In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the United States suffered through a skyjacking epidemic that has now been largely forgotten. In his new book, The Skies Belong to Us: Love and Terror in the Golden Age of Hijacking, Brendan I. Koerner tells the story of the chaotic age when jets were routinely commandeered by the desperate and disillusioned. In the run-up to his book’s publication on June 18, Koerner has been writing a daily series of skyjacker profiles. Slate is running the final dozen of these “Skyjacker of the Day” entries.

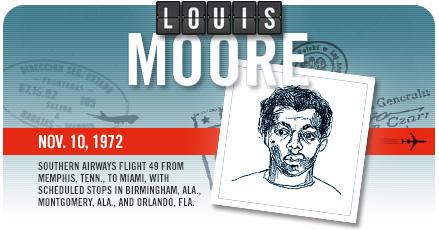

Name: Louis Moore

Date: Nov. 10, 1972

Flight Info: Southern Airways Flight 49 from Memphis, Tenn., to Miami, with scheduled stops in Birmingham, Ala., Montgomery, Ala., and Orlando, Fla.

The Story: The airlines long viewed hijacking as a manageable risk. They believed that if they acquiesced to all of a skyjacker’s demands, a favorable outcome was guaranteed—the passengers would go unharmed, the plane would be returned intact, and any ransom would likely be recovered after an arrest was made. Based on this assumption, the airlines were convinced that it was cheaper to endure periodic skyjackings than to implement invasive security at all of America’s airports. The Southern Airways Flight 49 incident revealed the folly of this mindset.

The hijacking traced back to a dispute between 27-year-old Louis Moore and the city of Detroit. In November 1971 Moore had sued the city for police brutality. Then in October 1972 Moore and one of his friends, Henry Jackson, were arrested for sexual assault—a charge the two men alleged had been trumped up in retaliation for the lawsuit. Moore and Jackson fled the city after posting bail, joined by Moore’s half brother, Melvin Cale, a burglar who had escaped from a Tennessee halfway house. The fugitive trio made a pact to teach Detroit’s authorities an unforgettable lesson.

Armed with guns and hand grenades, which they smuggled aboard the DC-9 in a raincoat, the three men commandeered Flight 49 over central Alabama. Their demands were unprecedented: 10 parachutes, 10 bulletproof vests, and $10 million in cash, along with a White House letter certifying the money as an irrevocable “government grant.”

Flight 49 headed for Detroit, where the hijackers wanted the ransom delivered, but heavy fog forced the plane to land in Cleveland instead. The hijackers, who had consumed much of the plane’s liquor during the northbound journey, next asked to go to Toronto, where Southern Airways offered them $500,000. Moore rejected this sum and ordered the plane to fly to his hometown of Knoxville, Tenn.

“This is going to be the last chance,” he radioed Southern officials as Flight 49 soared over Lake Ontario. “If we don’t get what we want, we’re going to bomb Oak Ridge.” Moore was referring to Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 20 miles west of downtown Knoxville. The facility’s centerpiece was a nuclear reactor powered by highly enriched uranium-235, a primary component of many fission bombs.

As Flight 49 circled over Oak Ridge, Southern scraped together every last nickel it could—$2 million in all. The airline had no choice but to gamble that the hijackers would be so overwhelmed by the sheer heft of the ransom—approximately 150 pounds—that they wouldn’t bother to count it.

Flight 49 landed in Chattanooga, Tenn., to pick up the money. Just as Southern had hoped, Moore, Jackson, and Cale were too awestruck by the abundance of cash to realize they had been duped. The hijackers celebrated their new wealth by handing out wads of cash to passengers and crew members; the captain and co-pilot alone received $300,000.

But the ecstatic hijackers reneged on their promise to release the passengers in Chattanooga. They instead demanded to be flown to Havana, where Cuban authorities refused to let them disembark. The flight then went to an Air Force base near Orlando, where FBI agents severely damaged the DC-9’s landing gear with gunfire. Yet the hobbled plane still managed to take off and head back to Havana. This time, after a harrowing landing, Cuban soldiers arrested the hijackers and impounded their ransom so that it could be returned to Southern. A furious Castro promised one of pilots that the three men would spend the rest of their lives in tiny boxes. (A full map of Flight 49’s bonkers journey can be seen here.)

The Upshot: In direct response to Flight 49’s flirtation with nuclear catastrophe, the physical screening of all airline passengers began on Jan. 5, 1973. Cuba returned Moore, Jackson, and Cale to the U.S. in 1980, much to the hijackers’ relief. “The [U.S.] jails will look like a country club, a paradise,” Cale told reporters. Moore, who served another seven years in the U.S., now lives in Knoxville.