Last summer in a used bookstore, I happened on an enormous, bound volume of Life magazine, from July–September 1945. I opened to the very first story in the first issue, July 2, 1945. The headline read:

“This Is Art by Piet Mondrian: Mondrian Hated Curves.”

Can you imagine a better headline for a story about an artist of squares and rectangles?

I was hooked.

I bought the volume, and some of the happiest and most confounding hours I’ve spent since have been leafing through it, trying to figure out how and why a 68-year-old weekly news magazine feels more exciting than almost anything I read today. The longer I spent with it, in fact, the more I wondered whether any magazine, ever, has been as interesting, and relevant, and fun, and durable as Life was during those three months.

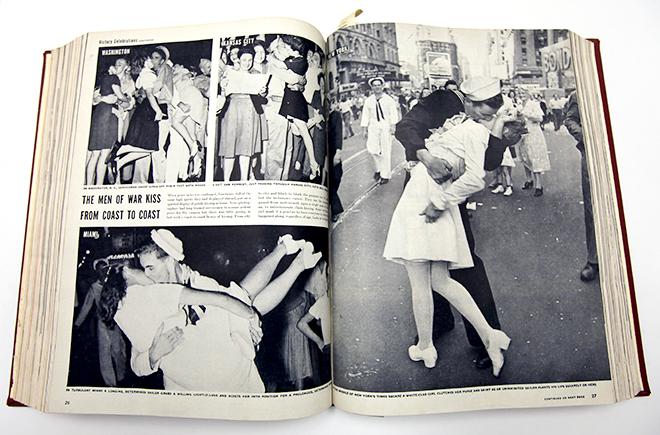

To understand why, I cataloged and classified the more than 200 stories and photo essays in the volume. For starters, these 13 issues include both the (arguably) most beloved magazine photo of the 20th century and the (arguably) most important magazine article of the 20th century. The Aug. 27 issue contains Alfred Eisenstaedt’s picture of a sailor kissing a nurse in Times Square after Japan’s surrender. (It’s the capstone of a spread of photos titled, “The Men of War Kiss From Coast to Coast.”) And the Sept. 10 issue gives 12 pages to Vannevar Bush’s “As We May Think,” the essay that predicted the information age, personal computers, the Internet, networking, and the democratization of knowledge. Bush’s essay had originally run in the Atlantic three months earlier, but the editors of Life, recognizing its profound importance, republished it, and gave it the huge audience that helped make it legend.

Photo by Slate, Life Magazine © Time Inc.

It would have been hard for anyone to make a boring magazine in summer 1945, given that these were perhaps the three most eventful months in human history: the end of World War II and the surrender of Japan, the dropping of the atomic bomb, the signing of the U.N. charter, the discovery and initial prosecution of Germany’s holocaust crimes. Life’s writers and photographers captured an astonishing amount of that history. (Life was the third great magazine of Henry Luce’s empire. Time summarized the world through aggregation, 75 years before aggregation was invented, and Fortune put American business under a microscope. The purpose of Life was: The world in pictures.)

