This is an excerpt from Rich Cohen’s The Fish That Ate the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King, out this week from FSG.

Samuel Zemurray took his money and went south. Wisteria bloomed along the railroad tracks. Towns drifted by. He could smell the ocean before he could see it. He was like a kid on the frontier, who, a day after the harvest, folds his savings into a roll and goes to try his luck in town.

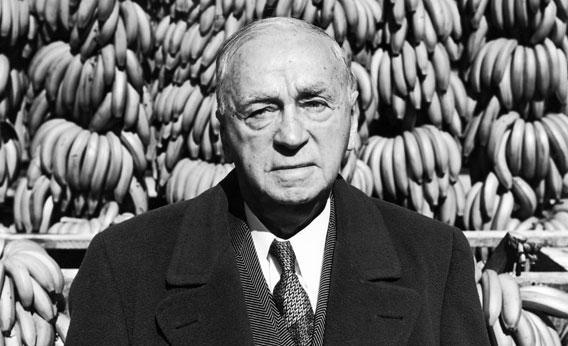

He was 17, a big kid, 6-foot-3 in boots, the wingspan of a condor. It was said he could swear in five languages. Having emigrated from Russia in 1891, Sam settled in Selma, Ala., where his uncle owned a store. That’s where he saw his first banana: golden-green, piled in the wares of a vagabond peddler. Soon after, charmed by this hint of paradise, he headed to the Gulf, looking for his own supply. It was the beginning of an adventure that would eventually make Sam one of the most powerful men in America, the head of the United Fruit Company, “El Pulpo,” the dreaded octopus with its tentacles in everything. In later years, Sam could alter the history of South America with a phone call, a string of expletives, a wave of the hand. But in the beginning, he was just a kid with a realization about bananas—an epiphany that changed everything.

Mobile was booming in the last years of the 19th century, a seedy industrial port filled with all the familiar types: the sharpie, the financier, the scoundrel, the chucklehead, the sport. Sam was a bit of everything. He could be shrewd, but he could also be naive. He was greedy for information. He took a room in a seamen’s hotel near the port. The waterfront was crossed by train tracks—dozens of lines converged here. Boxcars crammed with coal, fruit, cotton, and cane stood on the sidings. The railroad conductors were the aristocrats of the scene. They drank coffee in the station house, smug in their checkered caps. The docks were crowded with stevedores, most of them immigrants from Sicily. The train sheds were crowded with peddlers, mostly Jewish immigrants from Poland and Russia. They bought merchandise off the decks of ships and sold it from carts in the streets of Mobile.

One evening, Sam stood on the wharf watching a Boston Fruit banana boat sail into the harbor. The Boston Fruit Company, which would become United Fruit, dominated the trade, with a fleet that carried bananas from Jamaica to Boston, Charleston, New Orleans, and Mobile. Zemurray would have seen one of the smaller ships that made the trip to the Gulf ports, a cutter with sails and engine. The funnel sent up black smoke. The pier strained under the weight of unloaders who appeared, as if out of nowhere, whenever a ship landed. As soon as the boat was anchored, these men swarmed across the deck, ants on a sugar pile, working in organized teams.

In the South, in the days before mechanical equipment, bananas were unloaded by hand, the workers carrying the cargo a stem at a time—from the hold, where the shipment was packed in ice, onto the deck of the ship. A banana stem is the fruit of an entire tree—100 pounds or more. Each stem holds perhaps 100 bunches; each bunch holds perhaps nine hands; each hand holds perhaps fifteen fingers—a finger being a single banana.

Sam would have watched closely as the workers formed lines that snaked from the deck of the ship down a ramp, and across the pier to the waiting boxcars. Each stem was passed from man to man until it reached the open door of the train, where an agent from the company examined it for bruises, freckles, color. If the stem passed muster, it was loaded into the car, which was air-cooled and straw-filled. When the car was full, the door was swung shut and locked. An empty car was rolled into its place. This continued for hours—a shift might run from 3 p.m. until midnight. When a train was packed, the switchman signaled and the cargo was carried across the South.

The bananas that did not past muster were dumped on the side of the yard, where they were further divided. Some were designated as turnings, meaning they were on their way to being worthless. At the end of the day, they were sold at a discount to local store owners and peddlers. You could see them, with their carts piled high, trundling through the streets, calling, “Bananas, bananas for sale! A nickel a bunch! Yes, we have bananas, we have bananas for sale!”

The bananas that did not make the cut as greens or turnings were designated “ripes” and heaped in a sad pile. A ripe is a banana left in the sun, as freckled as a Hardy boy. These bananas, though still good to eat, delicious even, would never make it to the market in time. In less than a week, they would begin to soften and stink. As far as the merchants were concerned, they were trash.

Sam noticed everything—the care with which the bananas were handled, the way each boxcar was filled and rolled to a siding, how men from the banana company, college men, moved through the crowd barking orders—but paid special attention to the growing pile of ripes. Anything can cause a banana to ripen early. If you squeeze a green banana it will turn in days instead of weeks; ditto if it’s nicked, dented, or banged. A ripe banana will cause those around it to ripen, and those will cause still others to ripen, until an entire boxcar is ruined. Before refrigeration was perfected, as much as 15 percent of an average cargo ended up in the ripe pile.

