I.

The liberal establishment’s third and perhaps biggest blunder in dealing with the legacy of Jim Crow isn’t tied to the failings of any one particular program, like busing or affirmative action. It’s a systematic problem, one rooted deep in the dysfunctional relationship between black America and the American left.

I first recognized this particular issue while researching racial integration in the advertising industry, which—as Mad Men viewers can attest—was far from a rousing success. The industry today is only marginally better than it was in Don Draper’s era. Starting in 1999, I spent eight years in advertising, working at five different agencies, and I can count the black people I worked with on one hand. The industry’s racial disparities are so bad that in 2008, the NAACP announced something it called the Madison Avenue Project, a full-court legal assault on the industry to improve its hiring, promotion, and retention of minority professionals. Cyrus Mehri, the civil rights attorney best known for crafting the NFL’s famous “Rooney Rule,” signed on to help lead the crusade. In its story on the launch of the Madison Avenue Project, USA Today called advertising “a poster child for the death of diversity.” Mehri and the NAACP cited a wide range of culprits for this state of affairs—everything from bias in HR policies to broader socioeconomic barriers that keep lower-income minority hires from getting within a mile of the industry’s front door—but they left out one of the most obvious ones: the persistence of a separate and unequal black advertising industry, sanctioned and sponsored by the U.S. government. It’s harder to bring minority talent in when minority talent is being paid to stay out.

Photo courtesy Nixon Presidential Library

In 1969, when the Nixon administration launched its flotilla of affirmative-action programs, one of the president’s signature efforts was the Office of Minority Business Enterprise, which made small-business loans available to black- and Hispanic-owned businesses, created vehicles for private equity groups to invest in those businesses, and carved out quotas and set-asides in federal procurement contracts to support them. White-owned companies that bid on government projects—for an ad campaign for military recruiting, for example—were now required to subcontract a certain percentage of their business to black-owned companies, in the interest of sharing the pie. Thanks to the efforts of Reverend Jesse Jackson and Operation PUSH, this practice soon evolved beyond mere legal obligation to become a standard tactic for good racial PR. Black-owned Ford dealerships, black-owned McDonald’s franchises, black-owned Coke distributors, all followed from the drive to bolster black ownership and entrepreneurship. During the ’70s and ’80s, this policy allowed black-owned ad agencies not only to survive but to create a parallel industry of their own, earning hundreds of millions of dollars and bolstering the black media landscape of Ebony, BET, and urban radio.

But the result of these set-asides was two forms of affirmative action working against each other. Here’s how it played out in advertising: Under government and public duress to integrate their workforces, white agencies (or “general market” agencies, as they’re often called) launched a wave of minority hiring that had an immediate impact, taking the rate of black employment in the industry from a rate of practically zero in 1965 to 3.5 percent in 1970. However, since those same white agencies were now required to subcontract projects out the door to minority agencies, their incentive to bring black hires in was significantly diminished. The rationale that black agencies used to justify their business model was that they were more qualified to speak to black consumers, which in turn cemented the stereotype that white people were more qualified to speak to white consumers. Culturally, legally, and economically, the industry settled into a pattern which ensured that “white” advertising happened over here and “black” advertising happened over there. White agencies did little more than token hiring and recruiting.

Photo by Jerome Delay/AFP/Getty Images

Meanwhile, the few black hires who did make it in the door at white agencies now had a very strong incentive to turn around and walk back out to a black agency, because that’s where the short-term benefits were. Life at a black agency offered decent money, a likelier shot at promotion, and a chance to join in the Black Pride movement that was taking hold in the 1970s. By the mid-1980s, black employment at general market agencies fell from 3.5 percent back to 1.7 percent, with high-profile black defectors frequently leaving white firms to hang out their own shingles on the other side of the color line. Which might have been an acceptable outcome had the black agencies flourished and become a thriving industry of their own. They didn’t. In 2000, the top 20 black-owned ad agencies combined accounted for 0.5 percent of total industry revenues. Integration on Madison Avenue failed. Black solidarity and empowerment failed as well. In trying to split the difference between the two, we wound up with neither.

