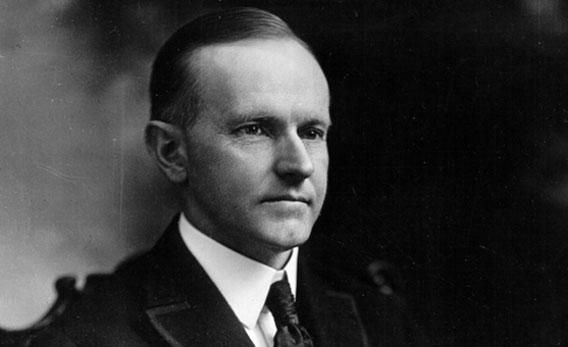

This week, Michele Bachmann was asked which presidential faces she would carve into Mount Rushmore if she could. First she said Ronald Reagan—no surprise there. But then, in a comment that has provoked titters, she named Calvin Coolidge.

Bachmann’s choice wasn’t as silly as it sounded. In fact, anyone paying attention to Coolidge’s posthumous fortunes—admittedly, a small group of us—wouldn’t find anything peculiar about Bachmann’s reply. Coolidge has long been a hero to American conservatives.

While historians have in recent years written countless books about the rise of Reaganism, almost all these works begin in the 1950s or 1960s, with figures like William F. Buckley and Barry Goldwater. This chronology wrongly omits Coolidge. Indeed, to understand the Republicans’ recent hostility to long-established liberal programs and ideas—from Social Security and collective bargaining to Keynesianism and financial regulation—it helps to return to Coolidge and the pre-New Deal roots of today’s anti-tax, anti-government conservatism.

Michele Bachmann’s admiration for Silent Cal is close to an article of faith on the right today. Last fall, Sarah Palin, in her book America by Heart, repeatedly praised an address that he gave on the 150th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence—a fairly generic piece of ritual, patriotic speechmaking, albeit rendered in Coolidge’s customarily clean prose. This summer a columnist for the ultraconservative Washington Times credited the Coolidge income tax cuts—particularly his lowering of the top marginal rate—with bringing in additional revenue and promoting growth. Amity Shlaes, a right-wing journalist-cum-amateur-economist and author of a book attacking the New Deal, is now writing a Coolidge biography that reportedly will seek to boost his reputation, which hovers somewhere between mediocre and dismal.* (For my own interpretation, see my book Calvin Coolidge.)

Nor do these Tea Partiers represent a new trend. The Coolidge cult is now going on 30 years. Ronald Reagan can be said to have launched it back in 1981 when, upon entering the White House, he removed Harry Truman’s portrait from the wall and hung up Coolidge’s. Reagan also hosted at the White House an obscure (now deceased) historian named Thomas Silver. Silver’s magnum opus, Coolidge and the Historians, labored to show how mainstream scholars—who had generally depicted Coolidge as an undistinguished chief executive smiling upon the prosperity of the 1920s, indifferent to the economic problems rumbling beneath the surface that erupted in the Great Depression—had gotten Cal’s legacy all wrong. At the time, this Coolidge boomlet on the right was evident to astute observers. On July 4, 1981—Coolidge’s birthday—the historian Alan Brinkley published in the New York Times an op-ed piece titled “Calvin Reagan,” demonstrating that it was Coolidge to whom Reagan turned as his “political patron saint.”

Like Reagan, Coolidge believed in small government, cutting taxes, deregulation, public piety, and the principle that for government to assist business would benefit the economy as a whole. Like Reagan, he held that government should regulate lightly, trusting in the civic-mindedness of business leaders and expecting that productivity and prosperity would shower their bounty on everyone. Even Reagan’s firing of the air-traffic controllers in 1981—an assertion that the executive could decide when the public interest did or didn’t need to take precedence workers’ rights—drew inspiration from Coolidge’s decision as governor of Massachusetts in 1919 to fire striking police officers.