Sam grew fixated on ripes, recognizing a product where others saw only trash. He was the son of a Russian farmer, for whom food had once been scarce enough to make even a freckled banana seem precious.

Photograph by Rich Cohen.

After the ship had been unloaded, after the trains had carried off the green bananas, after the merchants and peddlers had taken away the turnings, Sam walked down to the pier to talk to the company agent. They spoke as the sun went down, the man with the Ivy League elocution and the kid with the Russian accent, who rolled his Rs and spit his vowels. Zemurray had $150. That was his stake. He figured it would go further if he spent it on ripes. He was no fool. He knew what this meant—that he would have to move fast, that he was entering a race with the clock. Three days, five at the most. After that, he would be left with a pile of glue. But he believed he could make it. As far as he was concerned, ripes were considered trash only because Boston Fruit and similar firms were too slow-footed to cover ground. It was a calculation based on arrogance. I can be fast where others have been slow. I can hustle where others are satisfied with the easy pickings of the trade.

Zemurray’s first cargo consisted of a few thousand bananas. He did not spend all his money but retained a small balance, which he used to rent part of a boxcar on the Illinois Central. The trip to Selma was scheduled to take three days, meaning he would have just enough time to get the fruit to market before the sun did its worst. In most cases, a fruit hauler would spend a few dollars extra for a bed in the caboose, but since the freight charge used the last of his money, Zemurray traveled in the boxcar with his bananas, the door open, the country drifting by.

The train left on a Tuesday morning, say, the sun fiery above the smoky freight yard dawn, the clank of wheels over switches, the ocean drifting away. Color and country: blue in the morning, green at midday, red in the evening. Zemurray sat in the boxcar doorway. The train traveled maddeningly, infuriatingly, exceedingly slow. In the country, it went the speed of a trotting mule. In the towns, it was no faster than a man walking. In the cities, it stopped altogether, sometimes for hours, waiting for cargo and crew. Zemurray paced the railroad bed, hands on his hips, muttering.

Stop lights. Temporary holds. What was supposed to be three days was turning into five, six. With each hour, the bananas became more pungent. He spoke to the conductor, who commiserated, saying, “What a terrible shame.”

In a Mississippi train yard, where the redbrick buildings, feed stores and tinsmiths crowded close to the tracks, a brakeman, hearing Sam’s story, said, “You’ve got good product there. If you could just get word ahead to the towns along the line, I’m sure the grocery owners would meet you at the platforms and buy the bananas right off the boxcars.”

During the next delay, Zemurray went into a Western Union office and spoke to a telegraph operator. Having no money, Sam offered a deal: If the man radioed every operator ahead, asking each of them to spread the word to local merchants—dirt cheap bananas coming through for merchants and peddlers—Sam would share a percentage of his sales. When the Illinois Central arrived in the next town, the customers were waiting. Zemurray talked terms through the boxcar door, a tower of ripes at his back. Ten for eight. Thirteen for ten. He broke off a bunch, handed it over, put the money in his pocket. The whistle blew, the train rolled on. He sold the last banana in Selma, then went home in the dark. When he tallied his money, it came to $190. His first real success: After accounting for expenses, Sam had earned $40 in six days.

Zemurray had stumbled on a niche: ripes, overlooked at the bottom of the trade. It was logistics. Could he move the product faster than the product was ruined by time? This work was nothing but stress, the margins ridiculously small (like counterfeiting dollar bills), but it was a way in. Whereas the big fruit companies monopolized the upper precincts of the industry—you needed capital, railroads, and ships to operate in greens—the world of ripes was wide open. Within a few weeks of his return to Selma, Zemurray set out again, then again, then again. It was in these months, on train platforms and in small towns, that Zemurray first came to be known as Sam the Banana man.

Historians later described the young Zemurray as a fruit peddler, no different from other poor Jews who pushed carts through Manhattan’s Lower East Side, except instead of a wagon, Sam worked out of a boxcar. (He was “Sam the Banana Man,” according to Life, “who once used railroads as pushcarts.”) It made sense, but only in a shallow way. In truth, Sam Zemurray was more interesting and unique—as a salesman of a perishable product, he was a kind of existentialist, skirting the line between wealth and oblivion, health and rot, a rider of railroads, a chaser of time. It was life: Move the fruit now or you’re ruined forever. He became a gambler by necessity—a risk-taker, a salesman, a brawler. “The little fellow,” as the big wheels in Boston called him, but the little fellow would build a kingdom from ripes.

Sam eventually went into turnings, yellows, even greens. By 1912, he was living in the jungle in Honduras, where, working with mercenaries, banana cowboys, he had overthrown the government, empowering a president more friendly to Cuyamel, the company Sam led to victory against United Fruit. In the end, he would live in the grandest house in New Orleans, the mansion on St. Charles that is now the official residence of the Tulane president. He continued to wield tremendous influence into the mid-’50s, a powerful old man who threatened, cajoled, explained, a mysterious Citizen Kane-like figure to people in his city. When he died in 1961, the New York Times called him, “The Fish That Swallowed the Whale.” But part of him would always remain that big kid peddling ripes from a boxcar on the Illinois Central.