It’s clear that minority contracting laws, which are still very much in force, have a countervailing effect on minority hiring at general market firms. At a time when blacks in advertising need a policy to help them move up, what they have instead is a policy that encourages them to walk out. So if you want more “diversity” in general-market agencies, pretty high up on your to-do list should be a trip down to Washington, D.C., to eliminate the set-aside programs that keep black agencies and black talent marooned in their own corner of the industry. Yet when I suggested this idea to the NAACP’s general counsel—that the nation’s oldest civil rights organization seek to eliminate affirmative action set-asides for minority-owned business—she rejected the notion out of hand. “We don’t want to dilute what the African-American advertising firms have created,” she said. When I floated the same idea to Cyrus Mehri, one of the most established and respected employment discrimination lawyers in the country, he, too, insisted that the fight to integrate the white agencies shouldn’t take business away from black-owned agencies.

But it does. The integration of white institutions poses an existential threat to the viability of historically black institutions. Jackie Robinson didn’t just integrate the Major Leagues; he destroyed the Negro League. Here on Madison Avenue was a textbook example of the left’s third major blunder in dealing with race: ignoring the most fundamental question of post-Jim Crow society. Does black America want in or would it rather stay out?

II.

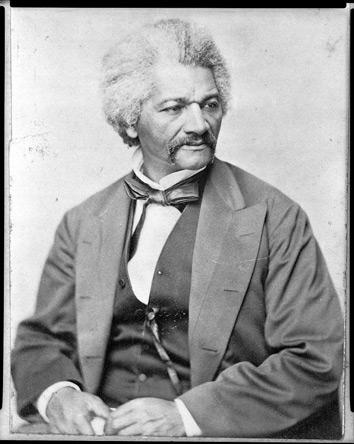

Photo courtesy Library of Congress

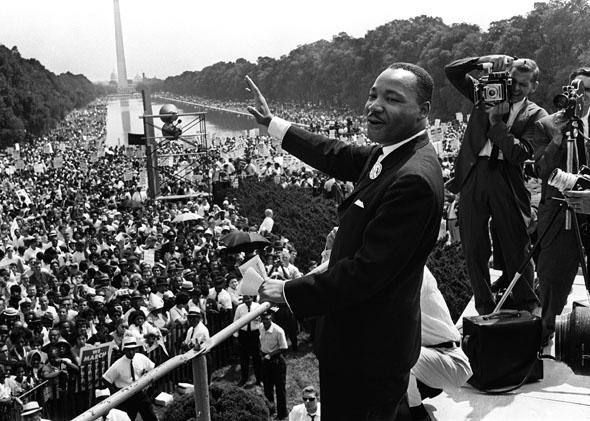

Every year, during Black History Month, and on notable civil-rights-era anniversaries, we convene to debate, yet again, whether or not we’ve finally achieved Dr. Martin Luther King’s “dream” for America. It’s a fruitless exercise, for a variety of reasons, not least of them being the fact that King wasn’t the only civil rights leader with a dream. If we forget to take that into account, if we ignore the complex undercurrents that ran beneath the surface of the civil-rights movement, we can’t begin to understand the ways in which it fell short.

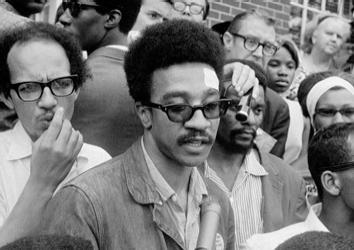

From its earliest moments, the black freedom struggle in America was rife with contradictions and competing factions. The abolitionist movement was split between the aims of Frederick Douglass, who lobbied for the Americanization of the freed slaves, and Martin Delany, the first major proponent of black nationalism. The response to Jim Crow was equally divided, as the black and white activists who joined forces to form the NAACP clashed with Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association and its calls for a return to Africa. Similarly, King’s crusade for integration faced outspoken black opposition as well, and not just from militant radicals like H. Rap Brown.

