The following is excerpted from Jon Katz’sThe Second-Chance Dog: A Love Story which is being published next week by Ballantine Books.

I heard the barking as soon as I pulled into the gravel driveway of the sprawling old farmhouse on a country road about five miles from my farm. The noise was coming not from the house but from a barn behind it.

It was the deep-throated, door-rattling roar of the guard dog, and there was something undeniably frightening about it. A dog with a voice like that had to be huge and powerful. I had never heard a roar quite like it. None of my dogs ever barked in such a furious, almost panicked way. It was a bark to be taken seriously, very seriously, and I was reminded of the raptor in Jurassic Park busting out of its prison.

I was not looking for trouble from a dog. My life, at this point, was in upheaval. I was spectacularly disconnected from the world and attempting to stave off a crack-up. I tried to soothe my internal turmoil by focusing on fixing up my collapsing Civil War–era farm and barns, at least three of which were about to topple over into the road. Barns were collapsing and being torn down all over Washington County, N.Y., where I lived, but I was determined that my four would be saved. This project was horrifically expensive and complicated, but I couldn’t bear to see these beautiful old structures disintegrate.

I wanted some old windows to put in one side of my big dairy barn so that the grand old red silo housed inside the barn (an unusual feature) could be seen from outside. No real farmer would consider such an insane thing. But at the time, I was not sane. An HBO film crew had just finished making a movie of my trek upstate, and the very air was suffused with unreality.

So, I had come to this place because I’d been told that the couple restoring this farmhouse had some old windows. A thin, wiry woman with short brown hair, wearing tattered jeans, a paint-splattered shirt, and sandals, came out of the door and approached me. As we stood in the drive, she began urging the dog to calm down. “Ssssssh, Frieda, quiet,” she said. Her voice was so soft and tentative I knew she didn’t really mean it, and the dog surely knew she didn’t. She was concerned that I might be frightened, but I can tell when somebody means to change a dog’s behavior and when they don’t.

“We can’t have many people over.” She smiled, tilting her head back toward the frenzied roaring and charging coming from the small barn.

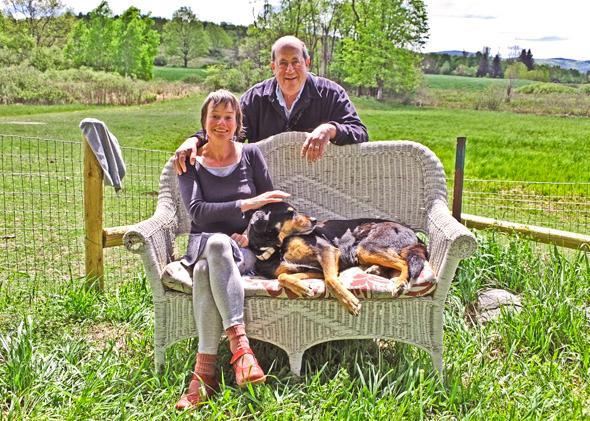

Photo courtesy Jon Katz/Ballantine Books

There was something melancholy about this woman. She was so quiet and reserved. She shyly explained that she and her husband were living in a small barn while they fixed up the farmhouse close by. “Who is that?” I asked, gesturing toward the barn, whose door was still rattling from the force of the dog inside throwing herself against it.

“That’s Frieda,” she said, surprising me with a radiant smile.

“Nice to meet you,” I said. “I’m Jon.”

“I know,” she said. “I’m Maria. I have to confess,” she continued, “I haven’t read any of your books.” She was small, frail, almost elfin. But I knew I saw some humor in her eyes, attitude, pride. She was restoring houses with her husband, she said, adding almost under her breath that she was also an artist.

“That’s OK, most people haven’t. Anyway, I can give you one,” I said, reaching into the car. I had brought a paperback with me.

I don’t know why I’d brought a copy of that book—it was The Dogs of Bedlam Farm—for Maria. She looked at it and laughed, and would soon put it aside.

Maria invited me into the barn, into the small room she was living in while working on the farmhouse. I hesitated.

I’m not afraid of dogs generally, of course, but I know that in certain situations protective dogs will defend their people and territory. And Maria did not seem strong or clear with Frieda. I could see that Frieda had not been trained, as Maria had no commands to which the dog readily responded. She just got more excited when Maria spoke to her. When people really want their dogs to behave differently, they’re usually more forceful. I have always believed that people get the dogs they need.

