Scrabble has a new champion. He is Will Anderson, a 32-year-old textbook editor who began playing competitively just eight years ago; his word game of choice before that was Boggle. Anderson won the five-day-long North American Scrabble Championship last week in New Orleans with a 25–6 record, earning $10,000. The runner-up, with a 22–9 record, was 17-year-old Scrabble prodigy Mack Meller. An incoming freshman at Columbia University, Meller achieved an expert rating at age 11, and is now ranked No. 3 among North American players, one spot behind Anderson.

Anderson and Meller faced off three times in New Orleans, including a tense game in Round 21. We got together online to discuss that game and high-level Scrabble generally. The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

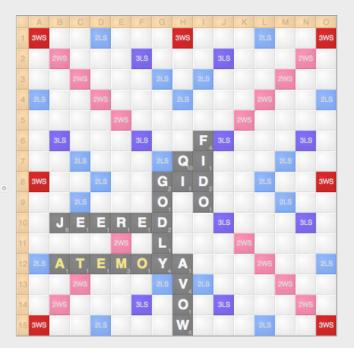

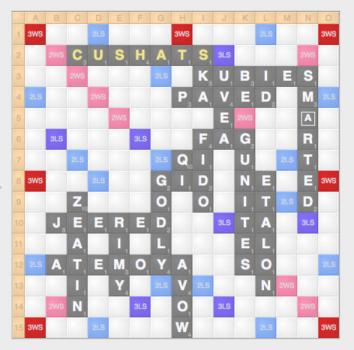

Stefan Fatsis: Let’s set the stage. Will, you’d just moved into first place in the tournament. Mack, you were in third. This is the seventh and final game of Day 3. Mack, you played first. Your letters were—in alphabetical order, as is customary in Scrabble notation—EILOQRY and you made what even for novices is the obvious play: QI, the Chinese life force, for 22 points. The Q is terrible. Dump it while you can.

Mack Meller: QI is the only way to play off the Q, and my remaining letters ELORY leave me in good shape for my next turn. The ER and LY combinations are conducive to bingos.

Fatsis: That is, using all seven tiles at once, earning a 50-point bonus.

Meller: And if I don’t draw a bingo, I can hopefully use the Y for a good score. And another benefit of QI is that it gives Will very little to work with on his next turn.

Screenshot via Quackle

Fatsis: Will was able to play FIDO, defined in the Official Scrabble Players Dictionary as a defective coin, alongside QI for 25 points. Not bad. Will, a couple of turns later, holding AEGIMOT, you did something not intuitive at all. You played a word ending in -YA, which was already on the board. Why did you look there?

Will Anderson: The impetus was dissatisfaction with my other options. Fortunately, I kept looking and found a slightly obscure seven-letter word, ATEMOYA (“a fruit of a hybrid tropical tree”). ATEMOYA scored the most points available; made it more difficult for Mack to use the letters in his previous play, JEERED, to score well; and left the potentially useful GI combination, which would skyrocket in usefulness if I could draw an N, all six of which were still available, creating the very powerful -ING suffix.

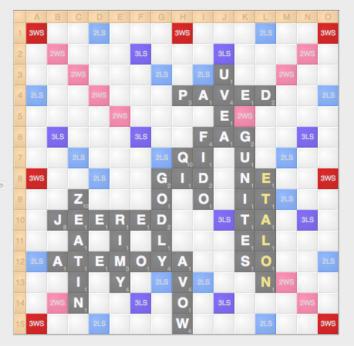

Fatsis: But Mack did manage to score well using JEERED—and ATEMOYA. He performed another act of elite Scrabble dexterity, playing through disconnected letters, in this case the E in JEERED and the T in ATEMOYA. Mack played ZEATIN for 50 points, thanks to the Z landing on a double-letter square and the I on a double-word square.

Meller: I was holding the letters AADEINZ. I’d been all set to play ZAIDA next to FIDO, also making FA, for 44, which is a very solid play in its own right. But it’s always advisable to look near your opponent’s last play for new opportunities, even if you think you’ve already established the best play before he/she moved. This play is a great example: ZEATIN scores six more points, keeps a comparable “leave” (ADE, versus EN after ZAIDA, both of which have good bingo potential), and doesn’t make it as easy for Will to bingo.

Fatsis: But ZEATIN does offer a valuable S hook on the triple-word row.

Meller: That’s true. But plays along that row really have to end in -SH or -SK to cause significant damage. And based on Will’s last play, he probably didn’t keep an H or a K. If he’d had one of them, he likely would have had better scoring opportunities than ATEMOYA.

Listen to Stefan’s interview with Scrabble champion Will Anderson on Slate’s sports podcast Hang Up and Listen:

Fatsis: Will, you responded by also going through disconnected letters in the same two words. You played RIMY for a pedestrian 18 points but kept the letter group GINST.