Photo by Francis Miller/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

In The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, Harold Cruse wrote the definitive account of black America’s inability to confront its internal divisions. The civil rights crusade, he wrote, was in fact an “expedient and makeshift assortment of pilgrimages, haphazardly aligned into a broad movement.” The shared goal of these factions was “freedom” but freedom “to do what?” To join the white establishment? To tear it down? There was no answer. And that, in addition, of course, to the virulence of white opposition, waylaid black America’s journey to the Promised Land—nobody agreed on where the Promised Land actually was. “One cannot have a movement in America,” Cruse said, “rooted in the protest tradition, but also rife with integrationism, separatism, interracialism, nationalism, Marxist and anti-Marxist radicalism, Communist and anti-Communist radicalism, liberalism, anarchism, nihilism, and religionism—and expect such a movement not to be a failure.”

By the time King was assassinated in Memphis, the civil rights movement had reached a critical crossroads: Integrate or separate? Fight to get in or resolve to stay out? On this question, there is a fantastic issue of Ebony magazine that ought to be required reading for every American. It was published in August 1970, and the headline on its cover reads: “Which Way, Black America? Separation? Integration? Liberation?” The whole issue, front to back, is filled with essays and reportage on black America’s splintering coalition. Read as a whole, it’s a fascinating back and forth between mainline integrationists from the Urban League and the NAACP, on the one hand, calling for the complete dismantling of Jim Crow and the shuttering of black institutions to facilitate a migration into the larger society, and militant black nationalists on the other, demanding total separation from white American oppression, an embrace of Afrocentric art and philosophy, community control over black institutions, and the financial reparations necessary to make that possible. Back and forth, they argue, page after page, resolving nothing but giving a crystal clear picture of the problem at hand.

The best piece in the issue is by Ebony’s executive editor, Lerone Bennett, Jr., who points out that these diametrically opposed ideologies did not just belong to warring political factions. Rather, they existed within every black individual. Few blacks were militant radicals in the H. Rap Brown mold, and fewer still were so ardent in their desire for integration that they were excited to leave their traditional communities behind. Bennett writes:

It is a very common occurrence to hear the same crowd applauding integration and separation. Somehow, the complexity of this mood has been overlooked. … Most blacks are integrationists and separationists and pluralists—all at the same time. They are “integrationists” on Monday morning, when they go downtown to meet “the man,” “separationists” when they return to the black community on Monday night, “integrationists” when they go downtown to the movie, “separationists” on Saturday night when they go to an all-black bar or congregate in the playrooms of the gilded ghetto, “pluralists” when they go to the African Methodist or the Pearly Grove Baptist, and “integrationists” on Monday morning when they sigh and go out to meet “the man” again.

The complexity of the issue, Bennett argued, along with the actual needs and wants of black individuals, was being lost in the polarizing debate. The paradox of black America’s predicament was that, yes, in order to gain access to the wealth and resources of society, integration was a necessary step. But without black institutions and group solidarity to provide support, the black community’s ability to sustain itself in a hostile environment would be destroyed. “[T]he essence of our situation at the moment,” he concluded, in what may be the most succinct evaluation of black America’s predicament at the end of the civil rights era, “is that we can neither integrate nor separate. We are caught just now in an impossible historical situation.”

Photo by Bill Peters/Denver Post/Getty Images

III.

In one of history’s great ironies, the grand-scale integrationist schemes embraced by liberals during the civil rights movement took hold only after the rise of Black Pride and ethnic solidarity was well underway. Convulsed by spasms of white guilt, terrified by the prospect of more urban riots, and not really understanding the complex wants and desires of black America to begin with, the white establishment started doing its best to split the difference—give the old-school integrationists the access they demanded, and give the nationalists a nod to Black Power at the same time. Whatever it took to make the problem go away.

