I.

In 2009, I attended the NAACP’s 100th annual convention at the Midtown Hilton in New York. Not just the centenary celebration for the nation’s oldest civil rights organization, this was also the group’s first convention under our newly inaugurated black president. The theme of the week’s events was to pay homage to the great civil rights victories of the past while at the same time defining a new mission for the next century. But on the night NAACP President Benjamin Todd Jealous took the stage for his big speech, when the subject turned to affirmative action, he didn’t sound like he was charting a new course so much as doubling down on the orthodoxy of the past. “The only question about affirmative action,” Jealous declared, “isn’t whether or not we need the hammer. The only question is whether or not the hammer is big enough!”

The line was met with thunderous applause. At the time, this didn’t really stand out to me, because, like a lot of well-intentioned but minimally informed white liberals, I believed in affirmative action. I didn’t have terribly strong convictions about it, but given America’s history it generally seemed like “the right thing to do.” That was five years ago. Then, in the course of writing a book about the history of the color line and our efforts to erase it, I took a closer look at the origins of affirmative action, and its results. Having done so, I’m a believer no more.

In part because of recent Supreme Court cases like Fisher v. Texas, the current national conversation about affirmative action has focused mostly on its use in college admissions, but my focus here will be on affirmative action in the white-collar workplace, the failure of which I observed up close during my years in the advertising industry. Race-conscious policies in college admissions and corporate hiring are different creatures, with different pros and cons, but I came to see that they also share some common, troubling flaws.

When I think back now to the rousing applause affirmative action earned at that Hilton ballroom, I can’t help but wonder why, 45 years down the line, liberals like Jealous are still so fervently devoted to a program so plainly inadequate and ill-conceived from the start. Having botched the effort to integrate American schools through the overzealous misuse of an otherwise valuable instrument, the school bus, the left’s second great blunder on race was pinning the economic fortunes of black America on affirmative action.

II.

Proponents of affirmative action tend to glorify the program by lumping it in with the great liberal victories of the civil rights movement. The phrase “affirmative action” first appeared in President Kennedy’s Executive Order 10925, which called for “affirmative action” to be taken to ensure people were employed “without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin.” And Lyndon Johnson is usually given credit for enunciating the principles of affirmative action when he called for reparative economic justice for black America in his famous “To Fulfill These Rights” speech at Howard University, saying, “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and say, ‘You are now free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair.”

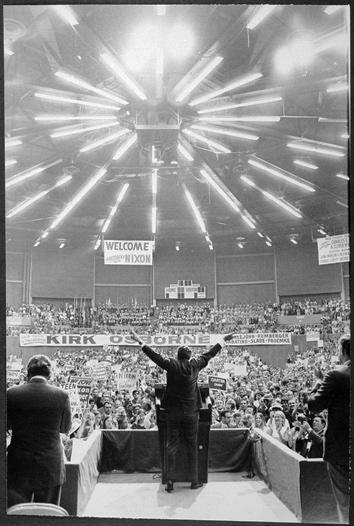

But neither Kennedy nor Johnson ever implemented anything resembling what we now describe as affirmative action—i.e., quotas and set-asides—on the economic front, largely because the Democratic party was beholden to Big Labor, whose unions were adamantly opposed to quotas of any kind. So while the great liberal crusade of the 1960s produced victories in the area of civil rights, it did little in the way of producing actual jobs for black Americans; in some states, black unemployment under Kennedy and Johnson actually went up, hence the frustration that exploded in the urban riots of Watts, Newark, and elsewhere. When Vietnam forced Johnson out of office, the task of implementing a program of reparative economic justice for the victims of slavery and segregation fell to our 37th president, Richard Milhous Nixon.

