This article supplements Episode 5 of The History of American Slavery, our inaugural Slate Academy. Please join Slate’s Jamelle Bouie and Rebecca Onion for a different kind of summer school. To learn more and to enroll, visit Slate.com/Academy.

Excerpted from The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism by Edward E Baptist. Published by Basic Books.

In 1800, French traveler Pierre-Louis Duvallon prophesized that New Orleans was “destined by nature to become one of the principal cities of North America, and perhaps the most important place of commerce in the new world.” Projectors, visionaries, and investors who came to this city founded by the French in 1718 and ceded to the Spanish in 1763 could sense the same tremendous possible future.1

Yet powerful empires had been determined to keep the city from the United States ever since the 13 colonies achieved their independence. Between 1783 and 1804, Spain repeatedly revoked the right of American settlers further upriver to export their products through New Orleans. Each time they did so, western settlers began to think about shifting their allegiances. Worried U.S. officials repeatedly tried to negotiate the sale and cession of the city near the Mississippi’s mouth, but Spain, trying to protect its own empire by containing the new nation’s growth, just as repeatedly rebuffed them.2

Spain’s stubborn possession of the Mississippi’s mouth kept alive the possibility that the United States would rip itself apart. Yet something unexpected changed the course of history.

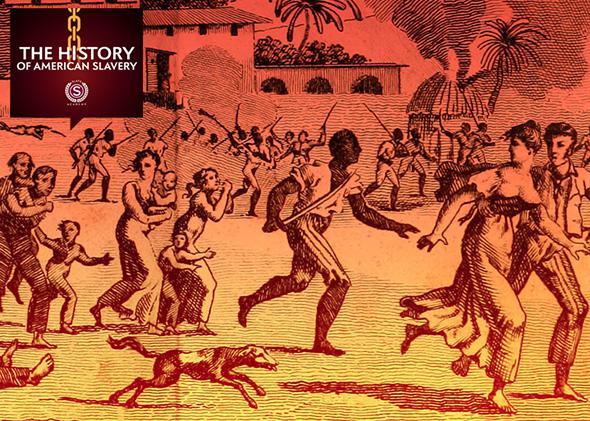

In 1791, Africans enslaved in the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue exploded in a revolt unprecedented in human history. Saint-Domingue, the western third of the island of Hispaniola, was at that time the ultimate sugar island, the imperial engine of French economic growth.* But on a single August night, the mill of that growth stopped turning. All across Saint-Domingue’s sugar country, the most profitable stretch of real estate on the planet, enslaved people burst into the country mansions. They slaughtered enslavers, set torches to sugar houses and cane fields, and then marched by the thousand on Cap-Francais, the seat of colonial rule. Thrown back, they regrouped. Revolt spread across the colony.3

By the end of the year thousands of whites and blacks were dead. As the cane fields burned, the smoke blew into the Atlantic trade winds. Refugees fled to Charleston, already burdened by its own fear of slave revolt; to Cuba; and to all the corners of the Atlantic world. They brought wild-eyed tales of a world turned upside down. Europeans, in the throes of epistemological disarray because of the French Revolution’s overthrow of a throne more than a millennium old, reacted to these events with a different but still profound confusion. Minor slave rebellions were one thing. Total African victory was another thing entirely—it was so incomprehensible, in fact, that European thinkers, who couldn’t stop talking about the revolution in France, clammed up about Saint-Domingue. The German philosopher Georg Hegel, for instance, who was in the process of constructing an entire system of thought around the idealized, classical image of a slave rebelling against a master, never spoke of the slave rebellion going on in the real world. Even as reports of fire and blood splattered every weekly newspaper he read, he insisted that African people were irrelevant to a future that would be shaped by the newly free citizens of European nation-states.4

Yet the revolution in Saint-Domingue was making a modern world. Today, Saint-Domingue is called Haiti, and it is the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere. But Haiti’s revolutionary birth was the most revolutionary revolution in an age of them. By the time it was over, these people, once seemingly crushed between the rollers of European empire, ruled the country in which they had been enslaved. Their citizenship would be (at least in theory) the most radically equal yet. And the events they pushed forward in the Caribbean drove French revolutionaries in the National Assembly to take steadily more radical positions—such as emancipating all French slaves in 1794, in an attempt to keep Saint-Domingue’s economic powerhouse on the side of the new leaders in Paris. Already, however, the slave revolution itself had killed slavery on the island. An ex-slave named Toussaint Louverture had welded bands of rampaging rebels into an army that could defend their revolution from European powers who wanted to make it disappear. Between 1794 and 1799, his army defeated an invasion of tens of thousands of anti-revolutionary British Redcoats.5

