In the 1960s, when chess mavens discovered that Scrabble was a complex game that could be hustled for money, some basic strategies quickly emerged. One of them: Short words are important for scoring. At the seedy Flea House in Times Square, Scrabble’s first obsessives paged through the Funk & Wagnalls dictionary and compiled lists of two- and three-letter words they could deploy in penny-a-point games.

Today’s top Scrabble players go way beyond the “twos” and “threes.” They memorize all of the four- and five-letter words too. And the sixes and sevens and eights and nines. The world’s best players boast arsenals of more than 100,000 words, and they learn how to use them through hundreds of hours of game play and strategic analysis, online and over the board.

Last week, the Wall Street Journal dropped a Page 1 Scrabble bombshell: A group of Nigerian players, led by a new world champion named Wellington Jighere, is “beating the West at its own word game” thanks to a “surprising” strategy that is “changing the game.” Those breathless conclusions might be front-page–worthy if they were true. But Nigerian players have done well for years; Jighere himself finished third in the 2007 world championship. Their strategy also isn’t anything surprising—it’s familiar to players the world over—and it isn’t at all new. It’s the same one discovered by those first serious players a half-century ago: Short words matter.

The story of Scrabble in Nigeria is fascinating, and the Journal’s article, by Drew Hinshaw and Joe Parkinson, explains the cultural side well. Scrabble has been a government-sanctioned sport in Nigeria since the 1990s. Tournaments get corporate sponsorship and offer big cash prizes. Results are reported in the media. When the 32-year-old Jighere captured the 2015 world championship in Perth, Australia, he received a congratulatory call from Nigeria’s president.

“The sponsorship, the media coverage, having Scrabble training groups and curricula makes player development much more effective in Nigeria—and other places like Pakistan and Thailand—than in the more traditional Scrabble powerhouses like the U.S. and U.K., where players are usually on their own to develop their skills and network to find mentors,” says Chris Lipe, a top American player. “That’s a real cool, new thing that’s changing the game at the top levels.” As a result, Nigeria boasts 23 players in the top 100 in the world rankings, compared to 18 for the United States, 13 for Australia, and 11 for England.

Nigerian players do tend to be younger, and flashier, than some of their expert-level counterparts. “Wellington [Jighere] in particular is a really handsome dude, and had some outrageously slick outfits” at a big tournament in Cape Town, South Africa, in February, says American Jesse Day, the runner-up at the 2015 North American Scrabble Championship. Over the board, “there’s a lot more mind games going on than in the States,” he says. “People really smack the clock, and try to pressure their opponent and get in their heads.” Still, Day says of the Nigerians, “they’re a great bunch to hang out with.”

But while Africa’s first world champion is justly worth celebrating, Jighere’s victory didn’t, as the Journal proclaimed, upend some entrenched strategic orthodoxy; there aren’t any Scrabble secrets tucked away in the Gulf of Guinea. Lipe, Day, and a half-dozen other top players we interviewed—we’re both tournament Scrabble players too, and one of us wrote a book about the game—say the Nigerians simply play more defensively than most expert players, using tactics that have been around forever. “They have no magic, I’ll tell you that straight up,” says Nigeria native Sammy Okosagah, who finished third in the 2013 world championship representing the United States. “They didn’t discover anything.”

It’s easy to come away from the Journal story thinking the Nigerians are eschewing “bingos”—words that use all seven tiles on a player’s rack, earning a 50-point bonus—in favor of shorter moves. That’s what Deadspin concluded, dubbing Nigerian players “real Scrabble ascetics who abstain from splashing the most esoteric rack-clearing words they can muster and instead stick to humble five-letter plays.” The headline in the print Journal gave that impression too: “Scrabble’s New Stars Prefer SHORT to SHORTER.” Trust us. If you have the letters EHORRST on your rack, play SHORTER, or its anagram, RHETORS. (A rhetor is a teacher of rhetoric.) If you’re competing outside of North America, where the game features a more-expansive word list, ROTHERS (rother is an archaic word for an ox) also works. Do not play SHORT instead.

