Excerpted from Lincoln’s Body: A Cultural History by Richard Wightman Fox, out now from W. W. Norton & Co.

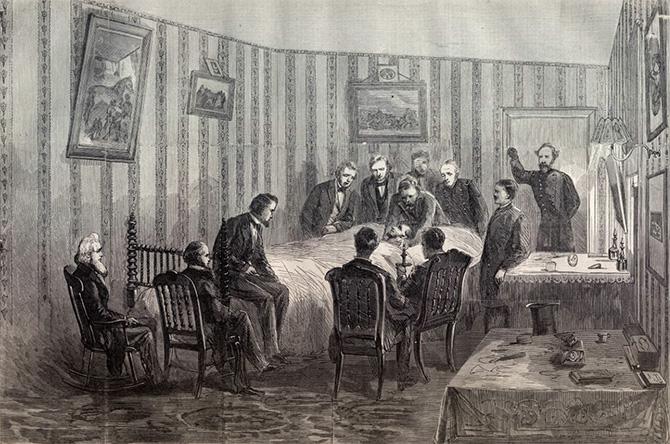

When Lincoln breathed his last on Saturday morning, April 15, 1865, his wife was ensconced in the front parlor of the Petersen House. Edwin Stanton, secretary of war, had invited her to the deathbed for a brief visit about 20 minutes before the end, and that may have been the last time she saw her husband’s body.

When she departed from the Petersen House, descending the front steps and gripping the curved metal railing still in place to this day, she looked up at Ford’s Theatre, cursed it, and then climbed into her closed carriage alongside her son Robert and her friend Elizabeth Dixon. Back at the White House, she ascended to the second-floor living quarters and stayed there for five straight weeks.

Mary’s lengthy White House isolation gave Northern mourners a chilling crystallization of their own suffering. Until April 20, she did not even sit up in bed. Having been denied any semblance of a family deathbed scene at the Petersen House—Stanton refusing to let her bring in young Tad, or to let her mourn as inconsolably as she had wished—she settled into a deafening public silence.

In doing so, she unintentionally bestowed a great gift on the American people. She handed her husband’s body over to the body politic. The people’s grief, and the people’s martyr, would take precedence over the family’s mourning and family’s loved one. Of course, family metaphors shaped the people’s perception of Lincoln during the war and after his death. The Union’s soldiers especially called him Father Abraham, but many others insisted that losing him felt exactly like losing a member of their family.

Illustration courtesy of Harper’s Weekly via Wikipedia Commons

Mrs. Lincoln’s withdrawal from the physical body created a vacuum that Stanton gladly filled. Having failed to protect his friend in life, he would now micromanage him in death, surrounding the corpse with the military guard that the living president had so often eluded and keeping track of which individuals were permitted to touch him or his coffin. For all he knew, Confederate sympathizers might attempt to desecrate the remains.

Stanton left no detail to chance. Only hours after Lincoln’s death, it was apparently he who decided what to do about the ugly bruises under Lincoln’s eyes. The embalmers’ impulse was to make him look “natural,” said the New York Herald, just as he looked in “the portraits of the late president, so familiar to the people”: a “broad brow and firm jaw” and “a placid smile upon the lips.” That would require them “to remove the discoloration from the face by chemical process.” But the secretary of war insisted on preserving the purple splotches as “part of the history of the event … an evidence to the thousands who would view the body when it shall be laid in state, of the death which this martyr to his ideas of justice and right had suffered.”

Stanton completed Lincoln’s funeral itinerary on April 19, two days before the train’s departure.

Mary Lincoln beseeched Stanton to send Lincoln home by the most direct path—west across Pennsylvania from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh and on to the Midwest—thus avoiding the lengthy northern trek through New Jersey and New York. But Stanton held out. The funeral journey would qualify as a truly Union experience. The train carrying Lincoln’s body would pass through all five of the most populous northern states—Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois—and would miss only one state (Massachusetts) containing more than 1 million inhabitants. Mrs. Lincoln fought tooth and nail for just one thing: the particular burial plot in Oak Ridge Cemetery, two miles outside of Springfield, Illinois, that would receive her husband’s remains.