That Richard Nixon was racist is well beyond dispute—he believed that, moral objections to abortion aside, the practice was justified in the case of mixed-race pregnancies. When giving instructions to the aide who scheduled his appointments and photo ops, Nixon said the Oval Office calendar should have “just enough blacks to show that we care”—setting a precedent for Republican racial engagement that stands to this day. But Nixon wasn’t just racist in the sense of thinking blacks inferior; he was racist in the sense that he subscribed to an actual taxonomy and hierarchy of race—the idea that different groups possess inherent qualities. Asians are smart and industrious. Jews are crafty but lack moral fiber, and so on. When the first wave of studies were published purporting to show that blacks have lower IQs than whites, Nixon, in a conversation with domestic aide Daniel Patrick Moynihan, said he “couldn’t agree more” with the findings. The president was quite generous on the subject of what black people were good at: “Athletics isn’t a bad achievement. You look at the World Series. What would Pittsburgh be without a hell of a lot of blacks?” But he was far less charitable when it came to black talent in other areas: “… when you get to some of the more shall we say profound, rigid disciplines, basically, they have a hell of a time makin’ it. … In terms of good lawyers, even though a lot of them go to law schools, I mean, it is not really their dish of tea.”

Marion S. Trikosko/U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection/Library of Congress

Racist as he may have been, Nixon was also a pragmatist. With America’s cities beset by riots, he knew he had to take steps “not to have the goddamn country blow up.” Blacks needed jobs. And as someone who had grown up poor, Nixon did believe in the basic principle of what he called a man’s “right to earn.” Everyone, black or white, had a right to earn a decent living for his family. Nixon just had a limited opinion of what blacks were capable of earning. Another thing the president told Moynihan was that it was his job as president to be aware of the fact that blacks have “basic weaknesses,” and that those weaknesses needed to be taken into account when it came to formulating policy.

The way in which affirmative action was implemented speaks volumes about the motivations behind it. Nixon’s first task upon taking office was to resolve the impasse between civil rights leaders and skilled labor unions. In his first address to Congress, the president announced what became known as the Philadelphia Plan, which imposed goals and timetables for race-based hiring in the city’s unions. Prior to the Philadelphia Plan, under Kennedy and Johnson, affirmative action had always meant to take affirmative action to ensure discrimination was not taking place. Now, affirmative action meant imposing racial preferences and quotas. After its launch in Philadelphia, the program was rolled out in dozens of other cities nationwide. In the meantime, the White House was busy stuffing racial-preference policies into the federal bureaucracy wherever it could find room. In the spring of 1969, Nixon expanded affirmative action mandates from government procurement contracts and applied them to any institution that received any federal funds of any kind, which brought universities, research institutions—basically everyone—into the fold. Then Nixon issued Executive Order 11478, which called for affirmative action in all government employment, bringing huge numbers of black workers onto the federal payroll. Racial preferences, as we know them today, were now sewn into the fabric of the country.

Photo courtesy Jack E. Kightlinger/White House Photo Office/National Archives and Records Service

And affirmative action “worked.” The most immediate and measurable impact was in government hiring. Blacks had always enjoyed relatively better employment prospects in the public sector, and affirmative action greatly enhanced that. By the early 1970s, 57 percent of black male college graduates and 72 percent of black female college graduates were employed in government positions. The private sector also went on a hiring binge. Impelled by the fear of more urban riots, the Fortune 500 launched a flotilla of affirmative action programs aimed at getting as many black hires in the door as quickly as possible. After decades of economic stagnation, between 1969 and 1972, total black income rose from $38.7 billion to $51.1 billion, a 32 percent jump in just three years.

Richard Nixon put more money in black wallets than JFK, LBJ, and MLK combined. While they never embraced Nixon, black Americans and their white liberal champions fell in love with quotas and set-asides. Many of the moderate and liberal Republicans in the White House had faith in affirmative action, too. Nixon’s Secretary of Labor George Shultz, upon his nomination, acknowledged that black unemployment was the most pressing labor issue in the country, and believed that the Philadelphia Plan would offer a useful model for cities across the country. Even some conservatives were on board. Prominent Nixon-supporter William F. Buckley called for “a pro-Negro discrimination” in order to address the problem of unemployment.

