On Vox Wednesday, Sarah A. Chrisman writes about the decision she and her husband have made to conduct their lives as if they were late-19th-century Americans. The couple lives in their home, which was built in 1888, without the benefit of 21st-century conveniences, eschewing refrigeration and modern electric lighting. They also wear period dress, happily pedal around town on reproduction bicycles, and clean their teeth with a toothbrush made of “natural boar bristles.”

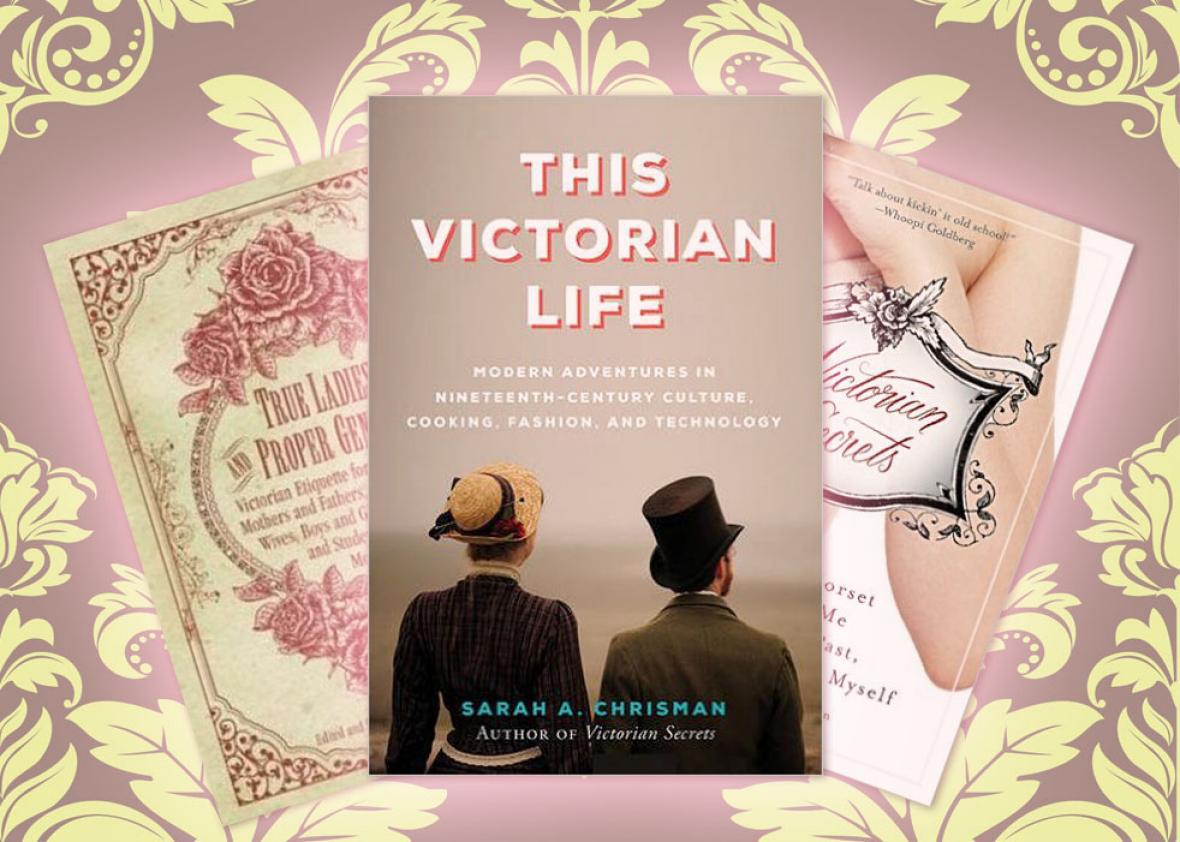

There are many irritating things about this article. The irony of congratulating yourself on sticking to 1880s technology in a piece circulated on the Internet is an obvious place to start. The author has also published two books, and will publish a third this fall; this feat was presumably accomplished with at least some assistance from computers and the Web. Certainly the note at the bottom of the Vox article directing readers to her website provoked its share of raised eyebrows.

More irritating still is Chrisman’s apparent confidence that avoiding certain contemporary technologies, and dressing in period garb, has provided her with a palpable sense of what it was like to live in the 19th century. Chrisman writes about the physical sensations she gets from living in Victorian clothing:

Features of posture, movement, balance; things as subtle as the way my ankle-length skirts started to act like a cat’s whiskers when I wore them every single day. I became so accustomed to the presence and movements of my skirts, they started to send me little signals about my proximity to the objects around myself, and about the winds that rustled their fabric—even the faint wind caused by the passage of a person or animal close by.