Maria needed a guard dog, it seemed. I thought there must be some fear in her. She explained that Frieda did not like men. OK, I thought, so she needed a guard dog who did not like men.

But I wasn’t sure I needed Frieda. She was giving me that unmistakable look of the territorial dog: eyes locked on me, ears back, tail down, body stiff. I had expected to pick up the old windows and leave. But that afternoon, I found myself wanting to talk to Maria. There was something very warm about her. I felt a connection I had not felt in so long I barely recognized it. I wanted to know more, to see what was behind those sad and sweet eyes. My farm is in a remote part of upstate New York, and I had not made many friends there. My wife at the time was living in New Jersey, and our visits to see each other were becoming less frequent. It was sometimes lonely. Actually, it was always lonely.

We walked to the barn, and the roaring got even louder. Maria opened the door ahead of me, and I could see her lean over a large brown-and-black mixed-breed dog and pull her back into the corner. The roaring subsided for a bit, and then resumed from the corner. Frieda wasn’t trying to charge me; she just clearly wanted me to go away. She was more anxious than aggressive.

I could see right away that Frieda—a Rottweiler-shepherd rescue—was like others I had met: loving and devoted to their humans, but ferociously protective of them. Because I write about dogs, people are sometimes embarrassed when I meet theirs. They suspect I am judging them, and they apologize. The dog was abused, the dog was abandoned, the dog is sweet and good, just overprotective in some situations.

Maria apologized for Frieda’s barking. She had never really trained her, she said, but it didn’t seem to me that Maria was too bothered by Frieda’s loud vigilance.

Still, I have studied attachment theory for years, written books about it, lived it in my own life. It is a prescient window into the lives of some people, how they are with their dogs, how their dogs are with them. Something powerful connected these two.

I looked around the barn. I could see that Maria and her husband were living an ascetic life. No computer. Few possessions. Nothing new or fancy. A spartan place, almost monastic. Lots of books and magazines. No junk or clutter. Different from my life, filled as it was with rolling chaos.

Maria repeated that she couldn’t really have many visitors. And she didn’t trust Frieda outside, either, around people or other dogs. “I take her for long walks in the woods,” she said, “but it’s just us.” Maria didn’t think Frieda was trainable because of the dog’s history, and because she was so wild.

She had adopted Frieda from a local animal shelter, where she had been kept for nearly a year. All the shelter workers knew about Frieda was that she was a healthy female (the shelter had spayed her) who had been captured in the southern Adirondacks after a yearlong pursuit by one of their animal control officers.

I have kept away from dogs like Frieda all of my life, and would never have considered adopting one or taking one home. For me, dogs are about people, mixing with them, living among them. I would not want a dog that people were afraid of, that you had to watch every second. And looking at Frieda, whose barking had now morphed into a low, menacing growl, I was definitely wary of her.

But I had seen this type of situation before. Sensitive people (often, but not always, women) empathized with dogs who would be put to sleep if they were not adopted, who desperately needed homes. And I knew there was often something else going on. Perhaps a wish to be protected? A complicated childhood? A desire to withdraw from the world? A need to nurture? All of the above? None of the above.

I moved a couple of feet inside the barn, and when Frieda roared and growled, I moved back again.

So there it was, the beginning of my fairy tale, the kind of story men my age are not supposed to dream of anymore.

“What made you adopt her?” I asked. The answer would tell me a lot about this woman, and I almost always ask it of people I meet with big, scary dogs.

“Oh, I just thought she was so cute,” she said. I smiled.

Photo courtesy George Forss

This is the story of an aging and troubled man yearning for love and knowing it will never come, a troubled artist who had given up her art and lost her voice, and a courageous, fiercely loyal wild dog abandoned by a bad man and left to fend for herself in the Adirondack wilderness.

There was me, 61, broke and bewildered, beginning to see that his 35-year marriage was falling apart, living alone on a farm in a poor and remote corner of upstate New York with a bunch of animals.

And there was Maria, a sad, brooding fiber artist in her 40s, nearing the end of a 20-year marriage, seeking to find her lost creative soul.

And finally there was Frieda, aka “the Helldog,” a Rottweiler-shepherd mix who had been cruelly abandoned and spent years living in the wild.

And what in the world could possibly bind these three completely disparate and seemingly so utterly different beings? The thing that makes any good fairy tale work: We were looking for love. We were looking to be saved from an empty life. We were seeking that rarest of miracles, a second chance