Reagan’s admiration for Coolidge trickled down to the G.O.P. establishment. The consultant Roger Stone, last seen taking credit for Eliot Spitzer’s downfall amid his prostitution scandal, used to hold July 4 birthday parties in Coolidge’s honor. Robert Novak called Coolidge his second favorite president—following Reagan. The period even had its own pro-Coolidge revisionist biography, Robert Sobel’s Coolidge: An American Enigma.

Perhaps the most important Coolidge booster of the 1980s (besides Reagan) was Jude Wanniski, the Wall Street Journal editorialist who popularized supply-side economics. Wanniski believed that Reagan subscribed to supply-side notions because he hadn’t been schooled in the Keynesian thought that pervaded the academy after World War II. Reagan, in other words, was a child of the Coolidge era. Along with his Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, Coolidge insisted that lower tax rates on the wealthy would yield increased prosperity and revenue. Wanniski called a talk that Coolidge gave to the National Republican Club in New York City “the most lucid articulation of the [supply-side] wedge model by a politician in modern times.”

Today’s Republicans are therefore correct to take Calvin Coolidge seriously—more seriously than the cartoonish stereotypes that have come down through history. His pre-New Deal, pre-Keynesian macroecnomic ideas and policies are precisely what they’d like to reinstitute. Ultimately, however, the conservative regard for Coolidge isn’t a credible, serious historical interpretation; it’s an ideological interpretation, motivated by present-day political purposes more than any desire to understand his own life, times, and legacy.

For the right, the fact that Coolidge presided over sustained growth—and without accumulating massive debt, as Reagan did—seems to ratify the wisdom of the low taxes, loose regulation, and limited government that they still champion. As for the Depression, they find it easier to scapegoat Herbert Hoover—almost certainly the worst president of the 20th century next to Richard Nixon—than to admit to blots on Coolidge’s legacy.

This view is problematic for many reasons, not least because it assumes that presidents neither benefit from the achievements of their predecessors nor bear responsibility for the long-term consequences of their own policies. Coolidge in fact benefited from the wartime spending under Wilson, which buoyed the economy into the 1920s. And while he can’t shoulder all the blame for the Depression, in retrospect many errors of his economics became painfully clear.

Although the economy boomed in the 1920s, wealth grew unevenly. According to a 1928 Brookings Institution report, more than one-half of American families remained near or below subsistence at the time—despite an economic boom that was dubbed the “Coolidge Prosperity.”This maldistribution of wealth—in some ways similar to today’s—meant that while business was able to produce record numbers of cars, radios, and appliances, many citizens were hard-pressed to buy them. In 1927, the popular economists William Foster and Waddill Catchings published Business Without a Buyer, arguing that supply did not in fact create its own demand, and that overproduction could be dangerous. Coolidge’s fiscal policy failed to correct these imbalances.

What was more, despite warnings from economists such as William Z. Ripley, Coolidge declined to restrain the Wall Street speculation that flourished in the late 1920s. One problem was margin trading—buying stocks with a tiny down payment and a loan from your broker for the rest, then selling them at a profit soon after. Like Charles Ponzi’s notorious scheme, margin trading depended on the buyer not getting caught short when the bill came due. Some urged the Federal Reserve to stop lending brokers money to enable these deals, but Coolidge kept mum. Even in January 1928, when brokers’ loans reached an untenable volume, the president denied they were out of control. His administration also declined to regulate the market in other ways, permitting, for example, the sale of stocks back and forth between brokers to drive up shares and fool unwitting lay investors.

One can also call into question Coolidge’s policies regarding agriculture, global trade and credit, anti-trust enforcement, and other issues. To what degree different policies could have averted the catastrophe of the 1930s is unknowable. But Coolidge’s naive faith in the gospel of productivity and the benevolence of business deterred him from even asking the questions that might have mitigated the misfortune.

The Depression buried Coolidge’s economics. The success of the New Deal sealed the coffin, seemingly forever. But Reagan’s legions have labored hard to bring them back from the dead, and as memories have faded and historical knowledge atrophied, their arguments have gained adherents—to the point where they now go unquestioned in many precincts of the right.

Correction, Nov. 15, 2011: This article originally misspelled the last name of Amity Shlaes. (Return to the current sentence.)