Anderson: Part of the power of that leave is that it combines very well with some awkward letters, including the W of AVOW. There were a host of two-tile draws after RIMY that would allow me to get an extremely high-scoring bingo starting with W, and that spot was very unlikely to be blocked by Mack on his next turn.

Fatsis: I checked on a word look-up app. There are 29 eight-letter words containing GINSTW, 17 of which start with W. WINGTIPS would have been cool.

Anderson: I ended up playing a different bingo in a different spot on the board. Not that I was complaining.

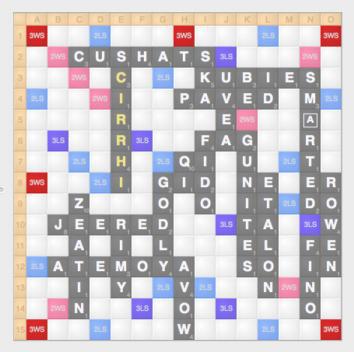

Screenshot via Quackle

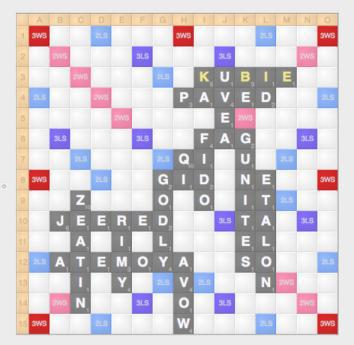

Fatsis: After Mack’s next play, Will is ahead, 179–164. Will, your rack is AELNOTT. There’s no seven-letter bingo, and no R to make the only eight-letter one, TOLERANT. But those are bingo-friendly tiles. Still, you chose to play off most of them with ETALON alongside GUNITES, simultaneously forming five two-letter words, NE, IT, TA, EL, and SO. It’s an aesthetically gorgeous play. Was it strategic too?

Anderson: With the game nearly halfway over, neither of the coveted blanks had been played. So each additional tile I could use increased the likelihood of my drawing one of them. Plus, I was narrowly ahead. Bingoing wasn’t necessary to maintain my advantage, especially on a board with a shortage of opportunities to play seven- and eight-letter words. I was glad to play six tiles for a respectable 27 points.

Fatsis: Mack, your next move was also fantastic: From a rack of BCEIKST, you played KUBIE through the U in UVEA on the third row. It scored 50 points and opened two spots for bingos. And you had just drawn one of the four also-coveted S’s.

Screenshot via Quackle

Meller: As good as KUBIE seems, it was actually far from obvious, since I have another outstanding option: BISK in the bottom left corner, making ZEATINS, for a whopping 61 points. What tipped the scales in favor of KUBIE is, as you mentioned, the fact that I am “forking” the board, creating bingo lines in two different areas—one ending in S on top of KA and the other pluralizing KUBIE. I’ll go up a few points after KUBIE. But after Will’s next play I’ll probably be down again, so I should still play as if I’m trailing by a small margin. It’s beneficial for me to create these bingo lanes, especially since I have an S.

Fatsis: KUBIE is one of 5,000 or so words added to the Scrabble lexicon recently. (It’s a Ukranian hot dog.) I’ve studied the five-letter words, and I’ve studied a lot of the new words. But KUBIE didn’t ring a bell. How do you make sure you can recall a word like KUBIE in the moment?

Meller: Especially with the new words, it took me a very long time to get used to not only being able to anagram them on a word quiz but also actually see them on the board. Now I’ve mostly merged them in my brain with the old words, so there’s not so much of this dichotomy. They’re all just words.

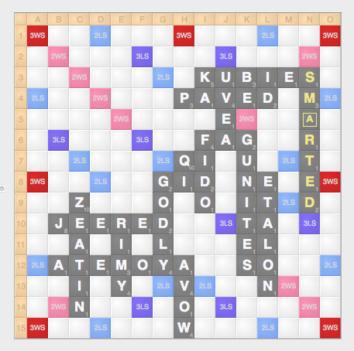

Fatsis: Will, you drew first blood with the blanks and capitalized on one of Mack’s KUBIE hooks, playing SMaRTED (the lowercase letter represents the blank) for 73 points and a 279–214 lead. I always get a little rush when my fingers pull a blank.

Screenshot via Quackle

Anderson: I had a nagging feeling that I was missing something on this turn, and after the game I found out that I was right. SMaRTED is one of two bingos that hook KUBIE, the other being SToRMED, which puts the higher-point M closer to the triple-word score, making SMaRTED slightly better. But despite looking for exactly this type of play in this exact spot, I missed MORTiSED for 81 points through the O of AVOW, making ETALONS, which is far superior.