Chrisman may well have a better sense than you or I about how it feels to wear such a skirt. But donning antique clothing doesn’t transport the wearer to times past—it doesn’t even necessarily give you a great sense of what it was like to wear such clothes in the 1880s. Wearing a corset as an adult, out of choice, as Chrisman does, will come with a particular set of physical sensations. Wearing a corset from girlhood on; being told you must wear a corset or you won’t be womanly; or wearing a corset while you have tuberculosis—all of these Victorian relationships to this garment were particular to their time. Chrisman doesn’t say so, but I assume that she and her husband avail themselves of modern medicine; in any event they’d be hard pressed to catch many of the now-rare diseases that afflicted the Victorians. The re-creation of the physical feeling of living in the late 19th century can only ever be a partial one.

The question of health brings me to perhaps the greatest fallacy inherent in the Chrismans’ method of “living history.” The “past” was not made up only of things. Like our own world, it was a web of social ties. These social ties extended into every corner of people’s lives, influencing the way people treated each other in intimate relationships; the way disease was passed and treated; the possibilities open to women, minorities, and the poor; the whirl of expectations, traditions, language, and community that made up everyday lives. Material objects like corsets or kerosene lamps were part of this complex web, but only a part.

The Chrismans also take a preposterously rosy view of their favorite era, choosing to recall the quaint elements of Victorian life and ignore its difficulties. Chrisman complains that people are sometimes cruel to her and her husband for their period predilections: “We live in a world that can be terribly hostile to difference of any sort. Societies are rife with bullies who attack nonconformists of any stripe.” This was true for their precious late-19th-century decades as well. Ask Ida B. Wells, driven out of Memphis in 1892 for protesting lynching, or a Chinese laborer prohibited from entering the United States under the terms of the 1882 Exclusion Act.

Even if an 1890s version of Chrisman, or of her husband, would have lived a comfortable and privileged life, they could not have lived it in a vacuum, as the 2010s Chrismans are attempting to do. The social world around them would have demanded that they take some kind of a stance on the mores and ideologies dominant at the time. Would you accept the fact that immigrant children in your town worked in a factory, or protest against it? If you’re female, would you drop your education when your family thought you’d had enough? These are choices that the sealed world of the Chrismans’ re-enactment doesn’t demand of them.

Chrisman writes that she and her husband have retreated from the present in part to escape the incomprehensible technologies that now govern our lives, and to avoid the disconnection from the natural world that comes with modernity. As historian Shirley Wajda noted on Twitter, these are—ironically enough—quite similar to worries that late-Victorian Americans also had. In his influential book No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture, 1880–1920, historian T.J. Jackson Lears describes the way that elites of the era were increasingly anxious about the pace and demands of modern life. The Chrismans are, in fact, more Victorian than they realize.

That’s because Chrisman probably hasn’t read T.J. Jackson Lears. She argues that primary sources are better than “commentaries” for a person wanting to know what the late Victorian period was like in the United States. This might seem to be an admirable stance—what historian would object to the impulse to go straight to the source?—if it weren’t paired with a confused disdain for the historical profession. She writes:

There is a universe of difference between a book or magazine article about the Victorian era and one actually written in the period. Modern commentaries on the past can get appallingly like the game ‘telephone’: One person misinterprets something, the next exaggerates it, a third twists it to serve an agenda, and so on. Going back to the original sources is the only way to learn the truth.

This is an unfair characterization of professional historians, who generally acknowledge the impossibility of total objectivity while trying hard to be as clear-minded and fair as possible. It also betrays a hopelessly naive understanding of the historical record, which is, itself, incomplete and “twisted” by the agendas of those who have produced, saved, and recirculated its texts. The primary sources the Chrismans choose to read made it to the present day because they held some kind of value for the intervening generations. The couple finds its period magazines on Google Books, that redoubtable Victorian technology. It seems not to have crossed their minds that a series of human decisions resulted in the digitization of those magazines and not others, and that those decisions are themselves a type of commentary.

On the contrary, the Chrismans seem to deny that their experience of the past is mediated in any way, preferring to cast themselves instead as pure vessels of late-19th-century life. But everyone who reads about, thinks about, and writes about the past is, inevitably, an interpreter. There are good and careful interpreters, and bad ones. Part of the job of the person who is in love with history is to recognize the difference.