So steps taken to dismantle the color line were accompanied by efforts to shore-up the foundations of a separate black America and preserve its cultural norms. Du Bois’ Talented Tenth streamed onto elite white college campuses only to demand, and be given, their own black dorms and student centers. While fair-housing advocates fought to end redlining and move black families into middle-class white neighborhoods, black nationalists denounced integration as a “dispersal” of the traditional black power base; they advocated for local control of black neighborhoods through community development groups bankrolled by liberal philanthropists like the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations. When civil rights groups fought to build scattered-site public housing in order to break up low-income residential areas, the newly formed Congressional Black Caucus fought to keep public housing clustered in black neighborhoods in order to protect their voting districts.

Perhaps the clearest example of the paradox of post-Jim Crow America would come in the world of higher education. When time came for the courts to impose integration on southern school systems, in the case of Adams v. Richardson, the fate of historically black colleges, public ones at least, seemed to be a foregone conclusion. But HBCU advocates stepped in, vigorously petitioning the court to protect their alma maters; since black colleges had done nothing wrong, it was argued, those schools should not be punished for the constitutional violations committed by white schools. Thus did a federal judge turn an impossible historical situation into a legal mandate: per the precedent set forth in Adams, every southern state would be required to create a “unitary system free of the vestiges of state imposed racial segregation.” And they had to do it without closing any black schools. Mississippi, Maryland, Louisiana, et al., have all been trying to square that circle for years. Affirmative action was, in effect, a mandate for white schools to siphon the human and intellectual capital out of black schools—the Jackie Robinson effect. Yet even as their resources were being drained away, HBCUs were now ordered to stay the same size and to support the same infrastructure rather than evolving to face a new reality. The legal precedent that tried to protect black colleges essentially condemned those institutions to decay from within.

One reason integrationists and black nationalists were engaged in such a fiery debate is because both sides knew how fundamentally irreconcilable their two philosophies were. To old-school integrationists, the community development efforts of black nationalists were nothing more than “gilding the ghetto.” Given the realities of global corporate capitalism, set-asides for minority-owned businesses were a romantic delusion, “dangerous nonsense.” All-black dorms and student unions served only to satisfy whites who were more than happy to see blacks “go off in the corner by themselves.” On the flip side, nationalists attacked the work of integrationists as selling out the one thing black America had always relied on most: its solidarity. Open housing efforts would disperse their power base, leaving individuals vulnerable and exposed. Assimilation was “cultural genocide.”

Photo courtesy Warren K. Leffler/Library of Congress

Given black America’s history of being burned by the bad-faith promises of the white establishment—Reconstruction, the Freedman’s Bureau, the 14th Amendment, the 15th Amendment—black leaders had every reason to approach integration with extreme skepticism. And Lerone Bennett was entirely right that neither integration nor nationalism fully satisfied the different needs and moods of the black community. Both were far from ideal. He was also right that the two competing ideologies rested within the soul of each individual—that it was perfectly natural, after a long day fighting to integrate a hostile white workplace, to seek respite in the comfort of the black community after hours. When standing at the crossroads of integration and separation, ambivalence is to be expected. But that’s on a personal level. When ambivalence dictates our approach to governing, it becomes problematic. Economic incentives can only pull in so many directions at once. At a certain point, on a policy level, you have to pick a horse and ride it. If you don’t, your lack of conviction will just leave you going around in circles.

IV.

Exhibit A would be the aforementioned state of race on Madison Avenue. The current iteration of advertising’s racial crisis dates back to an account I worked on just out of college. In 1998, as part of his effort to look tough on crime and win the war on drugs, President Clinton had his Office of National Drug Control Policy, headed by Drug Czar Barry McCaffrey, launch a five-year, $1 billion ad campaign to make lots of those anti-drug commercials that don’t actually get kids off drugs. Ogilvy & Mather, where I worked as a copywriter, was awarded the account—a federal contract that came with all sorts of government oversight, including affirmative action compliance.

