Please send your questions for publication to gentlemanscholarslate@gmail.com. (Questions may be edited.)

Troy,

I know far too many men whose go-to photo face has become that zany one-raised-eyebrow thing that twentysomething dudes are fond of affecting these days. Here and here and here are some examples and you’ve undoubtedly seen many more. It has touches of Dr. Evil but, like, a winking, clever version, or so the eyebrow-raiser seems to think.

What is happening here? What is this thing? Can you explain it to me or at least attempt to name it or talk me through it? Yes, yes, these boys are a little shy about posing sincerely for the camera and try their best to put forth their most convincing I-don’t-give-a-damn, but is there more to it? Is this the unfortunate male equivalent of duckface? And how does a modern gentleman who’s concerned with being, like, authentic and aware all the time photograph so he avoids coming off like his sole mode of humor is sarcasm?

Curious,

Anastasia

My camera-wary brethren thank you for your concern, Anastasia, and my publisher appreciates your assistance in keeping this column on trend. Have British bookmakers begun taking bets on the Word of the Year awards? If so, what odds are they laying on selfie?

It has been seven years since the Styles desk of the New York Times identified the self-portrait photograph as “a kind of folk art for the digital age.” The headline was “Here I Am Taking My Own Picture,” and the sources included Guy Stricherz, the creator of snapshot anthology titled Americans in Kodachrome, 1945-65. “Mr. Stricherz said he reviewed more than 100,000 pictures over 17 years in compiling the book but found fewer than 100 self-portraits,” the paper explained, proceeding to calculate how quickly you could find 100 self-portraits as many checking out “MySpace, Friendster, and similar social networking sites.” Oh, we were all so young then, back in the early days of the self-surveillance state.

At the end of February, Instagram passed a numerical milestone—100 million users serving avatars to one another—and the media, in the course of reporting on the masses reproducing images of themselves and attending to the self-publicity of entertainers, have since ushered the word selfie into mainstream vocabulary. Check the spanking-new Wikipedia entry. The word selfie is catchy, perhaps, in its cuteness. The innocence of the fond diminutive makes self-invention sounds like a mere mischievous romp and carries a hint of self-deprecation that takes the edge off the exhibitionism. The word selfie somehow implies that the self-portraitist’s avatar is a bit of cuddly futurism, like some electronic Japanese pet; compare blunt self-shot, with its weaponized ring and its auditioning eagerness.

We have recently seen, in good and bad newspapers, many gentle laments and qualified celebrations of the topic, with pop-socialists twisting such words as “narcissism” and “empowering” away from useful meaning, and CNN interviewing a wedding photographer while wondering if camera shyness is going extinct as a distinct sensation. We will test neither that question, nor the question of exactly how profound a development this is in the history of telecommunications and human relations, what with individuals using seductive machines to build “personal brands,” thus expressing the best and worst of their personalities with robotic efficiency, all to the end of helping corporations to rebuild the relationships among buying and selling and product and marketing and self-image and personal identity. There are light years of cyberspace between the America of Kodachrome and the World Wide Web formed in furious consequence of the minting of Facemash. We are prisoners in a glamorama panopticon of our own devising, and there is no escape, but set all that aside, please. The point is that every gentleman needs one good head shot. You must prepare a face to meet the faces you virtually meet.

If he is compelled to serially confront that dark circle above the screen of his laptop, and if he has pretensions to documentary or artistry (in the tradition of Cindy Sherman or on the model of the hip-hop pixie Kreayshawn), then he should shoot his self-portrait as often and oddly as necessary to achieve his artistic aims.

If he is taking his picture in accordance with the new norms of social media, he is advised to search out natural light, to choose a background that is neither distracting nor dull, to give a moment’s attention to framing as well as to the rule of thirds, and for god’s sake sit up straight.

If he is interested in generating an interesting image, then he might consider the venerable trick of shooting his reflection with a proper camera, so that he is forced to engage with the idea of auto-iconography in a structurally meaningful fashion, using the image of the camera (and the image of the image of the camera) to address his complicated feelings about the process.

And here we return to Anastasia’s question, supposing that the guys raising eyebrows are trying to express a feeling about presenting themselves to scrutiny. They are trying and often failing; they are questioning the camera’s power, but the awkwardness of the image is evidence of the camera having overpowered them. They are attempting irony and clumsily arriving at contradiction. Their superciliousness is an off-putting put-on.

This is to say that the raised eyebrow is an unfortunate manifestation of a healthy tendency. When considering the current media climate—the nexus of consumer technology, the global media business, and your idea of who you are—it is good to cast a skeptical glance. Giving advice about selfies to Nightline, fashion photographer and reality-show beauty arbiter Nigel Barker says, “Don’t pose.” But how can you not, if your ambition is not to merely model a look but to represent the only soul you have?