The president, however, felt differently. Just weeks after calling the Philadelphia Plan “historic and critical” in Congress, Nixon jotted a note to domestic aide John Erlichman calling it “an almost hopeless holding action at best,” saying “let’s limit our public action and $—to the least we can get away with.” Nixon’s primary concern in the Oval Office was to make his mark as a great foreign policy leader. Vietnam, China, the Soviet Union—these were his main preoccupations. He wanted the home front happy and humming along so that he’d be free to spend his political capital overseas, and his approach to the volatile issues of race reflected this. Staunch opposition to school busing and fair housing would appease suburban white voters. Affirmative action on the jobs front would appease middle-class black voters, end the riots threatening corporate America’s bottom line, and generally keep the racial question tamped down long enough for Nixon to win re-election in ’72.

Given the immediate positive impact that affirmative action had, it was perfectly reasonable for liberals to want to believe that it could be, at long last, an answer to economic discrimination and structural inequality. But it wasn’t. Not remotely. For starters, the quotas and mandates put in place were almost comically easy to evade. The skilled labor unions required to admit blacks engaged in practices known as checkerboarding (putting all the black hires on government-contracted job sites while ignoring the quotas everywhere else) and motorcycling (shuffling black hires from job site to job site depending on where federal inspectors were slated to show up). Quotas may have seemed like a positive development, and they did produce some jobs, but they also turned black employment into a numbers game—and gave employers a way to game the numbers.

Affirmative action in state, local, and federal government offered decent jobs with decent wages, but the side effect of all this government hiring was to relieve the white collar private sector from having to truly confront the issue in its own staffing. For the minimal hiring it did do, corporate America made sure to meet its new quotas in the least disruptive way possible, hiring blacks for back-office roles in the accounting department, for example, or creating make-work departments that had no power and did nothing, like the community outreach or “social responsibility” department. Again, these were decent jobs with decent wages, but they diverted blacks from the business units where real decisions were made. Affirmative action offered the illusion of reparative justice wrapped up in the rhetoric of empowerment, but its net result was to absorb and neutralize black demands for equality, not fulfill them.

Photo courtesy Oliver F. Atkins/National Archives and Records Administration

Another effect of affirmative action was that it created a short-term labor shortage in the black middle class, because that’s who affirmative action was designed to help. In Nixon’s taxonomy of race, there was a clear division between “the good blacks” and the rest of urban America. “There are 35 percent of blacks we can do good with,” he told his staff. And it was squarely at this group that he aimed his policies. If you look at the areas where affirmative action was implemented—college admissions, corporate hiring, minority business loans, skilled labor unions, government office jobs—you’ll notice that most of them aren’t really things that will help you if you’ve never graduated from high school.

The urban poor were hopeless, just “little black bastards on the welfare rolls at $2,400 a family,” Nixon said, and for this group his policy aims were clear. Meeting notes taken by Nixon’s Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman detail the president’s directives:

Shift of policy of helping and backing the strong—instead of putting all effort into raising the weak

build incentives for the strong + positive

give the fellowships to them instead

don’t aim manpower programs at unemployed black male teenager …

For the unemployed black male teenager, Nixon had a very different social program to offer. During his 1968 campaign, against the backdrop of violent riots in America’s inner cities, the candidate made repeated and thinly veiled calls for “law and order,” criminalizing the urban poor in the nation’s mind and promising his silent majority that lawbreakers would be dealt with harshly under his administration. Once in office, Nixon launched his now infamous “War on Drugs,” planting the seeds that have grown, decades later, into a system of mass incarceration—something all-too-familiar to the unemployed black male teenager of today. As the 1970s progressed, the black underclass was increasingly left behind while the black middle class was movin’ on up—not to the East Side, typically, but to majority black suburbs where they continued to be isolated from the schools and social networks that offered access to greater economic opportunity.

Did millions of people do well under affirmative action? Yes. A bribe only works if you actually give somebody something. But the benefits that accrued to black America under affirmative action could almost be considered a byproduct of the program’s actual endgame: to give black people just enough to stop rioting and leave the white establishment to go about its business. While some black people used quotas and set-asides as a foothold to climb into genuine positions of power, the effect of affirmative action overall was to funnel upwardly mobile blacks into a separate employment pipeline where their aspirations were held in check, where they exercised very little authority, and where their progress depended on government intervention. Thanks to affirmative action, the black middle class was now vested in the very system the civil rights revolution had sought to overthrow.

