There’s a huge scandal raging in the crossword world, bigger even than when the New York Times put SCUMBAG in 43 Down. This past Friday, Oliver Roeder of FiveThirtyEight exposed the possible cruciverbal malfeasance of USA Today and Universal Syndicate crossword editor Timothy Parker. In his examination of Parker’s work, Roeder discovered “more than 60 individual puzzles that copy elements from New York Times puzzles. … The puzzles in question repeated themes, answers, grids, and clues from Times puzzles published years earlier.”

Parker pleaded innocent in an interview with Roeder, saying that the copied elements in his puzzles are “just mere coincidence.” He told Roeder, “We don’t look at anybody else’s puzzles or really care about anyone else’s puzzles.” (Slate reached out to Parker for comment and he did not reply.) In the aftermath of Roeder’s piece, Parker will “temporarily step back” from his roles at USA Today and Universal while his employers conduct an investigation. (In response to a request for comment, Universal Uclick—which owns the copyright on both the USA Today and Universal puzzles—sent a link to its statement from Monday, in which it said in part, “We are taking the allegations very seriously, and will explore them thoroughly and quickly.”)

That investigation into Parker’s work shouldn’t take very long. As a professional crossword constructor, it is extremely hard for me to believe that what happened here is a mere coincidence.

Building on Roeder’s work, let’s drill down further into Parker’s main defense, which is that crossword puzzle themes sometimes do get innocently repeated.

This is absolutely true, as I discussed in a Slate piece in 2009 after I wrote a crossword whose theme entries all embedded the word RAVEN—a theme someone else had used a few months prior. But that doesn’t appear to be what’s happening with the Parker puzzles.

To understand why, I’ll run through some examples that I’ve rated on a “Crossword Suspicion Scale.” A puzzle that looks to be innocently duplicated will be a 1 on our scale. One that appears to be straight up plagiarized will rate a 10.