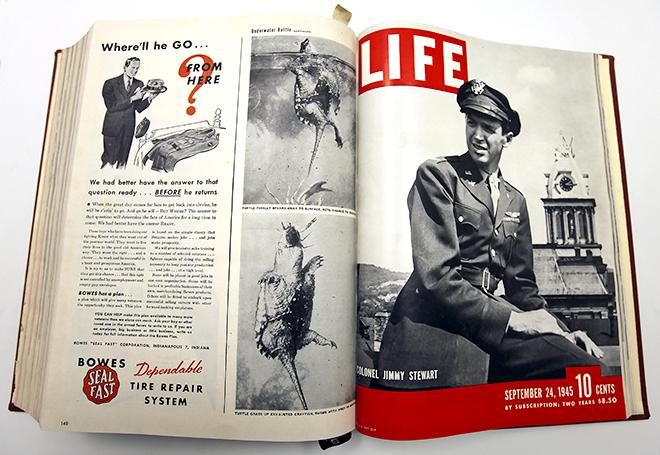

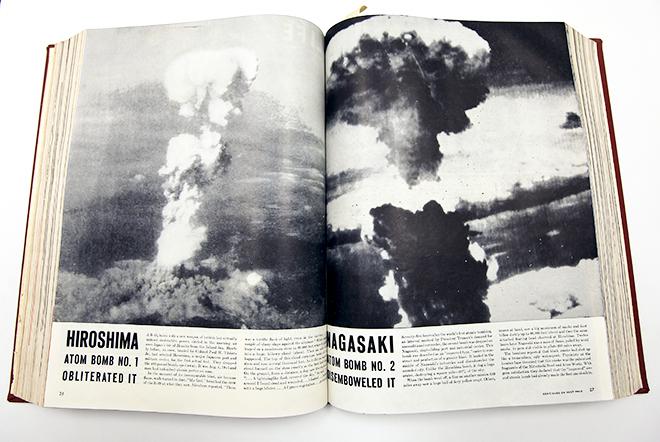

Life ran the aerial photos of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs that you still remember. It visited Hitler’s bunker just after Hitler’s suicide, and Mussolini’s love nest. It traveled home with Audie Murphy, the war’s most decorated soldier, and photographed him with his sweetheart, and also with actor and Col. Jimmy Stewart, perhaps the single most famous American in uniform. Life was there for the start of the Nuremberg tribunals, the trial of Norwegian Nazi collaborator Vidkun Quisling, and the botched suicide attempt of Japanese military leader Hideki Tojo. It took the United Nations charter so seriously that it published photos of every single one of its signatories at the moment he signed the document—a grid of 50. It went on vacation with new President Harry Truman, and rode down the avenues of lower Manhattan with conquering Gen. Dwight Eisenhower at his tickertape parade. Oh, and it also toured the eugenic compound that had housed children of German SS officers, bred to be Aryan superbabies. Life was there.

Photo by Slate, Life Magazine © Time Inc.

But it’s not just that it was there. The magazine also understood—and defined—the themes would preoccupy the America to come. It speculated about post-war nuclear strategy just days after Hiroshima. The magazine was prescient about issues of terror. John Hersey wrote about Japanese kamikazes, a searing essay about suicidal terrorism that feels alarmingly current. A photo essay chronicled the “military commissions” using new and untested principles of law to prosecute German war criminals and collaborators—a preview of the very fight we’ve been having over Gitmo’s commissions. A photo essay chronicles the crash of a fog-bound B-25 bomber into the Empire State Building, an event that would be recalled on 9/11.

Photo by Slate, Life Magazine © Time Inc.

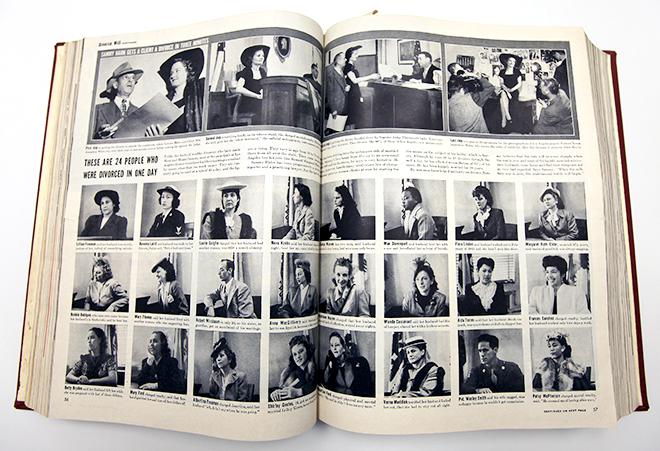

Life sought to prepare its readers for post-war society. There’s a sublime photo essay about divorce, with portraits of 22 women (and two men) who got unhitched in Los Angeles on a single day.* The magazine profiled a little-known regional department store, Neiman-Marcus, with the prediction that its brash Texas style could make it a national name. Life was infatuated with American science and engineering, and made the case that the ingenuity that was winning the war would win the future. Every issue explained—with models, illustrations, and high-speed photography—a scientific breakthrough that would shape the post-war world: radar, napalm, air conditioning, nuclear fission, Plexiglas …