The Journal asserted that computer analysis is questioning “that sacred Scrabble shibboleth” of emphasizing seven- and eight-letter words—you know, the ones worth boatloads of points—and “exposing the hidden risks of big words.” Those “risks,” according to the newspaper, are that “every extra letter” on the board offers a dangerous opening to an opponent and that “every letter played gets replaced by a random tile from the bag.”

Those aren’t risks. They’re fundamentals. The beauty of Scrabble is that it’s a game of action and reaction, of skill and luck, embedded in every turn thanks to the elegant board design of inventor Alfred Butts, who tinkered for years to achieve a harmonious balance between risk and reward. When you stick your hand in the bag to draw randomly from the pool of 100 tiles, you can pull manna or junk, whether you’re picking one tile or seven.

Like many sports and games, Scrabble can be played offensively and defensively. At the highest levels, every move involves a complicated calculus of opponent ability, board position, rack content, tile distribution, score, and stage of game. Sometimes a short play is best, sometimes a long one. Sometimes you block the board, sometimes you create volatility. Sometimes you take the highest-scoring play available, sometimes you sacrifice points for better tile “leave” or defense.

Some superexperts, like three-time world champion and five-time North American champion Nigel Richards, are aggressive, scoring in droves but also giving up their fair share of points. Others, like former North American champion David Gibson, are defensive, stingy with the opportunities they give opponents. Gibson, for example, scores about 17 fewer points per game than Richards on average, but his point differential is one point better, since Gibson’s opponents score fewer points themselves. Nigel Richards blows you away like Nolan Ryan. David Gibson wears you down like Greg Maddux. There’s room for all kinds in Scrabble.

What might seem revolutionary to casual Scrabble players—and to reporters—has been studied, deconstructed, and debated in the competitive world for years. The Nigerians do indeed emphasize short words and a tighter, defensive board. But they’ve been doing that since the country’s Scrabble association was formed 30 years ago. “When we started playing, the one thing I told everyone is, ‘I do not have respect for you if you just play nine-letter words,’ ” says Okosagah, who began playing in Nigeria in 1988 and moved to the United States in 1997. “I used to take them back to the Scrabble board and ask them, ‘How many three-letter words do you have? How many four-letter words do you have? How many five-letter words do you have?’ ”

This emphasis on shorter words has led many Nigerians to continue to play defensively even after mastering the vast expanses of the Scrabble lexicon—not always to their benefit. “I think some of them just take it a little bit too far, and then as a result don’t score enough points or end up letting their opponent get back in the game when they were ahead,” says world No. 2 David Eldar of Australia. “It’s certainly nothing new for them. They’ve been playing that way for as long as I can remember.”

An individual’s playing style largely comes down to personal preference. Specific plays, though, can be evaluated empirically, through computer simulation and artificial intelligence, to determine whether a given word choice was the best possible move. In that regard, the Nigerians’ short words sometimes come up short.