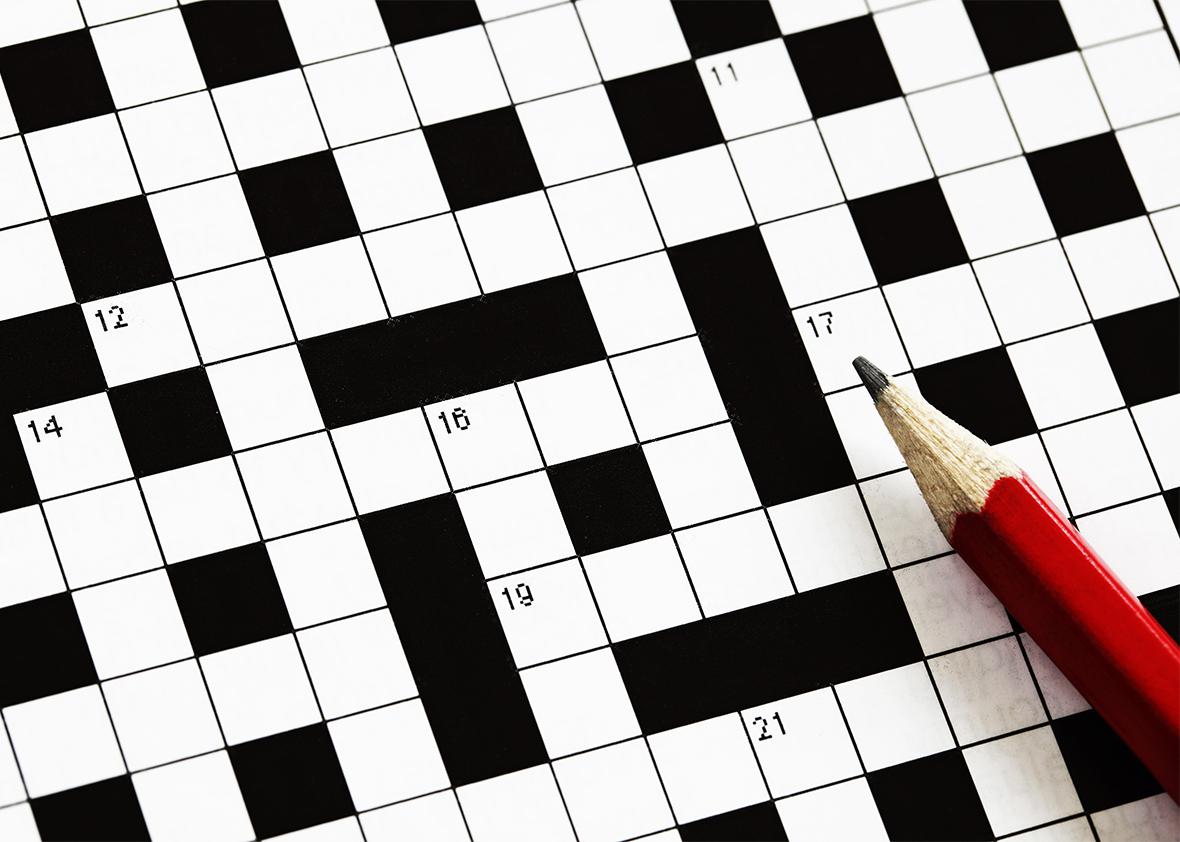

Here’s what a 1 looks like on the Crossword Suspicion Scale. (That link goes to a crossword database compiled by Saul Pwanson, whose work helped uncover the similarities in Parker’s puzzles.)

Image by Matt Gaffney

On July 7, 1994, the New York Times (on the left) published a crossword whose theme entries were a humorous Oscar Wilde quote chopped up into three pieces: TO LOVE ONESELF IS/ THE BEGINNING OF A/ LIFELONG ROMANCE. On Oct. 15, 2002, USA Today ran a puzzle with the exact same quote, chopped up in the same way, with exactly the same placement of theme entries.

Plagiarism? Not remotely. This Wilde quip is catnip for crossword writers. We all scan quotation sites looking for themes, and this is one that would catch any constructor’s eye: It’s genuinely amusing, it’s by a famous writer, and most importantly, it breaks up into three 15-letter theme entries. Even the syntax cleaves nicely along the three lines—this may be the most crossword-suitable quote of all time. And of course the three entries will be found in the same positions in both puzzles, following the order of the quote.

In fact, this quote works so well as a crossword theme that it’s been used in the Times twice before, in 1985 and 1992 (both of those before Will Shortz took over as the NYT’s crossword editor). This is about as unsuspicious as a crossword with duplicated theme entries can be.

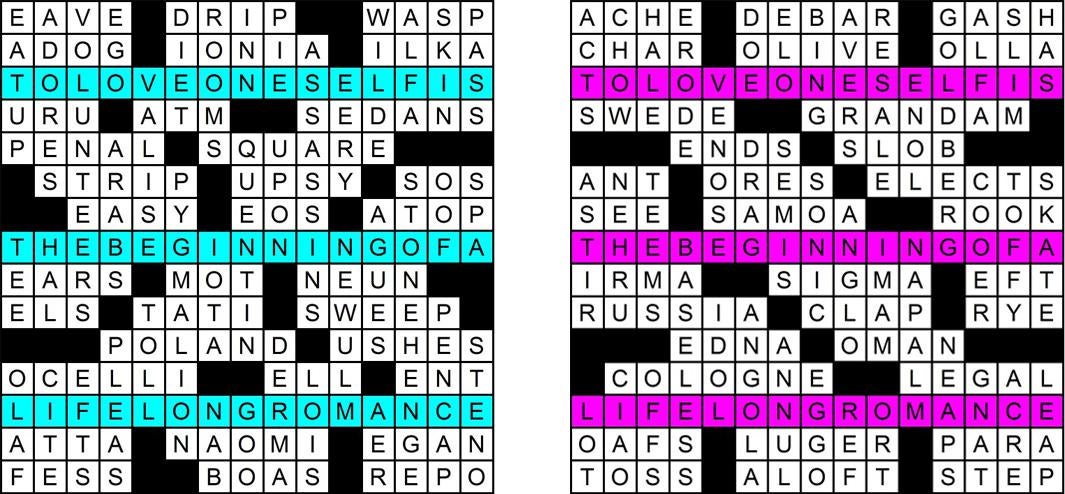

Now here’s what a 4 on the Crossword Suspicion Scale looks like, with the NYT original (on the left) running in 1997 and the USA Today version in 2007:

