Excerpted from How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City by Joan DeJean, out now from Bloomsbury USA.

The invention of Paris began with a bridge.

Today, people simply flash an image of the Eiffel Tower to evoke Paris instantly. It’s the monument that offers immediate proof that you are looking at the City of Light. In the 17th century, the Eiffel Tower’s role was played by a bridge: the Pont Neuf. The New Bridge was Henri IV’s initial idea for winning over the people of his freshly conquered capital city, and it managed that daunting task with brio. For the first time, the monument that defined a city was an innovative urban work rather than a cathedral or a palace. And Parisians rich and poor immediately adopted the Pont Neuf: They saw it as the symbol of their city and the most important place in town.

The construction of a new bridge over the Seine was initiated by Henri IV’s predecessor, the last king of the Valois dynasty, Henri III, who laid the first stone in May 1578. Some early projects conceived of a very different bridge, most notably, with shops and houses lining each side. In 1587, construction was just becoming visible above the water line when life in Paris was upended by religious violence. With the city in chaos, work on the bridge ceased for more than a decade.

In April 1598, Henri IV signed the Edict of Nantes: the Wars of Religion were officially over. A month earlier, the new king had already registered documents announcing his intention to complete the bridge. Henri III had offered no justification for the project; his successor, characteristically, laid out clear goals for it. He presented the bridge as a “convenience” for the inhabitants of Paris. He also characterized it as a necessary modernization of the city’s infrastructure—Paris’ most recent bridge, the Notre-Dame bridge, was by then badly outdated and far “too narrow,” as the king remarked, to deal with traffic over the Seine, which Henri IV described as rapidly expanding because new kinds of vehicles were now sharing the bridge with those who crossed on horseback and on foot. The new bridge would be financed in a previously untested manner: The king levied a tax on every cask of wine brought into Paris. Thus, as city historian Henri Sauval, writing in the 1660s, phrased it, “the rich and drunkards” paid for this urban work.

No prior bridge had had to deal with anything like the load the New Bridge was intended to bear—most significantly, a kind of weight that in 1600 was just becoming a serious consideration: vehicular transport. Earlier cities had only had to contend with transport that was relatively small and light: carts and wagons. In the final decades of the sixteenth century, personal carriages were just beginning to be seen in cities such as London and Paris. Nevertheless, with great foresight, each of Henri IV’s documents on the Pont Neuf adds new kinds of vehicles to the list of those to be accommodated. He was thus the first ruler to struggle with what would become a perennial concern for modern urban planning: the necessity of maintaining an infrastructure capable of handling an ever greater mass of vehicles.

The New Bridge became the first celebrity monument in the history of the modern city because it was so strikingly different from earlier bridges. It was built not of wood, but of stone; it was fireproof and meant to endure—it is now in fact the oldest bridge in Paris. The Pont Neuf was the first bridge to cross the Seine in a single span. It was, moreover, most unusually long—160 toises or nearly 1,000 feet—and most unusually wide—12 toises or nearly 75 feet—far wider than any known city street.

The bridge proved essential to the flow of traffic across Paris: Before, just getting to the Louvre from the Left Bank had been a famously tortuous endeavor that, for all those not wealthy enough to have a boat waiting to ferry them across, required the use of two bridges and a long walk on each side. The New Bridge also played a crucial role in the process by which the Right Bank became fully part of the city: In 1600, its only major attraction was the Louvre, whereas by the end of the century, the Right Bank showcased important residential architecture and urban works, from the Place Royale to the Champs-Élysées. In addition, whenever a major event transpired in seventeenth-century Paris, it either took place on the Pont Neuf or was first talked about on the Pont Neuf.

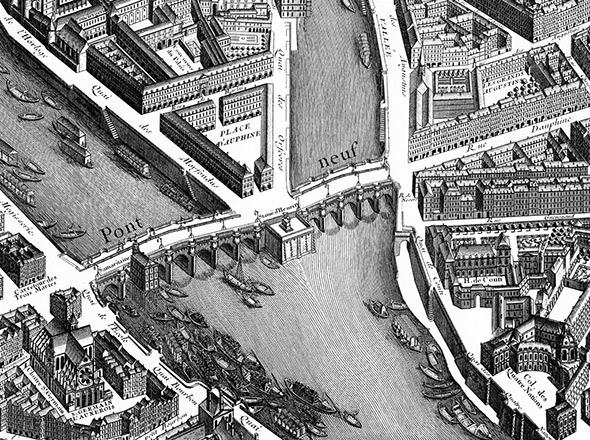

The 18th-century map above depicts the statue of Henri IV positioned in the middle of the bridge, the first public statue in the history of Paris. Parisians immediately turned the novel kind of monument into the most popular meeting place in the city. They created expressions such as “let’s meet by the Bronze King,” or “I’ll wait for you beneath the Bronze Horse.”

The enthusiasm with which Parisians welcomed the bridge helps explain why it became one of those rare public works that actually shape urban life. On the New Bridge, Parisians rich and poor came out of their houses and began to enjoy themselves in public again after decades of religious violence. The Pont Neuf became the first truly communal entertainment space in the city: Since access cost nothing, it was open to all. The greatest nobles disported themselves in ways amazingly unorthodox for a setting where anyone could see them. In February 1610, the 16-year-old Duc de Vendôme (Henri IV’s illegitimate son) was seen running around on the bridge engaged in a “heated battle with snowballs.”

And on the other end of the social spectrum, it was at the base of the Pont Neuf that public bathing in the Seine became popular, giving the least fortunate Parisians the chance to cool off from the summer heat. Soon after the bridge was opened, bathers and sunbathers began to congregate just below the bridge, in full view of all those crossing the Seine.