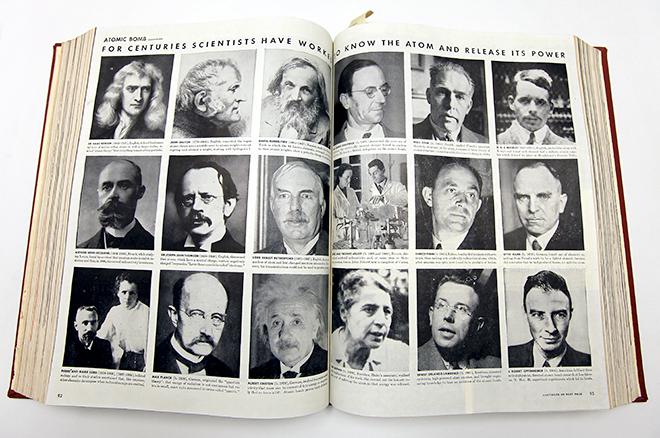

The magazine’s eye for culture was sharp. In addition to Mondrian, Life profiled artists Max Weber and Salvador Dali. The magazine serialized Names on the Land, a peculiar book about American place names that would become a cult classic. One tart criticism of Henry Luce’s magazines was that “Time is for people who can’t think, and Life is for people who can’t read or think.” But to my 2013 self, the 1945 Life respects subtlety and intelligence of readers more than modern magazines. Consider that Mondrian story: Can you imagine the most popular American magazine of 2013 devoting its first half-dozen pages to a dead, difficult, abstract artist? Life ran an achingly long tribute to John Maynard Keynes, the world’s most influential economist. A hefty essay speculated on whether the University of Chicago’s great books curriculum should become the model for American higher education. One issue gave six full pages to the history and purpose of the American secretary of state, with huge portraits of a dozen of them. In another issue, you find brief bios of 20 scientists who created nuclear age, from Isaac Newton to J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Photo by Slate, Life Magazine © Time Inc.

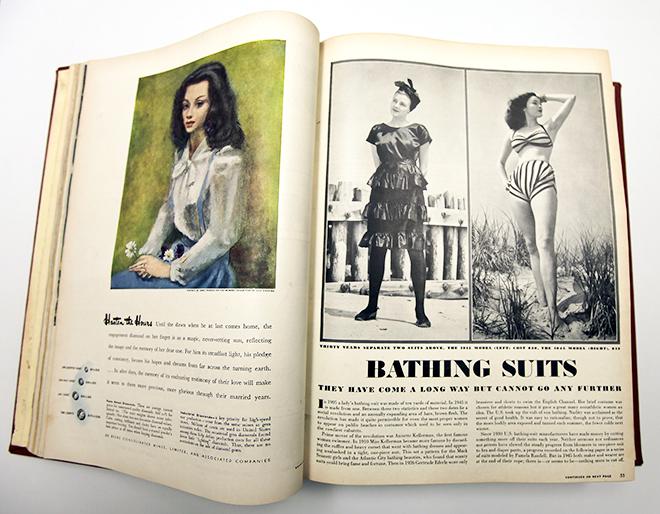

Does any of 1945 Life feel ridiculous, wrong, or dated? Yes, but surprisingly little. The Hollywood coverage celebrates long-forgotten movies and starlets who never became stars. (Betty Hutton? Peggy Ann Garner?) It’s conservative about fashion: One hilarious photo essay on skimpy bathing suits insists they “cannot go any further,” even as it depicts models wearing two-piece suits that a grandmother would feel modest in today. And northwest Ohio must wince at this feature: “Toledo: Scale model gives citizens a prophetic look at the wonderful city they could have in 50 years.” Not so prophetic. The bigger misstep in Life is what’s not there: hardly a word about segregation or poverty.

Photo by Slate, Life Magazine © Time Inc.

No contemporary magazine could duplicate Life’s success, and not just because 1945 was such a monumental year. No modern magazine has remotely close to its influence. The most popular magazine in America, Life circulated 4 million copies a week, and was read by 13.5 million people—10 percent of the population. The largest weekly magazine now, People, has a smaller circulation than Life even though the U.S. population is 2.5 times as large as it was then. And in an age before TV, Life’s photographs were a dominant way that Americans saw the world.

Life could speak to a shared idea of America. As importantly, it wanted to speak to a shared idea of American progress. As Alan Brinkley explains in The Publisher: Henry Luce and His American Century, Luce sought to use Life and Time to outline and enforce a vision of what America should be: optimistic, scientific, inclusive, forward moving. To modern eyes, such confident optimism is unfamiliar, but appealing. Such certainty and such confidence in shared values don’t—and couldn’t, and probably shouldn’t—exist modern journalism.

But Life could depend on having readers who were ready to listen to this vision of America. Fresh off their triumph in the war, their political ideals vindicated, their science and engineering proven the best in the world, Americans were happy to be flattered by Life’s positive, optimistic vision of post-war society. The magazine could get away with a universal we that no magazine would dare today. (This is not to say we has vanished from journalism. But what persists is an ideological we, a we of the left or right that’s opposed to a wrong-thinking them—not a we that includes all Americans.) The story Life was telling about America wasn’t a true story—midcentury America without racial conflict is a fantasy—but it was truish, and it was a story that many Americans wanted to hear.

Perhaps the most remarkable feature from the summer of 1945 was a 10-page spread about American folk songs. Overlaid on full-page photographs of appropriate American icons—a church, a steam engine—are the lyrics to folk songs: “Home on the Range,” “O Susanna,” “America the Beautiful,” and others. It’s sappy, and powerful, and not cynical at all. And every time I look at it, I sing.

Correction, Jan. 3, 2014: This article originally misstated how many women and men were photographed in a Life spread about divorce in Los Angeles. There were 22 women and two men, not 23 women and one man. (Return.)