Photo by Tim Sloan/AFP/Getty Images

Just a few months into the project, McCaffrey was summoned before the Congressional Black Caucus, at a hearing chaired by Rep. Carolyn Kilpatrick (D-Mich.), to explain the ONDCP’s choice of ad agency. For an account tasked with delivering anti-drug messaging to urban youth, Ogilvy had an alarming “lack of diversity” (it’s true; I was there) and, the CBC said, hearings needed to be held to assess the agency’s minority hiring and retention policies. At the same time, they said, Ogilvy wasn’t doing nearly enough to bring on minority-owned contractors, who, under federal law, were entitled to their cut of the $1 billion anti-drug pie.

For its lack of internal diversity, Ogilvy, along with nearly every other major ad agency in Manhattan, soon found itself being dragged before the New York City Commission on Human Rights, chaired by City Councilman Larry Seabrook, who for the next few years made great sport out of hauling white executives into his chambers to give a bunch of shambling excuses about the dismal history of race and advertising. Eventually, under threat of government sanction and public embarrassment, most of the major agencies agreed to ramp up their minority hiring and retention practices. Seabrook announced Madison Avenue’s single biggest initiative—a $2.5 million diversity commitment from industry giant Omnicom—at a Congressional Black Caucus event on advertising hosted by Kilpatrick. Meanwhile, in October 2000, to bolster the support of minority-owned ad agencies Bill Clinton, flanked by a smiling Kilpatrick, signed an executive order directing federal procurement agencies to take aggressive affirmative action to include minority-owned businesses in government ad buys in order to make advertising “fully reflective of the nation’s diversity.”

Two forms of affirmative action, each pulling in a different direction. Needless to say: Nothing in the industry changed. The conglomerates that control most of the industry scrambled, made token concessions to black agencies, token concessions to improve internal hiring, and spread just enough money around to keep everyone happy, launching multicultural awards shows and minority internship programs all while hoping that the flaws in this non-solution would be overlooked in light of their rekindled “commitment to diversity.”

Of course, some new black hires did make their way into white agencies through the newly refurbished affirmative action pipeline. But at the same time, successful black talent kept going back out the revolving door to work at minority-owned agencies—agencies whose viability was and is sustained by affirmative action contracting laws like Clinton’s. Meanwhile, the lily-white old boys network that controls Madison Avenue wasn’t challenged in the slightest and the industry’s racial problems weren’t any closer to being solved. Then, in 2008, along came Cyrus Mehri and the NAACP to insist that Madison Avenue repeat the same exercise all over again. The only people who get hurt in this cycle are the ambitious and talented black people who could use a coherent policy to help them get ahead in advertising.

The thing about set-asides for black-owned agencies is that they seemed like a fine idea at the time, back in the 1970s. The law came along and mandated that white agencies had to give black agencies, let’s say, 10 percent of the Pepsi account. Back then, 10 percent of the Pepsi account was a huge boon to black entrepreneurs, millions of dollars in business. Today, many younger black executives in the industry are understandably tired of working this way. They don’t want 10 percent of the Pepsi account—they want the Pepsi account. They don’t want to work on one side of the cultural divide. They want to close that divide. Steve Stoute, a former music industry exec and co-owner (along with Jay Z) of Translation, a “transcultural advertising agency,” is one of these individuals. But he and black entrepreneurs like him have had to struggle against the bias and institutional balkanization that minority set-asides have created. They’re trying to build a 21st-century media enterprise and they’re stuck dealing with a business model built in the 1970s.

When my book on the legacy of Jim Crow came out, I did an interview on the subject of black agencies with AdAge. Stoute read it and called me to ask if I would join him for a panel discussion at the upcoming industry conference, Advertising Week. He wanted to have a blunt conversation about how minority set-asides have stunted the industry, how they’ve actually limited black entrepreneurs. “Great,” I said. There was only one problem: No one wanted to have that conversation with us. No one. Conference sponsors and white execs who were supposed to be on the panel all backed out. The event was canceled and Stoute had to host a panel discussion about the power of diversity. Naomi Campbell showed up to talk about her new reality show.