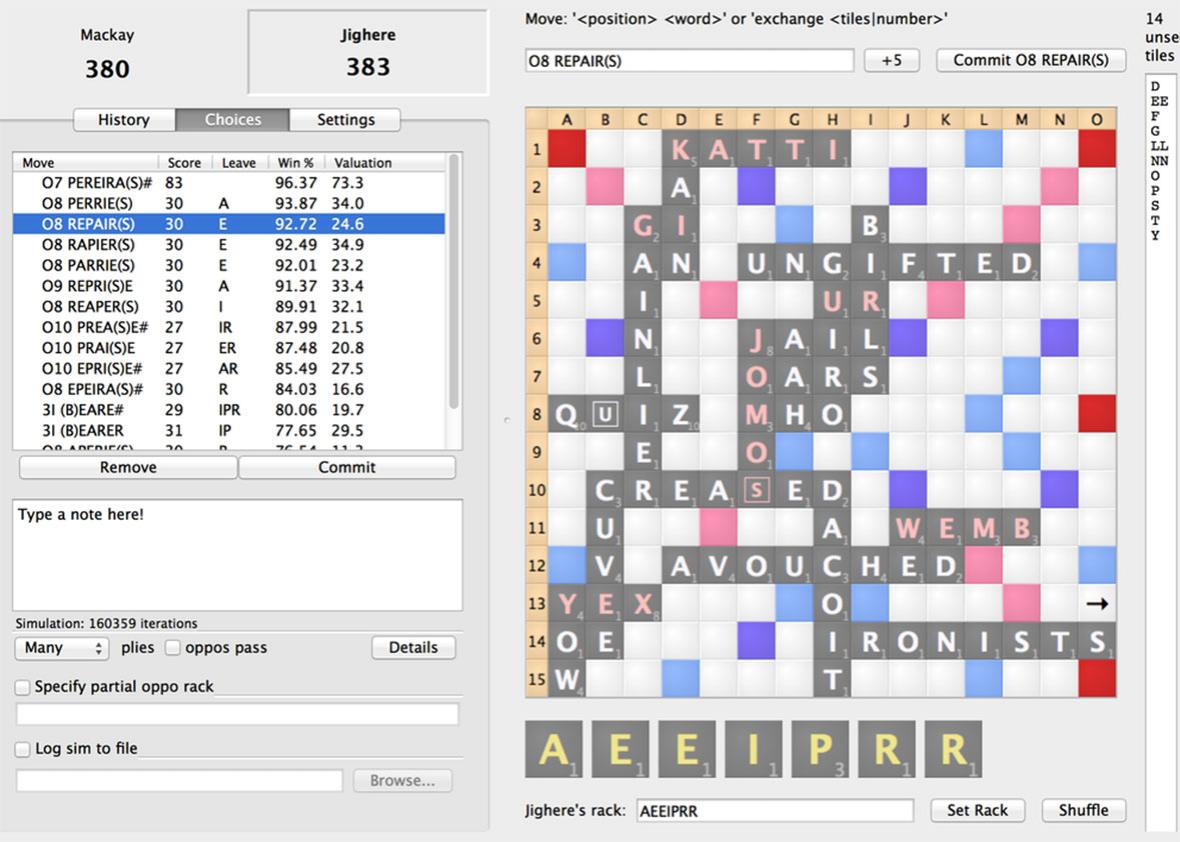

A centerpiece of the Journal’s A-hed is a single play made by Nigerian champion Jighere in Game 4 of the best-of-seven finals in Perth, against Lewis Mackay of England. Late in the game, Jighere was ahead by three points and held the letters AEEIPRR. There was a juicy, wide-open lane down the board’s right edge, passing through a triple-word-score square and ending with an S. Seven tiles sat in the bag.

Jighere could have played PEREIRAS, a kind of Brazilian tree (and a word not acceptable in Scrabble in North America), for a bingo and 83 points. Instead, he played REPAIRS, for just 30 points, keeping an E. The Journal article described this as a purported masterstroke of the “new,” short-word approach to the game. “Champions have studied his defensive style, including his decision to put REPAIR on an S during the final,” the Journal reporters wrote.

Top human players did study the move, at the event and afterward, and came to a different conclusion. “Wellington played a fantastic tournament, but this move is an error, I’m convinced,” says American Evans Clinchy, who finished seventh in Perth. Despite touting the importance of positional analysis and declaring that “a computer revolution has been building in Scrabble” (since the 1980s, actually), the Journal didn’t analyze this all-important position with a computer. And it turns out, according to silicon, REPAIRS was a mistake.

Using the popular Scrabble app Quackle, we simulated thousands of iterations of this position. If Jighere plays PEREIRAS, he wins the game about 96.4 percent of the time, as shown in the table on the left side of the image below. If he plays REPAIRS, he wins about 92.7 percent of the time. It’s not a huge blunder, and either way he’s in great shape. But here, the longer word is better.

