do this until the victim says ‘no.’ That’s not really a helpful definition for them either because it can really be too late at that point. With affirmative consent, it’s simple. Consent is consent.”

“No means no” hasn’t always had such a negative connotation. The Canadian Federation of Students popularized the phrase as part of a well received, and still ongoing, sexual assault awareness campaign it launched in 1992. The group even owns the trademark in Canada, wielding it to stop the production of clothing and other merchandise that make light of the phrase (like a 2007 t-shirt that said “NO means have aNOther drink”). The same year the campaign was launched, the Canadian government adopted affirmative consent as the country’s legal standard, making “No means no” just a slogan, not a binding definition of consent.

The slogan has become well known in the United States as well, though over time some college students began to use it as fodder for offensive jokes. A Yale University fraternity was suspended for five years in 2011 after its members marched around campus chanting “No Means Yes, Yes Means Anal” during a pledge initiation event. Just last week, a fraternity at Texas Tech University was stripped of its charter after painting the same phrase on signs during a party.

Unlike Canada, “No means no” is both a slogan and, in some states, the definition of consent. While there were efforts to create a uniform affirmative consent definition for all colleges during the recent reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act, they were not successful. Meloy, of ACE, said she’s supportive of affirmative consent but believes that the final definition of what that phrase means should be left up to individual campuses or college systems. “I think institutions’ governing boards are the place for this to be discussed and considered,” she said.

But it’s that lack of a standard definition for affirmative consent that has led some colleges like Harvard not to adopt it.

Harvard’s policy forbids what it calls “unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature,” stating that “conduct is unwelcome if a person did not request or invite it and regarded the unrequested or uninvited conduct as undesirable or offensive.” Earlier this week, 28 current and former Harvard law professors said the policy could deny due process to those who are accused and that its definition of unwanted conduct was too broad and vague. Student activists, meanwhile, said the definition doesn’t go nearly far enough, and urged Harvard to change its definition to one of affirmative consent, saying in a petition that “the absence of a ‘no’ does not mean ‘yes,’ and our university policy should explicitly recognize that.”

Mia Karvonides, the university’s Title IX officer, said that Harvard uses a standard that is “consistent with the standard in all federal civil rights laws that apply in an education setting,” and that even its peers in the Ivy League don’t truly use an affirmative consent standard as they don’t require a verbal yes at every turn

“The closest any college comes to a defined affirmative-consent approach is Antioch College,” Karvonides said. “Under their policy, consent is given step by step at every point of engagement during an intimate encounter. You must verbally ask and verbally get an answer for every point of engagement. ‘May I kiss you? May I undo your blouse?’ ”

“An Absurd Policy”

When the Antioch approach was introduced in 1991, it was widely mocked, including in a Saturday Night Live sketch, for what some saw as reducing a sexual encounter to a series of robotic yes and no questions. That critique of affirmative consent has been renewed in recent months as more colleges began to adopt similar policies. John Banzhaf, a law professor at George Washington University, said, the idea that students would ask for permission at every point of a sexual encounter is “unreasonable.”

“It just isn’t the way things work,” Banzhaf said. “How would this work in practice? Suppose the guy asks, ‘May I touch your breast?’ Does that mean through her shirt? Over her bra? Does that mean he can touch her bare breast? Does it mean he can touch it with his hand or his lips? What if this all happens in succession? As things escalate, is he supposed to ask before each of the 20, 30, 40 steps? Nobody talks like that, not even lawyers.”

Earlier this month, anti-sexism group UltraViolet tried to illustrate that affirmative consent can be natural and sexy by releasing an online video ad that mimicked retro pornography. In the purposefully grainy clip, a college-aged pizza delivery boy brings an unwanted pizza to a young woman’s apartment. When the man apologizes for his mistake and refuses to force the pizza on her, she finds his seeking of consent attractive and one consensual act leads to another. As the couple moves from kissing, to lying on top of one another, to removing their clothing, they often pause to quickly—breathlessly—ask “Is this OK?”

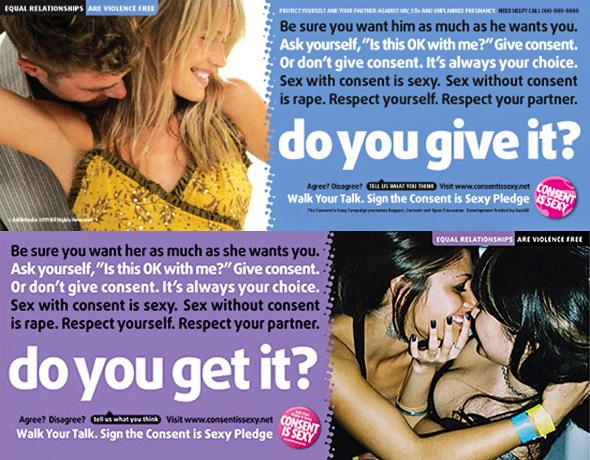

The Consent Is Sexy Campaign offers campuses a series of posters making the same point, and some institutions have established campaigns of their own to explain why asking for consent is not a mood-killer.

Others are not so concerned with whether affirmative consent policies are awkward or un-sexy, but whether they’re dangerous and unjust. In a position paper, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education argued that there is “no practical, fair, or consistent” way for colleges to ensure an affirmative consent standard was followed. “It is impracticable for the government to require students to obtain affirmative consent at each stage of a physical encounter, and to later prove that attainment in a campus hearing,” FIRE stated.

Furthermore, most campus policies state that yes does not mean yes if a student is intoxicated. At Cornell University, for example, a student cannot consent if he or she is highly intoxicated. At the same time, if the accused is also highly intoxicated, he or she cannot use intoxication as a defense. In the case of two intoxicated students, Cornell’s rules place the responsibility on obtaining consent with whichever student is the “initiator of further sexual activity,” saying that “the inability to perceive capacity does not excuse the behavior of the person who begins the sexual interaction or tries to take it to another level.”

“It’s an absurd policy,” Joe Cohn, FIRE’s legislation and policy director, said. “How can the dean of the English department or a physics professor or whoever else is on the panel at a hearing know who was the initiator and who was not? What it really means is that if someone accuses another student of sexual assault in a situation like this, then the student who did not do the accusing is immediately considered to be the one responsible for initiating the conduct.”

Banzhaf said switching to a “Yes means yes” standard that includes nonverbal cues only adds more ambiguity to obtaining consent. What colleges and states should actually focus on, he said, is removing any remaining ambiguity around “No means no.”

“I don’t think the problem is the definition of consent,” Banzhaf said. “The problem is that too many guys simply don’t take no as no. They’re either drunk or stupid or have been conditioned by our society to believe that no means maybe and that if they keep pressing that no may turn into a yes. In most states still, for it to be rape, the guy must use force or threat of force or the woman must be totally incapacitated. That’s what needs to change. We have to have a unified understanding of consent and that should simply be that no really means no.”