That’s because SMaRTED allows Mack to respond with very heavy plays along the far-right triple-word column, whereas MORTiSED offers nearly nothing in response. The only saving grace was that, given Mack’s rack, my mistake somewhat helped me, because I got to use the triple-word lane on my next turn. That was an extremely lucky break, which was a running theme of this tournament for me.

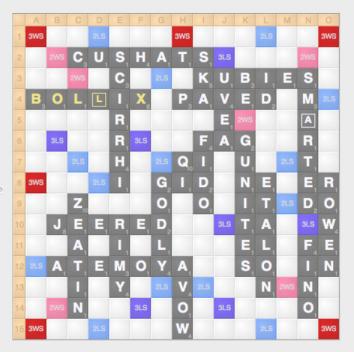

Fatsis: Even the best players can’t win a big tournament without some luck, that’s for sure. At this moment, Will’s break was that Mack couldn’t bingo in the triple-word column. But he did bingo elsewhere. And holy moly, Mack, the word you played is about as improbable as it gets in Scrabble: CUSHATS, the plural of a kind of pigeon. There are 25,257 valid seven-letter words in the North American lexicon. I checked on the word-study program Zyzzyva, and CUSHATS is the 20,202nd least-probable one that can be drawn from a full set of tiles. Did you see CUSHATS instantly?

Screenshot via Quackle

Meller: I did see it fairly quickly. But ironically the least-probable sevens are often the easiest to find, since they generally have more inflexible letter combinations. There are nine sevens in AEINRST, which are all extremely flexible letters. But the letters in CUSHATS don’t work nearly so well. Because of the scarcity of vowels, the SH combo pretty much has to go together, and the second S probably goes at the end of the word as a plural, which limits your options to basically only CUSHATS.

Fatsis: But in order to have recognized CUSHATS you need to have studied more than 20,000 seven-letter words. By way of comparison, I’ve only made it up to 7,500 or so, which helps explain why I was playing in Division 2 at the tournament.

Meller: Believe it or not, CUSHATS almost isn’t the best play here. It scored 77 points. But I have two other very strong options—CUSHAT and ZEATINS for 61 and SAUCH on the right triple-word making ES and DA for 51. CUSHAT keeps the supervaluable S for the SKA hook, and SAUCH has the huge benefit of blocking the triple-word hotspot Will just opened. But scoring 16 or 26 fewer points is just too big a sacrifice to stomach, especially when being down by so much.

Fatsis: Will, after the next two plays, you’re up a smidge, 315–312. You played SCIRRHI down from the first S in CUSHATS for 24 points. The score is close, the tiles are dwindling, and there’s a blank either in the bag or on Mack’s rack. What are you thinking?

Screenshot via Quackle

Anderson: I was feeling some pressure here to play as many tiles as possible, just as I did with ETALON earlier. I’m still hoping to get the second blank, but the other pivotal tile is the X. If Mack had had the X, it’s very likely it would have come down on his previous turn. So I’m definitely hoping it’s still lurking in the bag. The X already plays in a slew of spots on this board, including on the top and bottom of CUSHATS, with XU/XI and AX/OX, respectively, as well as underneath the first A of ATEMOYA with plays like AXEL or AXON.

SCIRRHI creates even more places to play the X. Given that I can’t stop Mack from scoring well if he has it, I’m not really concerned about that. The important thing is that SCIRRHI scores enough points that I’ll only be down a small amount if Mack plays his X for something in the 35- to 40-point range. It also retains opportunities for me to score with the X if I draw it myself.

Fatsis: Will’s now up 339–312. There’s only one tile left in the bag. Mack, you’re holding BGLORX and the second blank. Will, you have AAELNTU. Neither of you knows it, but the P is in the bag. Mack, this is the most crucial turn of the game. As Will noted, there are a lot of places to play the high-value X. Did you have time to fully assess your options?

Meller: I had some time here, I think just under three minutes on my clock, but not nearly enough to fully dissect a close, complicated endgame like this one. So I wasn’t entirely confident I made the correct play, and I had to go a bit more based on general intuition of possible racks than actually playing out all eight possible endgames—one for each of the eight different tiles that, from my perspective, I could draw.

Fatsis: I’m going to interject to say that, yes, top players often consider every possible move by an opponent in the late stages of a game. And that three minutes isn’t much; each player gets a total of 25 minutes to complete all of his or her turns before incurring a penalty of 10 points per minute of overtime.

Meller: I deduced pretty quickly that I was almost definitely going to lose if I pulled a consonant out of the bag. My main problem is that I’m already down 27 points and I can’t score a significant amount without spending the O, the blank, or both. The option that jumped out to me immediately was COX from the C in SCIRRHI, making HO and AX, for 42, leaving BGLR and the blank. This play scores better than all my other options, and keeps the blank for the next turn, so it looks promising. But it has a major drawback: It allows Will to play a word like PA above CUSHATS on the triple-word score, making PAX and AT, for 30. And even with the blank, with four consonants I’m likely not going to be able to play all of my tiles on my next turn, so Will will have two turns to score enough to overcome COX. Playing OX alongside the last two letters in SCIRRHI, making OH and XI, for 39 points, has the same result.