Photo by Steven Schaefer/AFP/Getty Images

High-ranking execs in general market advertising—at least the ones I’ve spoken with—are fully aware that maintaining the politically protected status of minority agencies is wholly incompatible with the integration of the industry at large. But no one wants to address it head on. Because why would they? It is verboten for an industry executive to do anything but cheerlead for more diversity at white agencies. To take the ideologically consistent position on phasing out set-asides for minority businesses would be to invite accusations of racism from the segment of the black community that supports them, to risk another round of hearings. Why bother with that when you can just throw enough money at the problem to make it go away? Whenever this impossible historical situation rears its head, the easiest thing for people to do is just take both sides, which is the same as not taking any side at all.

V.

The last and greatest question of the civil rights movement—Which Way, Black America?—remains unanswered. You see it in the tension between declining enrollment at HBCUs and calls to reinvigorate affirmative action at majority-white schools. You see it in the conflict between maintaining majority-black voting districts and the drive to groom more black politicians electable for statewide office. You see it everywhere.

“[T]he world of black Americans is full of divisions,” said Bayard Rustin, organizer of the 1963 March on Washington. “Only the most supine of optimists would dream of building a political movement without reference to them.” And yet here we are, with a political movement that’s done exactly that. Ever since Barack Obama beat John McCain, much ink has been spilled over the fact that, in a country trending toward “minority majority” status by 2042, the lily-white GOP has painted itself into a demographic corner. Far less attention has been paid to fact that the Democrats have built their house on an ideological fault line. The current Democratic majority can only win by continuing to run up huge margins in both the black and the Hispanic vote, yet there are vast differences in what the members of those communities want and desire, goals that are often in direct conflict with one another. To take an ideologically consistent position on the issue of integration would be to risk losing the support of some percentage of black voters. Which is why you never see Democrats doing it, at least not in front of a microphone during an election year. Just like the nervous white executives at Advertising Week, they’d rather cancel the talk and host a panel discussion about diversity.

And it is the prevalence of that word, diversity, that reveals the lack of conviction among liberals on how to deal with the color line. Madison Avenue has an alarming “lack of diversity.” Network television needs “more diversity.” People rarely call for “integration” anymore. Integration is a word that constitutes an existential threat to historically black institutions; terms like black nationalism and separatism connote something too extreme—we stopped using those a long time ago. But diversity … the genius of diversity is that it can mean whatever you want it to mean. You can call for the integration of white ad agencies, and that is promoting diversity. Then you can go give a multicultural achievement award to the CEO of a black ad agency, and that is also promoting diversity. You can demand more affirmative action at white colleges, and that makes you a champion of diversity. And when you decry the dwindling enrollment at HBCUs, you are a champion of diversity yet again. To boast about your commitment to diversity is simply to say, “I agree with whichever group of people I happen to be standing in front of at the moment.”

By championing all this diversity we’ve pandered to both sides while offering concrete and ideologically coherent solutions to neither. Black America today is neither in nor out. The children of the civil rights revolution do not enjoy the full power and privileges of membership in the establishment, nor do they enjoy the same group solidarity and identity that sustained them through their crucible of oppression. One might consider this the worst of all possible outcomes.

Martin Luther King certainly did, when he wrote his essay “The Ethical Demands of Integration.” “We do not have to look very far,” King wrote, “to see the pernicious effects of a desegregated society that is not integrated. It leads to ‘physical proximity without spiritual affinity.’ It gives us a society where men are physically desegregated and spiritually segregated, where elbows are together and hearts are apart. … I may do well in a desegregated society, but I can never know what my total capacity is until I live in an integrated society. I cannot be free until I have had the opportunity to fulfill my total capacity untrammeled by any artificial hindrance or barrier.”