III.

When affirmative action was first implemented, it was not met with a broad backlash from white America. Like Nixon, the average white voter was inclined to do something “not to have the goddamn country blow up.” Then the 1970s recession hit and access to jobs felt more like a zero-sum game. It was then that white people began to use phrases like “reverse racism” and “haven’t we done enough for them already?” The parties flip-flopped. Liberals, who had once disdained racial quotas as being antithetical to true liberty and justice, embraced them for the short-term leverage they provided. Republicans, once in favor of set asides and preferences as a cheap and easy solution for appeasing blacks, now saw them as a wedge issue useful for stirring up disaffected whites. Then Ronald Reagan was elected president and started undermining racial preferences just as quickly as Richard Nixon had put them in place.

Photo courtesy White House Photographic Office/National Archives and Records Administration

To this day, Reagan is vilified by the left as the man who crushed America’s dream of racial equality by rolling back affirmative action. But of course Reagan started rolling back affirmative action. Why wouldn’t he? Affirmative action was created by the Republican establishment to protect the Republican establishment. Once that group felt protected, once it was Morning in America and the riots had been reduced to occasional flare-ups in Liberty City and Crown Heights, affirmative action had largely fulfilled its purpose: Blacks had been pacified enough that their needs could be safely ignored. So why not start winding it down?

The problem with winding it down was that black Americans were now invested in it, had banked their hopes on it. By embracing affirmative action as a solution to economic disparity, the liberal establishment encouraged black Americans to double down on something that was never intended to close the economic gap in the first place. As a result, they were promised something that the government can’t actually deliver.

For starters, the government doesn’t actually enforce affirmative action. The Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs is technically responsible for ensuring that America’s affirmative action policies are carried out. Every year, every company with at least 50 employees doing at least $50,000 worth of business with the government has to file an Affirmative Action Plan with the OFCCP. This report tracks every interaction that takes place between that company and minority job candidates: new hires, promotions, demotions, department transfers, etc. All of this information is diligently, exhaustively compiled. Then nobody reads it. To police affirmative action in the largest economy in the world, the OFCCP has about 600 staffers. In a good year they review around 4 percent of these AAP filings. Of that, they investigate less than 1 percent.

But even if the government were keeping better tabs on affirmative action, the bigger problem is that its jurisdiction doesn’t reach the parts of the economy where affirmative action is most desperately needed: the places where real money is made and real power is allocated. The best example of this is the industry that dominates so much of our economy today: the technology sector. Silicon Valley’s racial diversity is pretty terrible, the kind of gross imbalance that inspires special reports on CNN.

It’s a dismal state of affairs, but how could it really be otherwise? Silicon Valley isn’t just an industry; it’s a social and cultural ecosystem that grew out of a very specific social and cultural setting: mostly West Coast, upper-middle-class white guys who liked to tinker with motherboards and microchips. If you were around that culture, you became a part of it. If you weren’t, you didn’t. And because of the social segregation that pervades our society, very few black people were around to be a part of it.

Some would purport to remedy this by fixing the tech industry job pipeline: more STEM graduates, more minority internships and boot camps, etc. And that will get you changes here and there, at the margins, but it doesn’t get at the real problem. The big success stories of the Internet age—Instagram, YouTube, Twitter—all came about in similar ways: A couple of people had an idea, they got together with some of their friends, built something, called some other friends who knew some other friends who had access to friends with serious money, and then the thing took off and now we’re all using it and they’re all millionaires. The process is organic, somewhat accidental, and it moves really, really fast. And by the time those companies are big enough to worry about their “diversity,” the ground-floor opportunities have already been spoken for.

A place like Silicon Valley doesn’t have an established pipeline where the government can mandate there be X number of minority applicants per year who can then be tracked up the corporate ladder each fiscal quarter. A system has to have rules in order for authorities to make sure that those rules are being applied fairly to people of color. The legal profession is very mature. It has lots of rules. Municipal labor unions have rules. Silicon Valley doesn’t have any rules. Hollywood doesn’t have any rules. Media and publishing used to have rules, sort of, but Silicon Valley is destroying those rules as we speak and doesn’t seem to be replacing them with any new ones.

