On May 15, 1915, a small convoy of automobiles touched their rear tires to the cool waters of the Atlantic on Coney Island, just long enough for news photographers to snap a few shots. The cars left the beach and puttered up through Brooklyn and into Manhattan, hit Times Square, crossed the Hudson on the Weehawken Ferry, then set about following the sun west toward San Francisco.

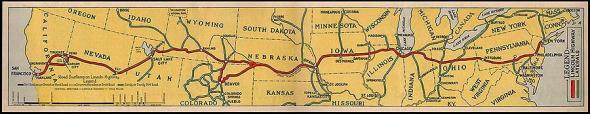

In 1915, the way you traveled from New York to San Francisco, if you were making the journey in one of the nation’s roughly 2 million motorcars, was by plodding across America’s interior on something called the Lincoln Highway. This was not a highway as we think of one today. The Lincoln Highway was a cross-country route made up of existing roads and trails marked with special red, white, and blue signs bearing a large L. It had no grade separations, no special on- or off-ramps to control access, none of the engineered features we associate with modern highways. It was little more than a dirt wagon track in many places, crossing creeks and rivers sometimes on narrow wooden bridges, with stretches impassable in wet weather or blocked by livestock fences. The highway officially began at Times Square (the convoy had started in Coney Island to get the Atlantic in the photos), winding from there through a dozen states until it ended, after a ferry ride from Oakland, at Lincoln Park on San Francisco’s northwest corner. The length of the trip, according to that year’s official Lincoln Highway guide, was 3,384 miles.

1916-Lincoln Highway Route Official Road Guide

The Lincoln Highway had been formally declared open by its backers—a private group, not a government agency—with a coordinated series of ceremonies along the route on Oct. 31, 1913, though it was then a highway more in aspiration than in reality: an idea stretched across the continent and given a name. So it remained in the summer of 1915, when this handful of cars set out to trudge across its entire length.

At the head of the motorcade was a new Stutz touring car: crisp white paint with blue trim, crowned fenders swooping down to wide running boards, soft black leather Victoria top. The Stutz was piloted by Henry C. Ostermann, Indianan by birth, cross-country traveler by proclivity. This was at least his sixth transcontinental drive. In the car with Ostermann were his wife Babe Bell, his assistant Edward Holden, and a silent passenger that was in many ways the most important member of the party: a motion picture camera.

The convoy wasn’t making its way westward simply to experience the sights and thrills of the open road. Henry Ostermann was the vice president and field secretary of the Lincoln Highway Association, the organization that raised funds for the creation of the road, chose its route, and promoted its use and continued improvement. Ostermann and his LHA team were filming their trip from start to end. The film would be a publicity tool for the association, as would the tour itself. The LHA gave advance notice to towns along the route, which supplied (privately raised) funding for the journey in return for the attention they hoped the film would bring them. They also provided crowds, who assembled at monuments, like the Lincoln memorial at the Gettysburg National Cemetery, and lined the route for parades, as they did in South Bend, Indiana.

From Gettysburg to Greensburg, Lima to Ligonier, Clinton to Kearney, Salt Lake to Sacramento, the LHA party filmed their way across the country through spring and into summer. The convoy arrived in San Francisco on Aug. 25, driving a couple of cars into the breaking Pacific surf on Ocean Beach to bookend the trek. The journey, which lasted longer than usual for a cross-country drive even in this time of rough, muddy, irregular roads, had taken 102 hard days and generated around 10,000 feet of film.

Photo by Dennis E. Horvath

You might be setting out on a long journey of your own this Thanksgiving holiday—hopefully not one lasting 3,384 miles spread over 102 days, though it may at times feel that way. As you travel some of America’s nearly 4.1 million miles of paved public roads, you might offer quiet thanks, or a muttered curse, to Dwight Eisenhower, whose name is on the Interstate System. But the story of how we got from there to here is far more complicated than the work of a single president. It’s largely a story of how the automobile industry convinced government to pay for the roads it needed to move product, and it stretches all the way back to Henry Ostermann’s 100-year-old road trip movie.

