Fifty years ago this spring, the great literary critic Edmund Wilson, author of classic intellectual histories of Marxism, French symbolism, English literature of all kinds, and many other subjects, published one of the most important and confounding books ever written on the American Civil War. Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War both offended and inspired its many reviewers and readers in 1962, when America was celebrating the Civil War Centennial, and it is still likely to dismay as well as enlighten the serious-minded student of the central event of American history. A mythic and sentimental Civil War is still abroad in our culture; reading Wilson anew during these sesquicentennial years will puncture those myths as it explains why they persist. Before or after 1962, no one ever wrote a book quite like Patriotic Gore and it deserves a rereading in our own wartime.

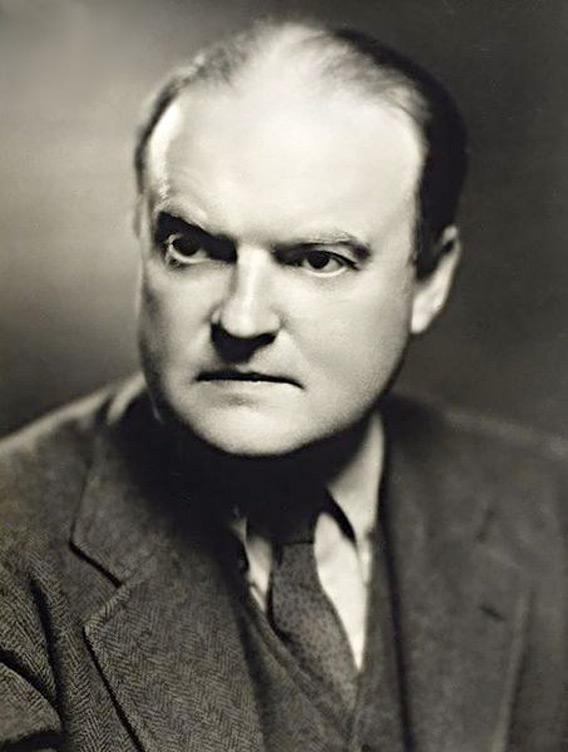

Wilson was an intimidating, irresistible writer. Experts in English departments can argue the point, but he was the preeminent American literary critic/historian of the 20th century. Born in Red Bank, N.J. in 1895, the son of a stalwart Republican father who was a successful lawyer and an occasionally institutionalized depressive, and a deeply caring mother who wished he would be more athletic, Wilson went to boarding school, where he cultivated a love of literature, and then to Princeton, where he graduated in 1916. When the United States entered the Great War, he enlisted in the Army’s ambulance corps, spending much of 1918 working in a hospital complex in Northeastern France. That experience behind the lines of the Western Front, but immersed in its horrible results—his jobs were burying the dead, attending to gas victims, and preventing suicides on the mental ward—shaped Wilson’s moral view of war for the rest of his life. He openly opposed World War II, and by 1960 had become so fiercely pacifist and so discouraged with the Cold War and its proliferation of nuclear weapons that he refused to pay his taxes.

From the 1920s through the 1940s, Wilson wrote prolifically in nearly every genre, including fiction, social criticism and the nonfiction essay, autobiography, and especially literary history. Almost no part of world literature remained beyond his interest. Wilson would chart a plan of superhuman reading and research, spend years in the literary mines of his own imagination, and then produce classics such as Axel’s Castle (1931), a study of French symbolism and modernism, and To the Finland Station (1940), his massive intellectual history of ideas of social justice from the French Revolution to the Russian Revolution of 1917, as well as a brilliant series of portraits of writers and suffering artists (especially Karl Marx) trying to change the world with their pens. To grasp the structure and purpose of Patriotic Gore, one should first read Wilson’s Finland Station. There we see him endlessly pursuing the meaning of the actor in history, and above all, the question the nature, trajectory, and meaning of History itself.

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, Wilson began to systematically read fiction, memoirs, and speeches of the Civil War generation. “I have been reading up the literature of the Civil War—some of which is wonderful,” Wilson wrote to his friend John Dos Passos in 1952. Some of his discoveries should be “classics,” he complained, but suffered obscurity because “the Civil War has to some extent been a taboo subject.” Southerners, he maintained, refused to read “Northern books,” and too many Northerners sought to “forget the whole thing.” He sent Dos Passos a list of books he thought should be required in schools and colleges. A year later, he wrote to another friend: “It was not a period when belles-lettres particularly flourished. … But I don’t know of any other historical crisis in which everybody was so articulate.”

