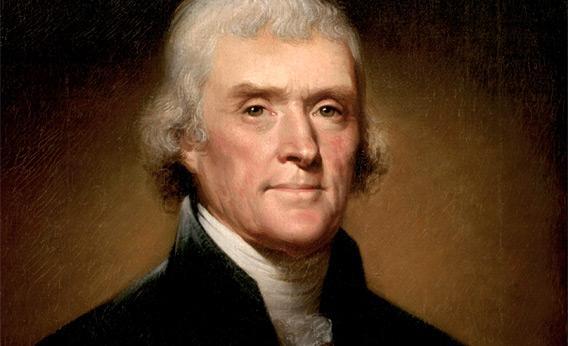

Thomas Jefferson wrote that “music is the favorite passion of my soul.” He was an avid collector of musical scores, and believed that the new republic needed to build a musical tradition. The blog “Musicology for Everyone” lists the third president as the second most musical, after Warren Harding, who played the sousaphone well enough to join the band celebrating his election.

Despite Jefferson’s ear for music, however, little attention has been paid to what he heard and how he processed those sounds. A modern-day visitor to Charlottesville, Va. and Jefferson’s estate, Monticello, has a pretty good idea of what Jefferson’s hometown looked like 200 years ago—but what did it sound like? The modern soundscape has car alarms, construction rumble, and amplified music. The sounds of cicadas, thunder, speech, bells, and horse hooves animated early America. Music resounded in taverns, parlors, political rallies, official celebrations, and dances.

Thanks to new exhibits at Monticello and at the Smithsonian Museum of American History, we can get an idea of what life was like not just inside the white columned residence of the third president but also on Mulberry Row, in the homes of slaves who made Jefferson’s life possible. The exhibits display the fundamental Jeffersonian paradox: a man who was a champion of liberty and a slaveholder. It’s a paradox Jefferson himself seems not to have wanted to be reminded of.

Blocking unwanted sounds is easy in our iPod era. Headphones allow us to avoid crying babies, chattering passengers, and other unpleasant noise. Jefferson didn’t have such technology, but he found other ways to mute the sounds of his plantation at work. For starters, Jefferson kept “noise” outside the house. My colleague Craig Barton notes that Jefferson used architecture and landscaping to “render invisible the slaves and their place of work from the important symbolic view of the property.” Placing the slave quarters and workspaces downslope also minimized slave sounds penetrating Mr. Jefferson’s bastion—sound travels poorly uphill. What noise did arrive at Jefferson’s home was kept at bay by plate glass windows.

Outside those windows, and down the hill, Monticello reverberated with sounds of discipline and work. In the nailery, from dawn to dusk, 12 boys stood around open fires heading nails with heavy hammers. Occasionally, the overseer would beat them. All of these sounds, metal on metal and whip on flesh, punctuated the workshop even as they remained inaudible in the planation house.

In Jefferson’s day, even black music was understood as noise. Frederick Douglass’ call to listen to the meanings of slaves singing and abolitionists’ collections of slave songs were still decades away. We know Jefferson heard slaves make music, and yet he mentioned their ability to sing or play an instrument only twice in all of his writings. Their songs simply did not count as the elevated art that was the president’s favorite passion.

As for the music he did listen to, Jefferson probably heard and hummed much more than he played—his impressive skill as a fiddler is likely a myth. As his granddaughter explained, “Mr. Jefferson never accomplished more than a gentlemanly proficiency.” The violin music in his collection is nearly untouched (in contrast to the keyboard music that belonged to his wife and daughters), and he last purchased fiddle strings in 1793, before he bought much of his music.

Contrary to received notions of Jefferson the prude, some of the music in his collection feature lyrics that might make a UVA frat boy blush:

When first I saw Betty and made my complaint

I whined like a fool and she sighed like a Saint.

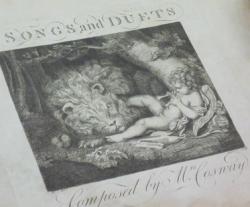

Maria Cosway, the composer, musician, and artist with whom Jefferson had a romance, sent him a set of her songs whose cover depicts a cupid and a lion engaged in interspecific activities that violate several state laws in the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Courtesy Bonnie Gordon.

Jefferson needed scores, because in his day if you wanted music you had to make it. The part of the family music collection not lost in various fires and Jefferson’s catalog of his complete collection is all we have left of his parlor playlist, which would have been played mostly by his daughters and granddaughters. The collection reveals the music he heard, wanted to hear, or wanted others to think he heard.