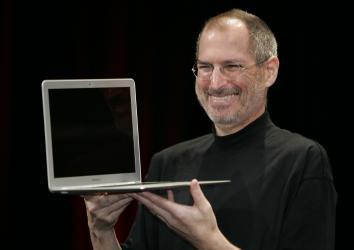

Affirmative action treats workplace discrimination like a bureaucratic, process-based problem. In reality, workplace discrimination stems from a very nebulous social and cultural problem. The government claims it can regulate the racial composition of our professional lives, but too much of what we call “work” is actually rooted in the messy, socially segregated realm of our personal lives. How many affirmative action compliance officers were stationed in Steve Jobs’ garage while he and his buddy Steve Wozniak assembled the first Apple? Zero. It’s possible to track what goes on in the human resources department and in the minutes of corporate board meetings, but too much of the economic life of this country transpires in the spaces in between. Racial preferences can provide just enough jobs and material support to keep up the illusion that we’re moving toward equality, but no program can give black Americans real, sustained access to the places where the prerogatives of wealth and power are exercised. Only social and cultural integration can do that—the kind of integration Nixon opposed while he was advancing affirmative action.

Photo by Tony Avelar/AFP/Getty Images

Of course, at first blush, the case against workplace affirmative action would seem to make the case for collegiate affirmative action: Admit black students to majority white colleges, and maybe a black student ends up in Mark Zuckerberg’s dorm room when he starts Facebook. And to an extent that’s true. Unlike the Hobbesian state of nature that is the 21st-century job market, college admissions are a methodical, bureaucratic process where the special circumstances of minority students can be given extra weight and duly monitored for enforcement. And no matter what apoplectic conservatives say, racial diversity is no more “unfair” a standard than legacy status or geographic distribution or any of the other subjective criteria used in assembling a freshman class.

But does collegiate affirmative action, like its workplace cousin, just come too late in the game? In his memoir Reflections of an Affirmative Action Baby, Yale Law professor Stephen Carter—who describes himself as both a beneficiary and a victim of racial preferences—makes a sound argument. Because of the thorny politics and stigmas that inevitably come with race-conscious remedies, those remedies should start aggressively at a very young age and then, for everyone’s good, taper off over time. If a 5-year-old from a disadvantaged background is given a leg-up to get into a good elementary school, that is not likely to be a stigma he will carry around as an adult—and you really have to try hard to begrudge helping out a 5-year-old. By contrast, for the thirtysomething black professional forced to walk in the door with whispers of “diversity hire” trailing her down the hallway, affirmative action can be a real problem. It serves as a diminishment of her talent and hard work. As much as affirmative action might help her get a foot in the door, it becomes a burden she has to carry from that day forward.

Starting young would also likely increase the effectiveness of affirmative action. Thanks to structural inequality in access to resources, the statistical gaps between black and white Americans start the day we’re born, with disparities in birth outcomes and infant mortality rates. Those gaps get wider with each passing year, as privileged kids get greater access to pre-K and extra tutoring until, come college application time, the gaps have become chasms. You’ve got a legion of helicopter-parented white kids, their resumes crammed full with every AP course and extracurricular whatnot under the sun—up against black students from working- and low-income backgrounds whose resumes are more likely to show a lot of unrealized potential, because AP physics and summer language camps in Vermont simply weren’t available to them. We’re asking a hell of a lot of college admissions officers if we expect them to close that gap with nothing more than a weighted point system for processing applications. In the end, most colleges end up cherry-picking the black kids with the best SAT scores in order to show their “commitment to diversity,” while the real problems of inequality go unaddressed. That hardly seems like a solution.