Fifty years later, we still have a society that is desegregated but not integrated. The principal blame for this lies, yes, of course, with the massive white resistance to integration, but that fact shouldn’t stop us from criticizing the ways in which racial justice advocates have failed to adequately challenge that resistance, and one of the single biggest failures has been the inability and unwillingness to resolve the conflicts that sundered the civil rights movement in the first place.

Photo by AFP/Getty Images

If we ever want to seriously grapple with the problem of the color line, step one would be to start using language that’s intellectually honest. We can’t have a real debate about “diversity” because the word doesn’t actually mean anything. Let’s strike it from our collective vocabulary. Integration and assimilation are perfectly good words. They describe actual things. Black nationalism and racial solidarity are also great words. They have actual meanings, too. When you use actual words with actual meanings, you can have a healthy and productive debate about which ideas you actually believe in.

If we take seriously the argument that society should take aggressive steps to remedy the underrepresentation of blacks at majority-white institutions, we should be candid about the hard choices those actions will require. In a world of limited resources, robust efforts to integrate corporate America and higher education and the halls of the U.S. Senate will bring about greater social and cultural assimilation and necessarily come at the expense of historically black businesses, colleges, and voting blocs. No one’s interests are served when we try to pretend otherwise.

Having spent the past few years reporting on the color line, from the corporate boardrooms of Madison Avenue to the suburbs of Birmingham, Ala., I’ve seen up close the reality of how this plays out. When fighting against a white-supremacist power structure, the allure of Black Power and ethnic solidarity is undeniable. But things like minority set-asides for black ad agencies don’t actually make for a stronger black America. In reality, they’ve served as a form of state-incentivized segregation. Policies that draw blacks away from the centers of power—even if those policies are dressed up in the trappings of “diversity” and minority-empowerment—should be discouraged. On this front, the logic of integration is, to my mind, pretty airtight. It is the only way to access the places where real wealth resides and true power is exercised, and to ensure that wealth and power are not being wielded against you.

This is not to say, as so many white people often dismissively do, that it’s time for blacks to assimilate and get over it, that historically black colleges are categorically irrelevant, and so on. Navigating the push and pull of integration and ethnic nationalism requires patience and understanding. That’s true even with something that may seem comparatively minor, like the fate of a few black ad agencies. Advertising provides the financial foundation for practically our entire news and entertainment landscape. The fact that there are white sitcoms and black sitcoms, that there are white news sources and black news sources all of that is related to the fact that we’ve built a system where “white” advertising goes over here and “black” advertising goes over there. Those media outlets and organizations, the very channels through which we conduct our national conversation about race, could face drastic change just from striking down a few minority-contracting laws—and some might not survive the transition.

I for one think it’s time to make that change. But I also realize that you can’t alter the existing system constructively without first winning the support of the people who rely on it for their weekly paychecks, their career prospects, and their sense of identity. People have to see integration as an overall win, even if it comes with a short-term loss. If we ask black America to give up 10 percent of the Pepsi account without offering a reasonable hope that it can win 100 percent of the Pepsi account, then black America will never surrender its 10 percent of the Pepsi account.

Perhaps the solution lies in recognizing, as Lerone Bennett did, that the aims of Black Power and integration are not so incompatible as we sometimes imagine. “Too many people think blackness means withdrawing and tightening the circle,” Bennett wrote. “On the contrary, blackness means expanding and widening the circle, absorbing and integrating rather than being absorbed and integrated.” That sounds about right to me. Reasonable people can disagree, of course, and well we should. Ideological differences should be aired and debated and, ultimately, voted on. At present, Republicans don’t have much to contribute to his conversation. The commitment to acknowledge past mistakes, purge outdated orthodoxies, and establish a clear moral vision must come from the left, or it won’t come at all. And it starts with answering one fundamental question: Which way?