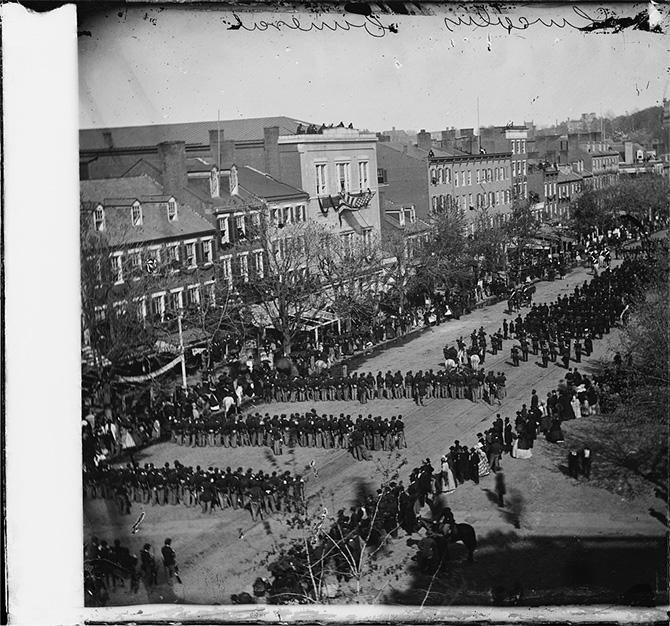

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Lincoln’s body held up well through the first stops of the funeral train: Baltimore; Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; and Philadelphia. During the 20-hour marathon viewing in Philadelphia, perhaps 150,000 people passed by his coffin after waiting for up to five hours. Lincoln’s old Springfield friend Ozias Hatch, riding on the train as part of the Illinois delegation, noted some facial splotches but found him looking “quite natural.” So did the Philadelphia Inquirer, which observed “a natural, placid, peaceful expression.”

The tide began turning for Lincoln’s corpse after the marathon viewing in Manhattan, hard on the heels of the first one in Philadelphia. In New York City the body was exposed to the air for 23 straight hours—from 1 p.m. on Monday, April 24, to noon the next day. Among the thousands, black and white, who shuffled past the bier, seeking to soak in Lincoln’s face and upper torso, was 17-year-old Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the future sculptor. Having gazed at the president’s flesh, the teenager walked out of City Hall and got back in line, waiting hours more to see the corpse a second time.

As the train left New York City for Albany, New York, on Tuesday afternoon, newspaper readers got alarming reports about the condition of the body. The New York Times claimed the body “had very materially altered” while on view in the city. “Dark as was the face before, and unearthly, it was, at 11 o’clock [Monday night], nearly five shades darker. The dust had gathered upon the features, the lower jaw somewhat dropped, the lips slightly parted, and the teeth visible. It was not a pleasant sight.” The condition of the body made it “doubtful,” said the Times, that additional public viewings could take place.

Poet and editor William Cullen Bryant’s New York Evening Post went further, declaring, “It is not the genial, kindly face of Abraham Lincoln; it is but a ghastly shadow.” Those seeing “our martyred president for the first time” would get “but a poor idea of his homely, kind, intelligent countenance.” His now “sunken, shrunken features,” in Bryant’s estimation, meant that New Yorkers would surely be the last to “gaze upon the upturned face of President Lincoln.”

When the train reached Albany late Tuesday night, embalmer Charles Brown and undertaker Frank Sands handed a firm denial to the press: “No perceptible change has taken place in the body of the late President since it left Washington” (the word “perceptible” appeared to concede that some change might have occurred but that skilled hands could obscure it with powder). Citizens in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois could breathe easier; they would get to see Lincoln’s remains after all.

But dueling claims about the condition of the corpse now colored the rest of the journey. Who was right—Brown and Sands or the New York City papers? Had no perceptible change taken place, or had “the embalmer’s labors,” as the New York World contended, been “set at naught by the organic forces with which the King of Terrors completes the sentence [of] ‘Dust to dust’ ”? Reporters on the scene in Albany added support to the World’s vivid speculation by noting that Lincoln’s face was “evidently growing yet darker in spite of the chemicals used as preservatives”; “the kindly face is discoloring.”