In the ’50s Wilson wrote to many friends about his sudden amazement at finding so many good Southern writers and military memoirists on both sides. “My greatest surprise has been Sherman’s book,” he wrote, “I had had no idea that he was such an interesting character—rather complex, even a little unbalanced.” When Patriotic Gore finally appeared in 1962, it was this element of sheer surprise for so many reviewers and readers that gave the book its unique place in the Civil War Centennial period.

***

Patriotic Gore is really two books in one, and it has always been read and criticized that way. The first is the Introduction, a mesmerizing if troubling manifesto, which Wilson wrote at the very end of the process in 1961, and in the midst of various Cold War crises in the world. The second consists of 26 chapters, analyzing the works and illuminating the lives of approximately 30of the writers Wilson had discovered. The book endures because it is an unprecedented, and as yet unmatched, literary history, and because of its often sparkling, if controversial, personal judgments, both historical and aesthetic.

Wilson’s Introduction has been called everything from shocking to naive to brilliant; some considered it unpatriotic, even un-American. Wilson delivered a blunt and sustained critique of the Cold War and of war itself. In the postscript for a book of collected essays from the ’20s and ’30s, The American Earthquake (1957), Wilson explained his opposition to American involvement in World War II, and rehearsed for his performance in Patriotic Gore. He suggested the moral equivalence of Nazi mass murder and American carpet-bombing of cities and the use of atomic weapons to kill civilians. “The Nazis smothered people in gas-ovens,” Wilson wrote without hesitation, “but we burned them alive with flame-throwers and, bomb for bomb, we did worse than the Nazis. …” One can imagine how this was received in Eisenhower’s America of 1957, in the wake of McCarthyism and in the midst of Cold War fear of nuclear attack.

In every nation Wilson had come to see the same impulse: “the irresistible instinct of power to expand itself, of well-organized human aggregations to absorb or impose themselves on other groups.” The same “sub-rational reason” lay at the root of both the conquest “of the South by the North in the Civil War, of Germany by the allies.” With this degree of cynicism, one wonders how Wilson managed to find brilliance, humor, and even the sublime in so many Civil War writers.

As Wilson finished Patriotic Gore he was very discouraged by the Cold War, by nuclear testing, and U.S.-Soviet saber-rattling. In the summer of 1961 he unloaded on Alfred Kazin: “the U.S.A. is getting me down … I don’t see how you still manage to believe in American ideals and all that.” Wilson seems never to have gotten over his experience of 1918-19 in those French hospitals.

The alienation Wilson felt from what he called the “United States of Hiroshima” produced a belligerent, blasphemous screed against his country’s sense of history, and especially its foreign policy. Some of his historical judgments and moral equivalences can still seem disturbing today. But it is not merely a perverse diatribe full of prickly opinions; at times it is a weirdly brilliant exposition of “anti-war morality.”

Wilson scorches all forms of nationalistic pieties, all excuses for mobilizing societies for violence, all manipulations of history to justify conquest. Recalling a Walt Disney nature film in which a sea slug devours smaller sea slugs by natural instinct, he urged a “biological and zoological” approach to the human obsession with war. We should ignore the “war aims” pronounced by nations, he suggested, and understand that the “difference … between man and other forms of life” is that man has invented what he calls “morality’ and ‘reason’ to justify what he is doing. …” “Songs about glory and God, the speeches about national ideals,” insisted Wilson, are only the “self-assertive sounds which he [man] utters when he is fighting and swallowing others.”

A direct condemnation of humankind’s “war-like cant” could hardly have been more provocatively fashioned than in Wilson’s infamous “sea slug” metaphor. He spared no one in the withering assault, not the French in their revolution nor the Russians in theirs. He judged Americans, if anything, the worst offenders: They were “self-congratulatory grandchildren of a successful revolution” whose “appetite” must be fed by ever more self-aggrandizing slogans such as the “American Dream, the American way of life, and the defense of the Free World. …” Wilson rejected virtually all ideological reasons for war.