Among other things, it contains music for Spanish guitar, French harpsichord sonatas, arrangements of popular Scottish ballads for various instruments, and old editions of ballad operas from London pleasure gardens. It also has manuscript music notebooks that his wife and in-laws kept. His wife, Martha Wayles Jefferson, copied keyboard exercises, popular songs, and other short pieces.

Jefferson amassed his collection through his travels and from his emissaries. Writing in 1778 to Giovanni Fabbroni, an Italian naturalist and economist, he declared that “fortune has cast my lot in a country where [music] is in a state of deplorable barbarism.” Jefferson hoped to create a sonic past and present for the new country. He understood the ways sound could be mobilized for political purposes; for him, music collecting was also nation-building. Jefferson kept scrapbooks during his presidency, in which he collected hundreds of songs linking national song and national identity. The newspaper clippings do not have notation but they do mention the tunes to which the lyrics are to be sung. Odes to liberty, celebrations of July Fourth, and odes to Jefferson himself are sung to “Yankee Doodle Dandy” and “Anacreon in Heaven” (the tune for “The Star Spangled Banner”). These songs were performed for specific political events, with the lyrics tailored to patriotic purposes. Try this version of “Anacreon in Heaven,” “written for the Anniversary of American Independence”:

Well met, fellow freemen!

Let’s cheerfully greet,

The return of this day, with a

Copious libation.

For freedom this day in her chosen retreat,

Hailed her favourite JEFFERSON

Chief of our nation.

A chief in whose mind

Republicans find,

Wisdom, probity, honor and

Firmness combined.

Let our wine sparkle high, whilst

We gratefully give,

The health of our Sachem, and

Long may he live.

Speaking of sachems, though Jefferson seems to have had little affection for black music, he championed the music of Native Americans, using them to counter European claims about the inherent degeneracy of the New World. But Jefferson also sought to create an American national music by appropriating Scottish and Irish folk songs. In 1838, his spunky granddaughter Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge wrote in her travel diary that “The music of Scotland may almost be called the national music of Virginia. The simple, plaintive or sprightly airs which every body knows and every body sings are Scotch. … This music is natural, intelligible, comes home to every body’s business and bosom.”

American also borrowed from the Scotch and Irish the fiddle tune. Though Jefferson himself didn’t do much fiddling at Monticello, others did. Isaac Jefferson Granger, one of his slaves, said that Randolph Jefferson, Thomas’ little brother, “used to come out among the black people, play the fiddle and dance half the night.” The sons of Sally Hemings played frequently when Jefferson’s daughters and granddaughters wanted dance music. According to Jefferson’s granddaughter, “On Saturday next the youngsters of Monticello intend to adjourn to the South-Pavilion and dance after Beverley [Hemings’] music.”

And yet Mr. Jefferson mentions none of these sounds in his writings. This studied deafness cannot be disconnected from his scientific racism. Jefferson’s two mentions of African American music-making come in the laws section of Notes on the State of Virginia, in which he explains the racial inferiority of blacks as a way of excluding them from citizenship. He writes that blacks “are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.” Of their music making, he says, “they are more generally gifted than the whites with accurate ears for tune and time, and they have been found capable of imagining a small catch. … Whether they will be equal to the composition of a more extensive run of melody, or of complicated harmony, is yet to be proved.” Blacks, in other words, could play music but not compose it. Denying blacks a musical voice was part of a larger project of dehumanization. He insisted that blacks, in contrast to Europeans, were incapable of creativity, thoughtfulness, and originality. This in turn led him to render blacks incapable of citizenship, which he believed depended, among other things, on reason and aesthetics.

Despite his best efforts, however, Jefferson couldn’t completely ignore the sound of Mulberry Row. His daughters sang corn-shucking and rowing songs that they learned from the slave women who raised them. In Jefferson’s writings, black music-makers were no more a part of the music traditions he valued than they were of the national family he created. But they nonetheless participated in making Virginian music. Accounts of white women dancing to black fiddlers and sometimes dancing with them remind us that even for Mr. Jefferson the musical boundaries he wanted to police were as fluid as the sexual boundaries between black and white, as he well knew. The rhetoric and the practice create a dissonance it’s hard to imagine Jefferson’s keen ear not hearing.