By 1800, Saint-Domingue, though nominally still part of the French Republic, was essentially an independent country. In his letters to Paris, Toussaint Louverture styled himself the “First of the Blacks.” He was communicating with a man rated the First in France—Napoleon Bonaparte, first consul of the Republic, another charismatic man who had risen from obscure origins. Napoleon, an entrepreneur in the world of politics and war, rather than business, used his military victories to destroy old ways of doing things. Then he tried to create new ones: a new international order, a new economy, a new set of laws, a new Europe—and a new empire. But after he concluded the Peace of Amiens with Britain in 1800, the ostensible republican became monarchical. He set his sights on a new goal: restoring the imperial crown’s finest jewel, the lost Saint-Domingue. In 1801, he sent the largest invasion fleet that ever crossed the Atlantic, some 50,000 men, to the island under the leadership of his brother-in-law Charles LeClerc. Their mission was to decapitate the ex-slave leadership of Saint-Domingue. “No more gilded Africans,” Napoleon commanded. Subdue any resistance by deception and force. Return to slavery all the Africans who survived.6

Napoleon had also assembled a second army, and he had given it a second assignment. In 1800, he had concluded a secret treaty that “retroceded” Louisiana to French control after 37 years in Spanish hands. This second army was to go to Louisiana and plant the French flag. And at 20,000 men strong, it was larger than the entire U.S. Army. Napoleon had already conquered one revolutionary republic from within. He was sending a mighty army to take another by brute force.7

In Washington, Jefferson heard rumors of the secret treaty. To keep alive his utopian plans for a westward-expanding republic of independent white men, he was already compromising with slavery’s expansion. Now he saw another looming choice between hypocritical compromise and destruction. As Jefferson now instructed his envoy to Paris, Robert Livingston, “there is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans.” Jefferson had to open the Mississippi one way or another. Should a French army occupy New Orleans, wrote Jefferson, “we must marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation.”8

Napoleon had his own visions. He ignored Jefferson’s initial offer for the city at the mouth of the Mississippi. So the president sent future president James Monroe with a higher bid: $10 million for the city and its immediate surroundings. Yet, in the end, Paris would not decide this deal. When Le- Clerc’s massive army had disembarked in Saint-Domingue, the French found Cap-Francais a smoldering ruin, burned as part of scorched-earth strategy. LeClerc successfully captured Toussaint by deception and packed him off to France to be imprisoned in a fortress in the Jura Mountains. Resistance, however, did not cease. The army Louverture had built began to win battles over the one Napoleon had sent. French generals turned to genocide, murdering thousands of suspected rebels and their families. The terror provoked fiercer resistance, which—along with yellow fever and malaria—killed thousands of French soldiers, including LeClerc.

By the middle of 1802, the first wave of French forces had withered away. Napoleon reluctantly diverted the Louisiana army to Saint-Domingue. Then this second expedition to the Caribbean was also destroyed. So even as Toussaint Louverture shivered in his cell across the ocean, the army he left behind became the first to deal a decisive defeat to Napoleon’s ambitions. “Damn sugar, damn coffee, damn colonies,” the first of the whites was heard to grumble into his cup at a state dinner. On April 7, 1803, Louverture’s jailer entered the old warrior’s cell and found the first of the blacks seated upright, dead in his chair. The same day, Monroe’s ship hove into sight of the French coast. And on April 11, before Monroe’s stagecoach could reach Paris, a French minister invited Livingston to his office.9

Napoleon’s minion shocked Livingston almost out of his knee breeches with an astonishing offer: not just New Orleans, but all of French Louisiana—the whole west bank of the Mississippi and its tributaries. Now the United States was offered—for a mere $15 million—828,000 square miles, 530 million acres, at 3 cents per acre. This vast expanse doubled the nation’s size. Eventually the land from the Louisiana Purchase would become all or part of 15 states. It still accounts for almost one-quarter of the surface area of the United States. By the late 20th century, Jefferson’s windfall would be feeding much of the world. One imagines that Livingston found it hard to hold his poker face steady. He immediately agreed to the deal.10

So it was that as 1804 began, two momentous ceremonies took place. Each formalized the consequences of the successful overthrow, by enslaved people themselves, of the most profitable, most fully developed example of European imperial sugar slavery. One of the ceremonies took place in Port-au-Prince and was held by a gathering of leaders who had survived the Middle Passage, slavery, revolution, and war. On Jan. 1, they proclaimed the independence of a new country, which they called Haiti—the name they believed the original Taino inhabitants had used before the Spaniards killed them all. Although the country’s history would be marked by massacre, civil war, dictatorship, and disaster, and although white nations have always found ways to exclude Haiti from international community, independent Haiti’s first constitution created a radical new concept of citizenship: only black people could be citizens of Haiti. And who was black? All who would say they rejected both France and slavery and would accept the fact that black folks ruled Haiti. Thus, even a “white” person could become a “black” citizen of Haiti, as long as he or she rejected the assumption that whites should rule and Africans serve.11