Most of all, Wilson wanted Americans to admit that historically, they had been “devourers” too, experts at fashioning mythic reasons for collective violence. He surveyed America’s ever-replenishing theory of manifest destiny, in which he included the North’s “repression of the Southern states when they attempted to secede from the Union. …” Indeed, he offered an explanation of the coming of the Civil War borrowed almost completely from the Lost Cause tradition, accented with his own brand of biological determinism. Northerners’ concern to preserve the Union, he maintained, had nothing to do with freeing slaves. When the “militant North” (meaning abolitionists) made a “rabble-rousing moral issue” out of slavery, it provided what all wars need— “myth” and “melodrama” for which men are willing to die. In language no diehard Lost Cause advocate of the turn of the 20th century nor neo-Confederate of the early 21st could improve upon, Wilson said Lincoln’s government sought to “crush the South not by reason of the righteousness of its cause but on account of the superior equipment which it was able to mobilize and its superior capacity for organization.” Wilson is one of those rare writers who can be at once profoundly wrong and equally interesting.

Although his views were rooted in some old mainstream histories still popular in the 1950s, Wilson’s apparent Southern sympathies seemed jarring to some readers. Given Wilson’s radical proclivities, one might think he would have read W. E. B. Du Bois on Reconstruction, or at least have encountered John Hope Franklin on the whole of black history or Kenneth Stampp on slavery in his voracious reading. But no such evidence emerges in the book. On the contrary, he all but cast a vote for “white Southerners” of the early 1960s, “rebelling against the federal government, which they have never forgiven for laying waste their country, for reducing them to abject defeat and for the needling and meddling of the Reconstruction.” As he pushes on in defense of the poor benighted South, his language sounds badly out of tune with historical interpretations of today and very much in tune with 21st-century white political resentment. “When the federal government sends troops to escort Negro children to white schools and to avert the mob action of whites, the Southerners remember the burning of Atlanta, the wrecking by Northern troops of Southern homes, the disfranchisement of the governing classes and the premature enfranchisement of the Negroes.” As a tax-resister against the Cold War, Wilson invented historical soul mates out of Southern secessionists who had risked all in the name of a slaveholding republic.

Why, for Wilson, was the Confederate South a sea slug worth defending? How could he find Yankee piety disgusting and yet not see all the foolish piety dripping from Lost Cause legends? One answer is that he needed the Confederacy to play the role of the devoured in his drama—the little, misguided David to the huge and imperialistic Goliath of the United States, preparing for its 20th-century career of war and expansion. Another is that Wilson really did not believe slavery was the cause at the heart of the sectional crisis; he believed slavery had never been anything but a “pseudo-moral issue” and the purpose of his book, he contended, was to “remove the whole subject from the plane of morality.” And lastly, we might understand Wilson’s apparent Southern sympathy by looking at his use of analogy. A favorite was his comparison of the plight of Hungary in the Soviet invasion of 1956 with that of the seceded Southern states invaded by Union armies. Moral equivalence is a dangerous rhetorical tool, but Wilson employed it happily and sometimes recklessly. “In what way,” he asked, “was the fate of Hungary, at the time of its recent rebellion, any worse than the fate of the South at the end of the Civil War?” Well, the outcome for the Hungarian worker crushed under a Russian tank and the white Georgian farmer killed during Sherman’s march might be identical. But Wilson needed to learn more about Reconstruction to make the link between the strangleholds the Soviet army and the Union army had on their respective foes. The Soviet army really did occupy Budapest a great deal longer and with much more lasting consequences than Yankee troops ever interfered in the lives of ex-Confederates.

Courtesy the National Archives and Records Administration.

But Wilson pushed his analogies even further. In a beguiling comparison, Wilson argued that the three great leaders of the modern “impulse to unification”— Lincoln, Bismarck, and Lenin—all became heroic but detested “dictators” for their respective causes. Each was “confident that he was acting out the purpose of a force infinitely greater than himself,” Wilson intoned. Bismarck believed in “God,” Lenin in “History,” and Lincoln in some kind of democratic combination of the two. All three, though, according to Wilson, were mere agents of the “power drive” that moved nations and history over and over into mass violence and conquest. It is remarkable how Wilson could write so freshly and so cynically at the same time. He believed that Americans just could not look closely at their own violent past and present. In 1962, only a few months before the Cuban Missile crisis made everyone look at the prospect of nuclear extermination, such a test of the imagination may have been a good thing.

Wilson scorned the superficiality of the Civil War’s official commemoration (what he called “this absurd centennial”) of the late ’50s and early ’60s with his critique of the “panicky pugnacity” of the two sea slugs in the Cold War. “A day of mourning,” Wilson wryly offered, “would be more appropriate” as a means of public remembrance of the blood of the 1860s. Before settling in to restore Harriet Beecher Stowe and Ulysses Grant and their host of odd companions to an American literary pantheon, Wilson had first tried to settle a score with his demons of war and nationalism, and perhaps some other demons as well.