Affirmative action becomes more contentious, more stigmatizing, harder to enforce, and less effective the older its purported beneficiaries are. Which means we’re investing a lot of time and energy at the end of the pipeline that should be invested at the front of the pipeline. You integrate the workplace by integrating the high school cafeteria. Or, better yet, the elementary school playground. Racial preferences in college admissions may be better than racial preferences at the office, but that’s not saying much. Affirmative action remains exactly what Richard Nixon said it was. It’s a holding action, and a pretty hopeless one at that.

IV.

Today, the statistics on black and white inequality are so unchanging that they can be recited by rote: The black unemployment rate holds steady at double the white unemployment rate; the median net worth for black households is about 7 percent of white households; annual per capita income for blacks is 62 cents for every dollar of per capita income for whites.* When presented with these figures, supporters of affirmative action typically use them as evidence that conservatives kept affirmative action from working. Others say the statistics are proof that affirmative action didn’t really work that well to begin with. But there’s always the third option to consider: that persistent racial inequality is, at least in part, the result of affirmative action working exactly as it was intended to.

Photo courtesy Oliver F. Atkins/National Archives and Records Administration

It’s not an accident that affirmative action and Nixon’s “law and order” campaign are both rooted in the same historical moment: the backlash to civil rights. Liberals want to believe that affirmative action is a social good and mass incarceration is an unalloyed evil. The left wants to enshrine the former and abolish the latter. But affirmative action and mass incarceration are just two sides of the same coin: one program to manage the aspirations of the black middle class, one to contain the anger of the black underclass. Both are forms of social control, and neither has anything whatsoever to do with repairing the real damage wrought by slavery and segregation.

If we ever want to start fixing these problems, we can start by being honest about what affirmative action really is. Some advocates are doing just that. In The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander writes candidly about the symbiotic relationship between affirmative action and mass incarceration, saying “perhaps the two are more linked than we realize,” and asking blacks to consider if they’ve been “bought off” by a bribe. The consensus is starting to crack, a little. But to judge from the rhetoric that still surrounds the issue, most progressives are nowhere near ready to admit the truth: that the liberal establishment pinned the economic hopes of the civil rights revolution on a program set up by a president whose racial philosophy was based on the idea that blacks make great athletes and Asians are good at math.

The latest idea, floated by those who’ve started to admit the shortcomings of race-based affirmative action, is to replace it with class-based affirmative action. But that’s an equally unpromising idea. The nature of affirmative action is that it skims. It elevates the best and the brightest of a disadvantaged group while doing nothing to eliminate the root causes of that group’s disadvantage. Just as cherry-picking all the black kids with good SAT scores hasn’t brought about the end of racism, cherry-picking all the poor kids with good SAT scores isn’t going to do much to end poverty.

As big a detour as it’s been, you can’t just get rid of affirmative action. There is a separate and unequal economy that depends on it. Racial preferences may have taken black America into a socioeconomic cul de sac, but you can’t just tear up the road and leave people with no way to get out. Fortunately, the one thing the left does have is the leverage and the political capital to end affirmative action in the right way. Right now, the Democratic party and the racial justice movement are sitting on a junk heap of racial preference programs that aren’t doing anyone much good, and they lack the substantive programs they need: a true, New Deal–style reformation that repairs the infrastructure of our cities, ends mass incarceration, provides access to early education and paid family leave and job training and other programs that put all of black America on more solid footing. Since Republicans seem to want affirmative action gone so badly, if it were me, I’d be out horse trading. Just as the Obama administration is letting Washington and Colorado opt out of federal marijuana prohibition, let state and local governments opt out of affirmative action mandates, but only in exchange for opting in on universal pre-K and other things that working families actually need.

If conservative politicians and judges are allowed to end affirmative action for the wrong reasons—a very real and immediate possibility—it’s safe to say that race relations in our great land will not improve. The onus falls on liberals to end it for the right reasons and to use that opportunity to replace it with something meaningful. Otherwise the status quo is never going to change, and America will keep on wandering in circles well short of the Promised Land.

Next week: How the left failed to answer the most fundamental question of the civil rights era.

Correction, Feb. 11, 2014: This article previously stated that black workers make .62 cents for every dollar white workers make. The correct amount is .62 dollars, or 62 cents. (Return.)