* * *

The Lincoln Highway is often awarded the title of first transcontinental automobile highway in the United States, which is true, mostly. Other groups had been pushing different coast-to-coast routes before Indiana businessman Carl Fisher led the formation of the Lincoln Highway Association in 1912. Its New York to San Francisco route was only one of several long-distance “auto trails” created in the United States in the 1910s by private associations.

What made the Lincoln Highway special was the extraordinary promotional flair of its backers. Its 1913 dedication ceremonies kicked off a long run of vigorous public relations by the association, including annual guidebooks, newspaper and magazine stories, and a wide assortment of other material distributed across the country. The 1915 motion picture convoy was audacious, but hardly out of character.

San Francisco Examiner 1915

Ostermann and crew had created their film for a ready-made audience. San Francisco was hosting a world’s fair: the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. The LHA film ran in San Francisco from early September until the world’s fair closed on Dec. 4. It then reversed the journey of its creation and headed east back across the country, playing to large crowds in the same towns where Ostermann had filmed on his way west. Packed into theaters and exhibition halls, these small-town audiences were treated to views of the great breadth of their nation, like those described in the March 10, 1916, edition of the Gettysburg Star and Sentinel:

In Cedar Rapids, Iowa, which is the home of Quaker Oats, a shower of oats was the feature. At Ames, Iowa, the state college turned out its 400 cadets for the picture. Omaha, Nebraska, was especially illuminated at night for the Lincoln Highway camera man. Grand Island, Nebraska, which is the second largest horse market in the world, had 2,000 horses for the camera. Rough-riding of the most spectacular kind was scheduled for Cheyenne, Wyoming, where the great frontier celebration was held. At Laramie the cattle industry was depicted. Rawlins, Wyoming, indicated its chief industry by an enormous pyramid of wool; the famous trout streams of the vicinity were also shown, together with a record catch of finny beauties.

These scenes might read as prosaic today, but a century ago, the Lincoln Highway movie was a true spectacle. The LHA’s official history, as recorded in a 1935 book The Lincoln Highway: The Story of a Crusade That Made Transportation History, tells us the film “met with high enthusiasm everywhere” (local newspaper items from the time corroborate what might otherwise be self-serving puffery). The film went on to turn a small profit for the association after they licensed it for exhibition by others. As the LHA history exclaims, “Verily, as propagandists these men left nothing to be desired!”

Ostermann and crew hoped the film would show these audiences how wonderful it was to have a road linking the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, but also what rough shape that road was in, and how difficult, though colorful, the crossing was. It was road publicity, but also—as the LHA itself acknowledged—propaganda, meant to plant a suggestion in the minds of its viewers: Shouldn’t this road, and maybe others like it, be paved and improved in the future? Wouldn’t that be great for America?

What the LHA representatives probably didn’t mention at the screenings of their film was how great more road-building would have been for the men behind the Lincoln Highway. At the time of the association’s creation, founder Carl Fisher had a near-monopoly on the manufacture of automotive headlights in America. Henry Joy, the LHA’s first president, was the head of Packard Motor Car Company. Another major backer and later president of the association was Frank Seiberling, co-founder and president of Goodyear Tire. William C. Durant, co-founder of General Motors, donated $100,000 toward the construction of a segment of particularly difficult road in Nevada. Other supporters included the heads of Hudson Motor Car Company, Willys-Overland Motors, and Lehigh Cement.

These men may very well have believed that new and improved roads across America would be good for the country. They certainly knew it would be good for their businesses. Fisher is reported to have said to his association colleagues, “The automobile won’t get anywhere until it has good roads to run on.” And they knew that getting those good roads meant securing public support. In a letter to a friend in 1912, Carl Fisher wrote, “[T]he highways of America are built chiefly of politics.” Despite Fisher’s early hopes that his transcontinental road would be a graded and paved from end to end, he and his LHA colleagues realized within a year of starting that they could never gather through private donations the millions of dollars needed for such a project. The LHA understood that building roads at any meaningful scale would require government funding. Their work had exposed them to the wide variation in the willingness of individual cities, counties, and states to spend money on roads. That left the federal government.