Not only did Haitian independence finish off Napoleon’s schemes for the Western Hemisphere, but it also sounded the knell for the first form of New World slavery. On the sugar islands, productivity had depended on the continual resupply of captive workers ripped from the womb of Africa. Many Europeans who had not been convinced of the African slave trade’s immorality were now convinced that it had brought destruction upon Saint-Domingue, by filling it full of angry men and women who had tasted freedom at one point in their lives. British anti-slave-trade activism, frightened into a pause in 1791 by heads severed by the Saint-Domingue rebels and Paris guillotines, became conventional London wisdom. In 1807, the British Parliament passed a law ending the international slave trade to its empire. In the near future, Britain’s government and ruling class, confident that their own abolition of the trade had provided them with what historian Christopher Brown has aptly called “moral capital,” would use the weight of their growing economic influence to push Spain, France, and Portugal toward abolishing their own Atlantic slave trades.12

Meanwhile, the Haitian Revolution had made it possible for the United States to open up the Mississippi Valley to the young nation’s internal slave trade. About 10 days before the declaration of independence in Port-au-Prince, on Dec. 22, 1803, Louisiana’s new territorial governor had accepted the official transfer of authority in New Orleans. American acquisition depended on the sacrifices of hundreds of thousands of African men, women, and children who in Saint-Domingue rose up against the one social institution whose protection appeared to be written into the U.S. Constitution—the enslavement of African people. This reliance on the success of the Haitian Revolution was a profound irony. Jefferson did not acknowledge that Toussaint’s posthumous victory made the nation’s—and slavery’s—expansion possible. The only voice pointing out that the republican president was an emperor without clothes came from Jefferson’s old rival Alexander Hamilton, who wrote that “to the deadly climate of St. Domingo, and to the courage and obstinate resistance made by its black inhabitants are we indebted. … [The] truth is, Bonaparte found himself absolutely compelled”—and not by Jefferson—“to relinquish his daring plan of colonizing the banks of the Mississippi.”13

Even today, most U.S. history textbooks tell the story of the Louisiana Purchase without admitting that slave revolution in Saint-Domingue made it possible. And here is another irony. Haitians had opened 1804 by announcing their grand experiment of a society whose basis for citizenship was literally the renunciation of white privilege, but their revolution’s success had at the same time delivered the Mississippi Valley to a new empire of slavery. The great continent would incubate a second slavery exponentially greater in economic power than the first.

*Correction, Aug. 7, 2015: This article originally misstated that at the outset of the Haitan Revolution Saint-Domingue occupied the eastern third of Hispaniola. It occupied the western third.

Excerpted with permission from The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism by Edward E Baptist. Available from Basic Books, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2014.

1. Berquin-Duvallon, Travels in Louisiana, 35–37.

2. Alexander DeConde, This Affair of Louisiana (New York, 1976), 61– 62, 107–126; William Plumer, William Plumer’s Memorandum of Proceedings in the U.S. Senate,1803–1807, ed. Edward Sommerville Brown (Ann Arbor, MI, 1923).

3. Carolyn Fick, The Making of Haiti: The St. Domingue Revolution from Below (Knoxville, TN, 1990).

4. Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston, 1995); Susan Buck-Morss, “Hegel and Haiti,” Critical Inquiry 26 (2000):821–865; Alfred N. Hunt, Haiti’s Influence on Antebellum America: Slumbering Volcano in the Caribbean (Baton Rouge, LA, 1988).

5. C. L. R. James, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint Louverture and the San Domingo Revolution (New York, 1963).

6. Stephen Englund, Napoleon: A Political Life (New York, 2004); Laurent DuBois, Avengers of the New World (New York, 2004); Robin Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery (London, 1988).

7. Roger Kennedy, Mr. Jefferson’s Lost Cause: Land, Farmers, Slavery, and the Louisiana Purchase (New York, 2003).

8. Jefferson to Robert Livingston, April 18, 1802; Jon Kukla, A Wilderness So Im- mense: The Louisiana Purchase and the Destiny of America (New York, 2003), 235–259.

9. DeConde, Affair of Louisiana, 161–166.

10. P. L. Roederer, Oeuvres du Comte P. L. Roederer (Paris, 1854), 3:461; Comté Barbé-Marbois, The History of Louisiana: Particularly of the Cession of That Colony to the United States of America, trans. “By an American Citizen (William B. Lawrence)” (Philadelphia, 1830), 174–175, 263–264.

11. Dubois, Avengers of the New World, 297–301.

12. Christopher Brown, Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism (Chapel Hill, NC, 2006).

13. DeConde, Affair of Louisiana, 205–206; Jared Bradley, ed., Interim Appoint- ment: William C. C. Claiborne Letter Book, 1804–1805 (Baton Rouge, LA, 2003), 13; Alexander Hamilton, in New-York Evening Post, July 5, 1803, Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 26:129 –136. An exception to historians’ cover-up: Henry Adams, History of thAdministrations of Jefferson and Madison (New York, 1986 [Library of America]), 1:2, 20 –22. Cf. Edward E. Baptist, “Hidden in Plain View: Haiti and the Louisiana Purchase,” in Elizabeth Hackshaw and Martin Munro, eds., Echoes of the Haitian Revolution in the Modern World (Kingston, Jamaica, 2008).