I am highly sympathetic to the passage in Camera Lucida where Roland Barthes reflects on being forced to pose by the awareness of the presence of the lens, confessing, “I don’t know how to work upon my skin from within”:

“Now, once I feel myself observed by the lens, everything changes: I constitute myself in the process of ‘posing,’ I instantaneously make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image. This transformation is an active one. …

“I decide to ‘let drift’ over my lips and in my eyes a faint smile which I mean to be ‘indefinable,’ in which I might suggest, along with the qualities of my nature, my amused consciousness of the whole photographic ritual: I lend myself to the social game, I pose, I know I am posing, I want you to know that I am posing, but (to square the circle) this additional message must in no way alter the precious essence of my individuality: what I am, apart from effigy.”

The arched eyebrow is a contemporary American edition of Barthes’ sly smile (with its air of the floating sign of the Cheshire Cat). Same dynamic, just less subtle, like its time and place. Perhaps this current period of its prevalence is just a phase. I mean that it could be a phase of the culture; the way that human nature and technology are molding each other, soon Americans will be thoroughly acculturated to performing for the camera with every breath. I mean, also, that it is a phase of the guys’ lives; the guys who are twentysomething now are the same as twentysomething guys have always been—unseasoned, still waiting for their faces to accumulate enough depth of experience to communicate an earnestly manful expression.

Back in my twentysomethings, those of us who’d developed an intuitive mistrust of the camera didn’t have the luxury of being “ironic” by raising an eyebrow. Or maybe our self-irony was of a different kind. In any case, we raised two eyebrows, and we did not feel that the facial gesture was voluntary. Rather, we were self-conscious about being on the business end of a recording device whose importance cannot be underestimated, and we were looking to place some distance between our selves and our shells, returning the glare of the lens with a leery and watchful eye. I have had a hard time shaking the habit, the evidence below will indicate.

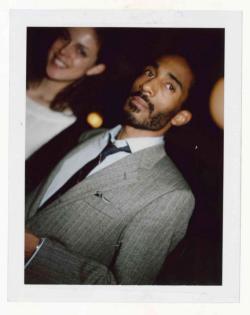

Upon receiving Anastasia’s question, the Gentleman Scholar sketched a plan to model examples (and counterexamples) of how to struggle to comport yourself for a picture. As I say, there is no longer any excuse not to have one good crisp portrait of yourself available at the touch of a finger. (You would count yourself well prepared if it were easily cropped to serve as a passport photo.) This portrait should be professional in both senses: appropriate to a business-class context and created by a photographer who lives by her eye. I called up my friend Christi, went over for pancakes with her family, and we took a couple hundred pictures, with the idea of illustrating the Do’s and Don’ts of what to do with your eyebrows and the rest of that mug of yours when faced with a lens. Also, I wanted to find my literary persona an image more consistent with the Gentleman Scholar’s tone; some commenters had found my current photo rather too rustic in tone, with one even indicating that its mood put him in the mind of Norman Mailer enjoying a post-hunt Glenmorangie.

Photo by Christina Paige

The Don’ts came with ease. A tight smile (as in photo 1) presents the appearance of excessive cheekiness, and the sort of sidelong glance that suggests an airy disregard for the camera (photo 2) risks overcorrection in its air of insouciant self-regard. And don’t forget to have the photographer or another trusted source review the pictures with you. The picture you like because it captures an authentic moment of, say, question-eyed necktie-fidgeting (photo 3), may out of context read as ironic primping. But photo 4 demonstrated the Do: Relax your body but not quite your gaze, square your shoulders, and greet the camera with your chin set at a slight angle.

Photo 4 is the one sort of picture a guy needs in his repertoire—respectable and straightforward while projecting the illusion of personality in consequence of a practiced attempt at what Tyra calls the smize. The Gentleman Scholar was highly tempted to adopt it as his new author photo—but disappointed that it failed to catch the certain snazziness to which his prose pretends. He put the question on the back burner and went over to the bookshelf, where he came across a picture of himself that he liked.

Courtesy of Christopher Bonanos

It was a Polaroid made by the guy who very literally wrote the book on Polaroid, whose name is Christopher Bonanos. The Gentleman Scholar had initiated a conversation with the camera-toting author because he was then fascinated with the ability of instant photography to create a social context, to promote a childlike sense of play, and to exert a concrete analog charm amid all the day’s digital chimera. He is now struck by the book’s mention of an old Polaroid jingle—“It’s more than a camera, it’s almost alive”—and its relevance to the raised-eyebrow pose: a deliberate, forgivable act of assessing an omnipresent animal that’s every moment swallowing the world and spitting out our images.