***

Upon publication in 1962, Patriotic Gore became a literary sensation. It was the rare book that seemed to make virtually everyone in the thinking-literary class stand up and take notice. One reason so much attention was paid to Patriotic Gore, as one reviewer after another remarked, was that is was so “genuinely serious,” so startlingly unusual amid the “flapdoodle,” the “dressed up” “vulgarities and tomfooleries” of Centennial books, pamphlets, re-enactments, facile speeches, patriotic commissions, pursuits of minutia, and other Blue-Gray sentimentalism. The literary class, from critics to historians to poets and novelists, seemed grateful that someone had spent all those years going back to explore whether the Civil War had actually left any serious cultural stamp on the country.

Many impulses drove the enormously positive response to Patriotic Gore, but none more than the encounter with Wilson’s sense of discovery about the writers, diarists, and orators celebrated in the 775 pages of the body of the book. “Patriotic Gore is not really much like any other book by anyone,” gushed Elizabeth Hardwick. She admired Wilson’s ability to find the Civil War’s literary “harvest,” of which she seemed utterly unaware. Hardwick gave herself over to Wilson’s portraits of the famous Lincoln or the forgotten Kate Chopin or Albion Tourgee.

Wilson chose his subjects in his own idiosyncratic ways. There are many obvious writers included (Harriet Beecher Stowe, Lincoln, Ulysses Grant, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and Ambrose Beirce) and some obvious ones who make only brief, if sparkling, appearances (Nathaniel Hawthorne, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, and Henry James). The most gaping whole in his otherwise remarkable array of writers is African Americans. Wilson simply took no interest in black literature, and seemed completely unaware of slave narratives, especially that of Frederick Douglass, whose first autobiography (now a canonized classic) came back into print in 1960 after many decades of obscurity. Wilson’s strange, but not strange, ignorance of virtually any black writers or orators of the Civil War era tells us much about Wilson’s own moral blindness, but even more perhaps about the state of knowledge in elite white circles of African-American history and letters in the 1950s and even early 1960s. But the chapters of Stowe, Grant, and Holmes, in their excited appreciation and probing analysis, alone make the book worth reading. Holmes, the devastated wounded soldier turned realist-jurist and brutal critic of Gilded Age greed and materialism, is Wilson’s ultimate hero.

But who knew that the travel writings of Frederick Law Olmsted, who was much more famous as the designer of Central Park in New York, or the poet, John T. Trowbridge, provided such vivid depictions of slavery and the ruined South both before and after the war? Who in 1962 had read the diary of Charlotte Forten, the romantic, educated young black woman (the only one in the book) who went South during the war to work among freedmen, or the important Army Life in a Black Regiment by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, the Massachusetts abolitionist who became a soldier overnight and a student of slave musical culture? Who understood by the mid-20th century that such Confederate soldiers as Richard “Dick” Taylor, son of President Zachary Taylor, and John Singleton Mosby, notorious cavalry raider and bandit, had written such fascinating and richly literary memoirs? And did anyone but the rare specialist know that Mosby, who had captured and killed many of Grant’s men during the war, became the former general and president’s good Republican friend by the end of Reconstruction?

How many white Southerners, or anyone else for that matter, understood just how complicated proslavery ideas were when comprehended in the “diverse” writings of William J. Grayson, George Fitzhugh, or Hinton R. Helper, the latter of whom tried desperately to get the South to modernize its agriculture if not its racial views? Did even the most literate Americans in either section know of the advanced racial imagination of a Northerner like Tourgee and his now classic, A Fool’s Errand, or the remarkably progressive and prolific Louisianan, George Washington Cable, whose Grandissimes in fiction and The Silent South and the Negro Question in nonfiction earned him a forced exile to New England for his safety? Indeed, how many Americans even now know of Tourgee’s complex personal critique of the Ku Klux Klan or of Cable’s early and forthright engagement with racial mixing well before William Faulkner? This list goes on: how many literate Americans were at all aware of the eloquent Confederate women diarists—Mary Chesnut, Kate Stone, and Sarah Morgan—who left such extraordinary visions of the tragedy of war rendered with wit and haunting despair? These writers and more provided the wave of surprises that made Patriotic Gore such a revelation in the season of Centennial fatigue.