Intensifying alarm about the body’s state gave the last week of the funeral journey a very different feel from that of its first five days. From April 21 to 25, officials debated how to maximize spectatorship and maintain order. Now, as they managed a public still desperate to lay eyes on Lincoln, they fretted about keeping spectators locked into a proper posture of mourning. Journalists began wondering whether the corpse’s decay was altering the makeup of the crowds. Charles Page soon decided that it was: Some mourners were now lining up out of “morbid curiosity” alone.

Photo by Samuel Montague Fassett. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Once the train made it to Buffalo, New York, after a grueling 15-hour trek covering 300 miles, the Chicago Tribune reporter on board tried to reassure Illinois readers about the appearance of the corpse: Death had simply “softened and mellowed” the “strong outlines” of his face. But the Illinois delegates aboard the train, including Gov. Richard Oglesby, were taking no chances. Before leaving Albany, they had already cabled Springfield organizers, warning them to move up the funeral ceremony from May 6 to May 4.

Embalmer Charles Brown had said from the beginning that the corpse would eventually take on a mummified look, but he’d promised that for months it would look as “natural” as it did on the day of Lincoln’s death. Ten days of exposure to air and dust, and six days of jiggling on the train, had provoked a rapid erosion. More and more observers thought the president’s remains belonged in their burial place, not on display. With a week to go before the Springfield funeral, many citizens faced a dilemma: how to walk past the coffin to honor Lincoln while sensing that the display of his body amounted to disrespect.

Democratic editors had been handed a volatile story with which to whip Stanton. Unable any longer to attack their old nemesis Abraham Lincoln, they would soon turn their fire on his friend and collaborator, the secretary of war.

One daring Democratic editor, S.A. Medary—son of famous Copperhead journalist Samuel Medary, a perpetual thorn in the side of Unionists until his death in 1864—may have been the first writer in 1865 to turn the condition of the president’s corpse into an attack on Edwin Stanton’s management of the funeral. Peering into Lincoln’s coffin at the Columbus, Ohio, State House on Saturday, April 29—two weeks after the president’s death—the Columbus Crisis editor beheld “a dark, unnatural face whose features were plaintive and pinched and sharp, piteously like death.”

Lincoln himself, announced Medary, would have objected to “making a show of all that was mortal of a fellow-man.” By overruling Mary Lincoln “in her desire that the body of her husband should be entombed within a more appropriate period after death,” Stanton had desecrated his remains.

If anyone could have been counted on not to mind that his corpse was being exposed beyond all reasonable limits, it would probably have been Abraham Lincoln himself. He would have been reminded of some story (a feeding frenzy of farm animals at the trough?) that tweaked the millions of people who pressed forward to feast on his body. The champion of people’s access to their representatives might quite seriously have carried approachability to its logical conclusion: let the people have his body as long as they could stand having it.

This lengthy event made eminent republican sense. A repetitive national farewell—a vast coordination of military and civilian officialdom, and of elected officials at federal, state, and local levels—it celebrated Lincoln’s love for the people and their love for him. “Love is a rare attribute in the chief magistrate of a great people,” said P. D. Day, a Protestant preacher in Hollis, New Hampshire, in his address at the end of the funeral period. “We have so long regarded an iron will … as the first requisite for a ruler, that we have thought tenderness and love a weakness. But MR. LINCOLN has changed our views … he was beloved by the nation, and they loved him because he first loved them.”

Photo by Carol Highsmith. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Once the funeral train reached Illinois in May, the press lost interest in analyzing the condition of the corpse. The Chicago Tribune reverted to boilerplate reverence: “an extremely natural and life-like appearance, more as if calmly slumbering, than in the cold embrace of death.” The corpse hadn’t suddenly become lifelike again. The Tribune’s self-conscious diversion connoted that Lincoln was now finally resting among his Illinois intimates, those who could approach his body as if they were friends and family. The civic body had become the domestic body. The state of decay didn’t matter to those who cared. They could see only their beloved boy and man.

Excerpted from Lincoln’s Body: A Cultural History by Richard Wightman Fox. Copyright © 2015 by Richard Wightman Fox. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Co. Inc. All rights reserved.