The one exception is if I draw one of the two A’s. In this case, I threaten the awesome outplay of BROLGAs through the O in AVOW, making ETALONs with the blank S. (A brolga is an Australian bird.) Will cannot simultaneously block BROLGAs and score any appreciable amount, so either he scores up top and I go out and win, or he blocks for a few points and I score enough up top to win. So COX wins with two out of eight possible draws.

Fatsis: And you’re seeing all this in real time?

Anderson: Mack processes endgames and pre-endgames faster than almost anybody there is. I can attest that immediately after the game he had most of this worked out.

Screenshot via Quackle

Meller: I remember I was starting to get very low on time, probably just over a minute, after going through the above analysis and was about to play COX when I saw another interesting option: BOLLIX, using my blank for one of the L’s, for 34 points. At first this seems counterintuitive, since it scores less than COX while also spending the blank. But it only keeps the G and the R on my rack, maximizing the chances I’ll be able to play out next turn. I saw that, like COX, BOLLIX wins if I draw an A out of the bag. Then I have two high-scoring outplays next turn: GRAB on the triple-word score to the B in BOLLIX, and AGAR in the bottom left from the first A in ATEMOYA, making GI and AN. Will can’t block both, and his highest-scoring play of APE above CUSHATS loses by a small margin after I go out with GRAB.

I unfortunately didn’t have enough time during the game to exhaustively go over what would happen if I drew the E or the U, but I could sense it would be very close. And my next-best options after BOLLIX can’t be better, since they win with at most an A draw and BOLLIX wins with at least an A draw. So at the minimum BOLLIX is tied for my best play. So I played BOLLIX, saving about 20 seconds to process and play my outplay after Will’s next turn.

It turns out that BOLLIX also wins if I draw the E, but not the U. That means BOLLIX wins three-eighths of the time, which was my best chance in this position.

Fatsis: Will, as Mack is powering through the possibilities, what’s happening on your side of the board?

Anderson: At first, I was alarmed that I had drawn so many vowels, and I was concerned that if Mack made a play that guaranteed him multiple outplays, I wouldn’t have a good way to outrun him. I had identified ALAE towards the bottom of SCIRRHI, also forming ZA, LI, and HI, scoring 24 points, and I hoped this would be enough to keep me in the lead. Otherwise, I was just waiting on pins and needles.

Fatsis: After BOLLIX, Mack takes the lead, 346–339, and he draws the last tile. Because Scrabble players keep track of the tiles as they’re played, Will, you knew that Mack held GPR. Did you realize you had the game won unless you, um, bollixed things up?

Anderson: I saw that given Mack’s lack of a vowel and inability to score very much with those letters, multiple plays through the B of BOLLIX, like ABLUENT or TABLEAU, were going to outscore anything he was able to muster. Another stroke of luck for me in a tournament full of them.

Fatsis: Final score, Will 366, Mack 361. Not the highest-scoring game—Will had a 550-point game in the tournament, Mack had a 597, and the highest score put up by any player (though not of all time) was 697—but a tense and complex one with lots of interesting words. Will, you’re now a hair from being the No. 1–ranked player in North America. And you’ve come this far pretty quickly.

Anderson: This game is deep enough and rich enough that I still feel I have so much to learn and that any given game can surprise me or befuddle me, and winning the championship or achieving a particular ranking is never going to change that.

Fatsis: And Mack, you’re not even in college yet! I first saw you play when you were 10 years old. I think your Scrabble peers are not only convinced that you’ll win a championship but are rooting for you to do so.

Meller: With a game like Scrabble that has a large element of luck, a lot of games are simply not winnable even with optimal play. So all I can realistically ask of myself is to do as well as possible with the tiles I draw. If I do ever get lucky enough to win a championship—and huge congrats to Will—that would be awesome. But I find the true satisfaction to be the challenge of finding the best play given the tiles you happen to have at any given position.

Fatsis: That’s a common sentiment in the upper echelons of the game. After the tournament, another top player, Rafi Stern, who finished fifth, wrote on Facebook, “In poker, I want my opponents to be horrible so that I can walk all over them. In Scrabble, I get so much more enjoyment from hard-fought games against worthy opponents than cakewalks.”

Anderson: Scrabble at its core is a game of solving puzzles, and the puzzles are often better when a game is hotly contested and victory or defeat hangs in the balance. A back-and-forth game with someone of Mack’s caliber is an exhilarating experience. You have to use every last ounce of your brainpower to try and predict what they’re going to do, and figure out how to stop it.