François Colletet’s periodical Le Journal (The Daily), reports that during the long hot summer of 1716, the police were obliged to step in when nude sunbathers were spotted, “on the riverbank by the Pont Neuf, where they were lying and walking about completely naked.” An order was issued “to forbid men from staying out on the sand by the Pont Neuf in the nude.” The Pont Neuf was a great social leveler.

The sidewalks on the Pont Neuf were the first the world had seen since Roman roads and something that had never been seen in a Western city. And no one knew what to call those who used these sidewalks. In official municipal documents, the people who walked there were called gens de pied, literally “people on foot,” a military term for foot soldiers. By the 1690s, French dictionaries included a new term, piéton, a pedestrian. Authors of guidebooks, aware that their readers would have had no previous experience with the phenomenon, explained, as Claude de Varennes did in 1639, that sidewalks were “absolutely reserved for pedestrians.” Pedestrians saw themselves for the first time as kings of the river.

The Pont Neuf was also built just when the use of vehicles of all kinds to get around in Paris was about to skyrocket. And because of the New Bridge’s size and its central location, a great many conveyances used it to cross the river. In no time at all, it thus became the poster child for what was quickly perceived to be one of the modern city’s greatest ills: the traffic jam.

An image from about 1700 is the original depiction of a traffic jam: it has a double title, “The Pont Neuf” and “l’embarras de Paris.” In the course of the 17th century and particularly in its final decades, that word, embarras, which until then had meant “embarrassment” or “confusion,” acquired a new meaning: “The encounter in a street of several things that block each other’s way.” A new kind of urban “confusion” had taken shape.

No one could have predicted how many activities would soon be vying for space on the bridge. To begin with, the Pont Neuf provided one of the original illustrations of the big city’s ever-accelerating appetite for news and of the rapidity with which technologies were invented to satisfy that craving. Rumors quickly spread through the crowd, giving rise to an expression: c’est connu comme le Pont Neuf—“everybody knows that already.” For the most part, however, news spread in far more organized ways.

The first French newspaper, Jean Richer’s Mercure françois, or “French Mercury,” began publication in 1611, well after the bridge had opened. It discussed a full year’s news at a time and appeared only several years after the events it described: The initial volume, for example, included coverage of 1604. To know what was going on in their city, Parisians relied on the Pont Neuf.

Engraved images of crucial people and events in the news were posted on the bridge. They were also available for sale in the shops that many printers set up either on or near the bridge. The same technique was used for printed news. Placards and posters of varying sizes were displayed prominently on walls throughout Paris, but nowhere more so than on the Pont Neuf. Contemporary accounts describe people reading aloud the posted news for those unable to read.

The existence of this informal newsroom on the bridge explains the way in which political sedition erupted in 1648, when violence returned to the streets of Paris for the first time since the 1590s. That August, civil war broke out after the arrest of a beloved member of the Parisian Parlement, Pierre Broussel. Broussel lived very near the bridge, as did the future author of one of the definitive accounts of the conflict, the Cardinal de Retz.

Retz was thus able to provide eyewitness testimony to the chain reaction set off “within fifteen minutes” of Broussel’s arrest at his home. The proximity of the Pont Neuf guaranteed that many Parisians were immediately informed of his arrest; they quickly formed an angry horde. The Royal Guard was on the bridge even as this was happening. The soldiers beat a retreat, but with a screaming mob on their heels. In no time at all, the crowd had grown to between 30,000 and 40,000. Retz described the “sudden and violent conflagration that spread from the Pont Neuf through the entire city. Absolutely everyone took up arms.” And later, when the opposition forces obtained Broussel’s release, observers noted “the cries of joy” that erupted from “the middle of the Pont Neuf.”

Until the first professional theaters opened their doors in the 1630s, the Pont Neuf was the center of the Parisian theatrical scene. Open-air performances contributed to the traffic gridlock, though not nearly so much as another kind of urban spectacle that also drew crowds to the bridge: shopping. As soon as the New Bridge was completed, a street market began. You could find trinkets, fashion accessories, and the most fetching bouquets in the city. Booksellers were the first to set up shop; there were soon at least 50 bookshops on the bridge.

Wealthy consumers being jostled about and distracted by everything from buskers to stray sheep must have seemed easy prey. Periodicals and guidebooks, memoirs and novels—all make an explicit association between the Pont Neuf and theft, especially clothing theft. The stories make it clear that, if you walked onto the Pont Neuf wearing your finest garments, you were in real danger of losing them before you reached the other side.

Despite all this, it’s clear that when Parisians got an expensive new outfit, they couldn’t resist showing it off by going for a stroll just where they knew it would be seen by the biggest crowd: on “the big stage of the Pont Neuf.” The Pont Neuf was expressly designed to encourage pedestrians to linger over the vista laid out before them. The bridge’s “viewing shelves” or “balconies” may have been the most remarkable of its innovations—they made Parisians aware that their city was now a sight worthy of visual appreciation.

Small wonder that the Pont Neuf became the first major modern tourist destination and that it inspired a true souvenir industry. The wealthiest travelers returned home with a painting of the New Bridge to hang in their salon or picture gallery, views that could remind them of the qualities of the Parisian experience that were to be found nowhere else. And for less prosperous visitors who wanted a reminder of Paris there was the equivalent of a souvenir trinket—fans that depicted daily life on Paris’ New Bridge.

Excerpted from How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City by Joan DeJean, out now from Bloomsbury USA.