By the time the LHA decided to try its hand at filmmaking in 1915, advocates for federal highway funding were a minority, and a fractious one. Some road-building lobbying groups wanted money for local “farm-to-market” roads, others for “touring” roads and interstate routes. Amid disagreement within the road lobby, and with car ownership rates still low, highway bills submitted annually by sympathetic congressmen foundered in committee or expired quietly on a clerk’s desk. (The road advocates’ only tangible federal success had been a $500,000 appropriation in 1912 toward an experimental post-road improvement program that eventually built only 455 miles of road.)

As the LHA film was traveling back across the country in early 1916, Congress was debating a new road-funding bill. This time, everything clicked for the road lobby. Among other changes in the legislative environment, a new consensus had formed, spearheaded by the American Association of State Highway Officials. The Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, based largely on language drafted by AASHO, passed Congress in late June. President Woodrow Wilson, signed the bill on July 11, 1916.

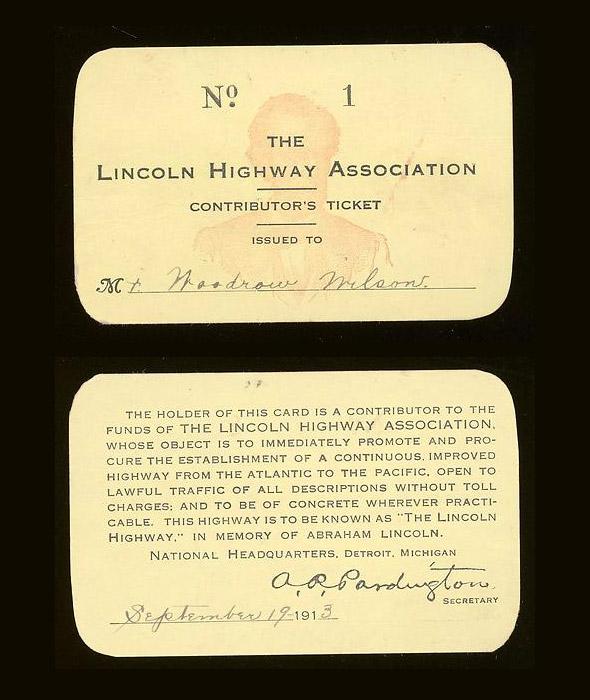

It would be a stretch to say that the Lincoln Highway convoy and its film tour broke the legislative logjam that had prevented earlier attempts to create a federal highway program, but it did have an effect. President Wilson had personally joined the Lincoln Highway Association (and had received membership ticket Number One). By virtue of its geographic reach and robust publicity, the LHA helped spread the gospel of good roads and interstate highways in ways that other groups could not.

NMAH, Transportation Collections

It’s also worth noting that the AASHO legislative proposal that became the 1916 highway bill had been developed in Sept. 1915 at the Pan-American Road Congress held in Oakland, just across San Francisco Bay from where Ostermann was showing his movie. The head of the AASHO working group was Thomas MacDonald, Iowa State Highway Engineer and long-time supporter of the Lincoln Highway work in his home state. He would certainly have known about the LHA film being shown in San Francisco. It’s not hard to imagine MacDonald and his colleagues hopping on a ferry across the bay and riding a streetcar to the exposition to find some cinematic inspiration before returning to their legislative drafting.