Wilson over-wrote some of his portraits and self-indulgently over-quoted some of the writers. The book wanders from soldiers to poets and diarists and back to soldiers once again without obvious organizational logic. Eventually, in the self-appointed role as judge of taste and significance, Wilson seems to just follow his whimsy. He would wear out most readers with his over-blown discourse on John W. De Forest, former soldier and author of Miss Ravenal’s Conversion to Secession (which Wilson judged as the book in which American realism had been born), and leave many dumbfounded why an obscure poet like Henry T. Tuckerman occupies more space than Whitman or Herman Melville.

But in his inclusion of numerous relatively unknown writers, and the sheer virtuosity of his insights, Wilson provided a feast for all who came under his spell. As the historian Richard Current commented in a review, Wilson was to him “naive” in some of his historical understandings, as long-winded and disjointed as an “anthology,” and narrowly limited in his judgments of Southerners because of a single-minded fascination for states’ rights and Alexander H. Stephens, the vice president of the Confederacy. But Current loved the book nonetheless, claimed Wilson’s “fascination will infect any reader,” and said the work was “not nearly long enough.” And Lewis Dabney, Wilson’s eventual biographer, addressed the question of the complexity and cacophony of Patriotic Gore’s cast of characters. “Reading it,” wrote Dabney, “is indeed a little like being set down in a room packed with people, each and everyone of whom wants your ear for however long it takes to tell of himself or of others, of great or sorrowful events. … Putting himself on the sides of his characters, Wilson also speaks over their shoulders in his own voice.”

Dabney’s image helps us understand the book’s purpose—writers portrayed as historical actors through intriguing biographical portraits and the critic there when we need him, reminding us how the wielders of words and ideas are the drivers and reflectors of history. And thus, such major critics as Irving Howe and Alfred Kazin called Wilson the “American Plutarch.” The writers’ lives, as well as their works, are always Wilson’s combined subject.

***

Most of the writers included in Patriotic Gore are either participants in the bitter debates that led to war, warriors themselves, or veteran-participants who lived to tell of the war in memoir, fiction, or public orations. They are women in their diaries at home and men in high office. They are all witnesses to an epic event full of convulsion, blood, and sacrifice, and from which Americans are always expecting a redemptive, progressive story. But the unsentimental Wilson steadfastly would not give them that. Such redemption hardly intrigued him at all, unless of course that was the grain in or against which his subjects wrote.

The astute and patient reader of Patriotic Gore has to step in close and then back up again, as in viewing impressionist paintings, as a means of seeing Wilson’s recurring themes. Above all, the book is shot through with Wilson’s quest to reveal and explain the competing myths of Northerners and Southerners caught up in this struggle for national and regional existence. Like Robert Penn Warren, who wrote so probingly about Civil War memory in the same era, Wilson was convinced that people live by myths – the stories from which they draw meaning and identity – as they experience history.

The war may not have produced a literary Iliad, but it certainly had produced the swirling myths that forge competing epics in national memory—the righteous, abolitionist North acting out its destiny, saving the Union by purging the land of its sins in the necessary blood that John Brown had prophesized on the Christian gallows of Harpers Ferry; and the noble, Southern aristocratic defense of the old republic, its ordered, limited government and its honorable, even gallant bulwark against the leviathan of capitalism and the alienation of industrialization. Both the Northern and Southern epics enlisted God or Providence on their side; the apocalyptic destruction of slavery or its humane, eternal improvement might be the divine plan. The house divided had been sundered over rival, incompatible stories, which since the war had thrived as folk epics. Some reviewers called Wilson a “myth breaker” or “Civil War debunker,” but those likely did not read past the Introduction. Wilson understood myth as astutely as any literary historian could; he also enjoyed finding and analyzing the true artfulness of myth-making. He did not much sympathize with one of the war’s enduring myths, the abolitionist piety of Yankees, their stern religious certainty that they knew what was best for the country in its dilemmas with slavery and race relations; he preferred the brilliant probing of Harriet Beecher Stowe in her artful creation of characters in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Wilson found most proslavery writers largely contemptible and backward, but he grudgingly admired the art with which some Southern memoirists defended their cause of military resistance.

To Wilson, myth was not something to be lampooned or wished away in favor of an accurate history. It was to be breathed in, appreciated, countered by careful exposure. Myths can be dangerous, but also strangely fascinating in their uses and abuses. As Warren aptly said of Patriotic Gore, its great aim was to prompt us to “criticize our myths and, even, to enrich them.”