Screenshot via Quackle

There is an explanation for Jighere’s decision. From his perspective, 14 tiles are unseen—the seven in the bag plus the seven on Mackay’s rack. The chances are slim that Mackay can bingo using some combination of those letters; Quackle pegs them at about 4 percent. But a bunch of bingos are in fact possible, including SODDENLY, YODELLED, GODSPEED, and STEEPLED, words that wouldn’t be unusual for a player of Mackay’s caliber to spot. (It’s less likely he would have seen the 10-letter STENOTYPED through the T and ED in Column K in the board diagram.)

Jighere certainly looked for those possibilities. He knew that playing PEREIRAS would empty the bag, and that a counterbingo by Mackay would end the game, because there would be no tiles left for Mackay to draw. And he likely determined that, in that scenario, any bingo by Mackay would be enough for the Englishman to win. By playing REPAIRS and leaving one tile in the bag, Jighere gets another turn to try to catch up in the event of a Mackay bingo.

That was a logical thought process. But Quackle shows that Mackay would have won with a bingo either way. That Jighere didn’t figure that out is no criticism; performing such probabilistic calculations under time pressure is extremely difficult. Still, it shows that REPAIRS wasn’t a brilliant, counterintuitive move meriting talmudic scrutiny. It was an educated crossing of fingers.

There are other errors of analysis in the Journal story. The reporters describe Jighere’s play of DACOIT, in the game above, as “terse, defensive.” But playing DACOIT (a bandit in India) is in no way defensive and, at six letters, not exactly terse. It is baldly aggressive, dramatically opens the board, and, according to Quackle, yields more bingo opportunities for Mackay than any other play. It’s a terrific move, one that reflects the situational versatility of all good Scrabble players.

While bullhorning the supposed Nigerian short-word revolution, the Journal left out a critical fact about Jighere’s championship win: It was decided by bingos, or the want thereof. In sweeping the finals four games to none, Jighere bingoed 12 times to Mackay’s six. Those 12 bingos were an impressive haul even for expert players, who average around two per game. And a missed bingo cost Mackay dearly.