* * *

The work of the Lincoln Highway Association in advocating for highway improvements did not end with the 1915 film or with the passage of the 1916 Federal Aid Road Act. (In fact, America’s entry into World War I rerouted most of the money, men, and materials that might otherwise have built roads under that act.) Henry Ostermann would direct no more films, but he would lead more cross-country tours with an eye toward promotion. In 1917, he piloted a convoy of Packard trucks that had been purchased by the US Army, guiding them from Detroit to a port in Baltimore, headed from there to Europe for the Great War.

In 1919, Ostermann led another convoy of Army vehicles, this time westward from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco, most of it along the Lincoln Highway. This convoy of around 80 vehicles carried 282 men and the supplies and equipment necessary to support them, but little else of material value. It was, like the 1915 convoy, largely a publicity effort, designed to encourage the construction of transcontinental roads and spur interest in the use of motor vehicles. It did so largely by proving how difficult it was to get a convoy of 80 vehicles and 282 men across the country. The trip was by all accounts a horrible slog: trucks mired in mud, slid into ditches, sank into sand, and broke down repeatedly as they limped their way to San Francisco over 62 days.

Despite the physical difficulty of the trip—or quite possibly because of it—the 1919 Army convoy was a success in exactly the way that the Lincoln Highway Association had hoped when they lent Henry Ostermann to what was ostensibly a military endeavor. The trip’s difficulties helped convince Congress to pass the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921, under which federally funded highway construction in America began in earnest.

The convoy had longer-lasting effects, too. Among the travelers in that 1919 party was Lt. Col. Dwight Eisenhower, who took the lessons of that trip (along with war-time observations in Germany) to the White House 30-some years later, where he pushed for and signed the legislation that began construction of the Interstate Highway System that bears his name. The work of the LHA and Henry Ostermann undergirds every mile of that modern system.

All told, Ostermann crossed the country 20 times in his life, every time by car. He probably would have completed many more, had he not died in June 1920. Driving outside of Tama, Iowa, he attempted to pass a slower car, hit a patch of loose earth left from recent roadwork, and lost control. His car rolled twice, and he was crushed. He was 44. The road that did him in was a segment of the Lincoln Highway.

Henry Ostermann died before America’s great highway building boom, as did Carl Fisher and many of the others who created the Lincoln Highway and the other early auto trails. But many more took up their example. The auto, oil, rubber, and construction industries would remain the prime movers behind highway lobbying in the U.S., formalizing those efforts with the creation in 1932 of the National Highway Users Conference, spearheaded by Alfred P. Sloan of General Motors. The LHA’s publicity efforts also inspired those who, nearly a half-century after Ostermann’s directorial debut, created highway advocacy films like Give Yourself the Green Light (General Motors), Freedom of the Open Road (Ford), Highway Hearing (Dow Chemical), and many more. These were all part of a great push leading up to the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956—the legislation that created the Interstate Highway System.

The 1915 Lincoln Highway film wasn’t as long-lived as the pro-highway consensus it helped build. Like nearly all early motion pictures, it was printed on nitrate stock, which decomposes into a gummy mess, then into powder, if it doesn’t explosively auto-ignite first. We can still see a bit of it in one of those later highway films: a 1957-58 Disney production called “Magic Highway USA”. At around the 18-minute mark in this movie rosily extolling the virtues of the American highway, there are about 30 seconds of footage from the primogenitor of the genre. This is the only known remnant of the Ostermann film.

A century ago, Henry Ostermann drove across the country with a motion picture camera, hoping to influence the future American of transportation. And it worked. We got the transcontinental touring routes; we got the farm-to-market roads. We also got freeway-abetted suburban sprawl and neighborhoods gutted or divided by highways bulldozed through our cities. More Americans are coming to see the downsides of an auto-focused transportation system and the mixed record of what our highways have done for (and to) the country—but we haven’t stopped using them. We drive tens of billions of miles on our highways every year, our tires rolling over the sometimes bumpy legacy of Henry Ostermann, Carl Fisher, and the Lincoln Highway Association. You can’t see their 100-year-old road trip movie anymore, but you can see its impact. Just look out the window of your car.