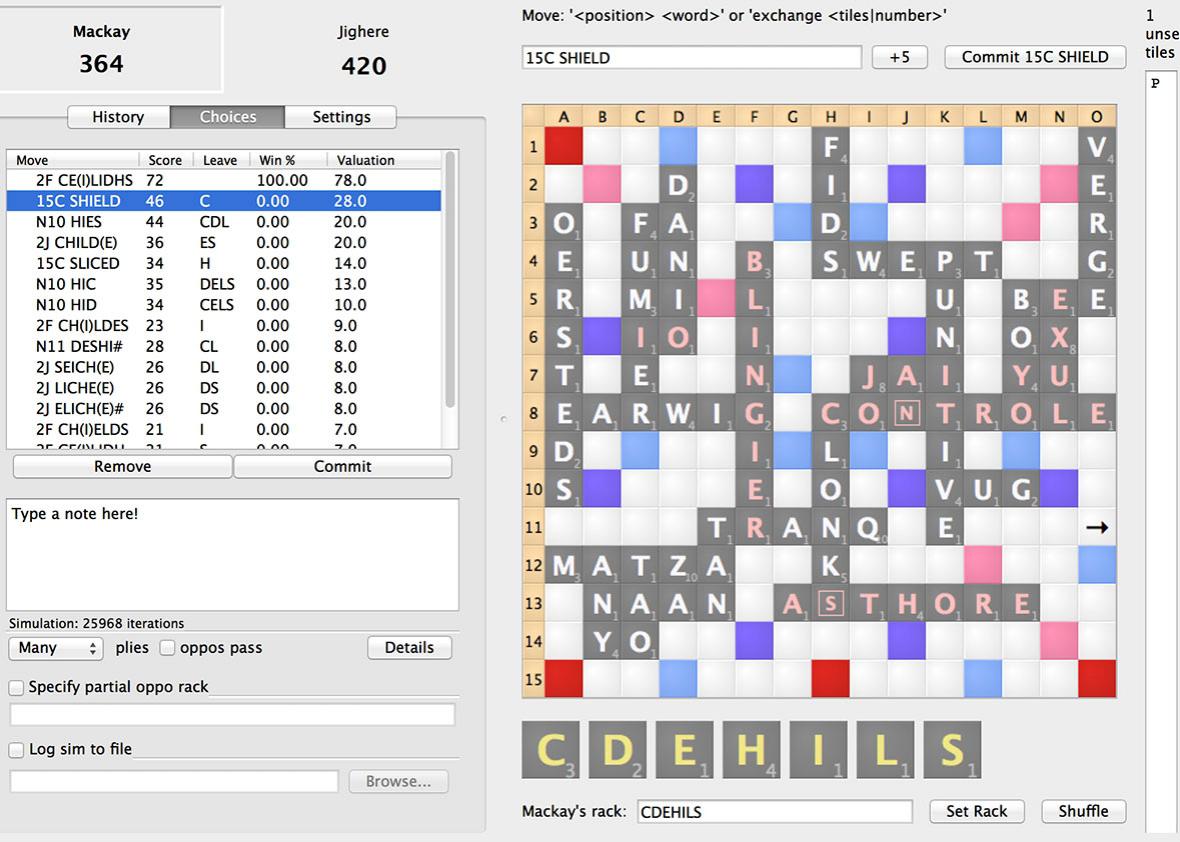

Screenshot via Quackle

Toward the end of Game 2, trailing by 56 points, Mackay held the rack CDEHILS. He played SHIELD along the bottom row, also making TAOS (the plural of TAO), for a total of 46 points. Had Mackay found the one playable bingo—CEILIDHS, through the open I on the second row for 72 points—he would have won the game. CEILIDHS, the plural of a word meaning an Irish or Scottish party, isn’t exactly common, but it’s still a bit surprising Mackay missed it, given the best players’ extensive word knowledge and fast-twitch anagramming skills.

In competitive Scrabble’s early days, word knowledge was hard-won and closely guarded. Three-time North American champ Joe Edley famously gained his in the late-1970s while working as a night-shift security guard, where he memorized the paper pages of the first edition of the Official Scrabble Players Dictionary in the quiet hours. David Gibson learned the words by studying handwritten flash cards and meticulously annotating his hardcopy OSPD. Over the past 20 years, word study has been democratized, and drastically streamlined. The Scrabble word lists are accessible online, and there are devoted digital word-study apps like Zyzzyva. The powerful analysis tool Quackle is free to download. There are also countless customized lists organized by word length and letter and probability and playability and vowel content and prefixes and suffixes and subject matter, from currencies to birds to fish.

The Journal story seems to suggest that the Nigerian players stumbled across some lost pages of the Scrabble dictionary. Using computer analytics, the newspaper reported, the Nigerians “came up with a secret list of the five-letter words that are hardest for opponents to utilize, code-named ‘ajuwires,’ Nigerian slang for an intern.” The idea of a “secret list” today is absurd. Top players the world over know all of the five-letter words and, at least to a rough approximation, the entire rest of the dictionary. “It’s not like the fives are a secret weapon that no one else in the world knows about,” Clinchy says.

None of this is meant to imply that “short words” aren’t powerful. They are, overwhelmingly so, which logic and computer analysis support; if you only learn one Scrabble word it should unquestionably be the very short QI. But the importance of shorter words doesn’t represent some sea change blowing in from across the Atlantic. “In general, passing up bingos to make shorter plays is a thing that happens in Scrabble,” Clinchy says. “But it’s very rare, and the authors [of the Journal article] clearly don’t understand the nuances of when and why it happens.” (Two examples of when skipping a bingo does make sense: You’re holding a blank and can score 40 or more points without burning it; late in a game when bingoing is the only way to give your opponent a spot to play that would allow him to win.)

Nevertheless, the ever-confident Journal reporters are all in on their flawed premise. “Get back to me when you get your rack management to Nigerian levels,” Hinshaw snarked at one of us in a tweet. “I’ll be in Lagos, learning from the champs.”