Image by Matt Gaffney

The three theme entries are I’LL THINK ABOUT IT, MAYBE YES MAYBE NO, and ASK ME AGAIN LATER. That’s a reasonable set, but the last two are a little off: Judging by Google searches “Maybe, maybe not” and “Ask me later” are each far more popular phrases than these slight variants. The theme entries are also in the same order in the NYT and USAT grids, which was not a given here, unlike in the quote puzzle above. Why did neither constructor use other 15-letter options like I’M NOT REALLY SURE or I’LL GET BACK TO YOU or IT’S A POSSIBILITY?

You may notice another similarity: The pattern of black squares in the two grids is identical. There are a few dozen common grid patterns for a crossword anchored by three 15-letter entries, and this is one of them. That additional commonality bumps this puzzle from a 3 to a 4 on our scale.

Overall, this puzzle would raise some suspicion, especially as part of a larger pattern, but by itself it’s not anywhere close to a slam dunk. Two constructors could have come up with this theme independently. It’s slightly unusual, but unusual things happen all the time.

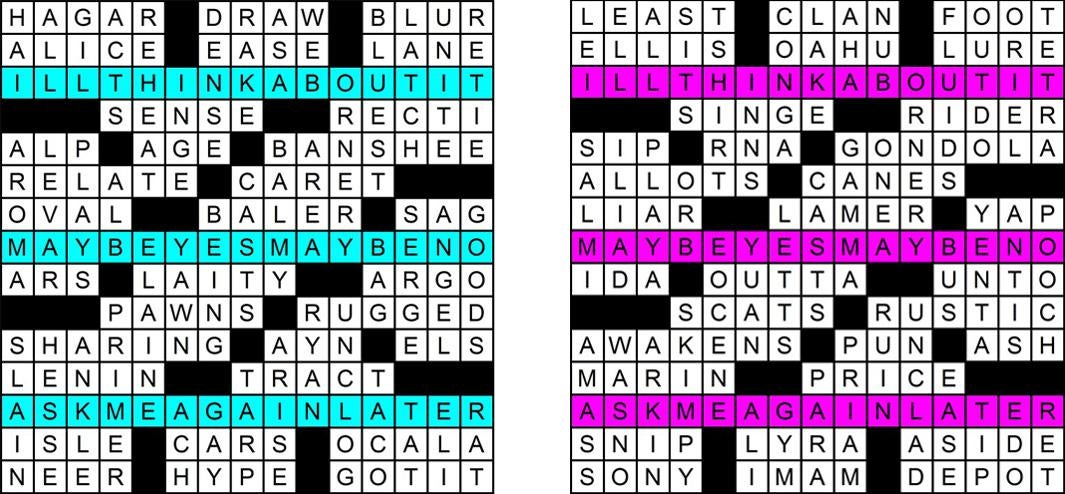

Let’s take a look at a 6 on the Suspicion Scale, where the benefit of the doubt starts to get tougher to grant:

In 1997, the NYT (on the left) ran a puzzle with a simple theme of RABBIT EARS, HAREBRAINED IDEA, and BUNNY SLOPE. The Universal Syndicate ran a crossword with the same three answers 10 years later.

Three identical theme entries, and in the same order, but it’s a pretty obvious idea and there’s not a whole lot of wiggle room with the entries—maybe RABBIT HOLE instead of RABBIT EARS, but that’s about it. And the order being the same isn’t a smoking gun. It was a 50/50 shot, since the longest entry, the 15-letter one, has to go across the center.

So what makes this puzzle suspicious? Look at the location of that first theme entry, RABBIT EARS. In 99 percent of crosswords with a 10-letter, 15-letter, 10-letter theme pattern, that top entry would start in the first column, flush to the left of the grid. Usually it would be in the third row, as it is here, but occasionally in the fourth row.

Starting it on the sixth column was a very odd decision for the Times’ constructor to make—and yet this odd decision was replicated in Parker’s version. This calls to mind those fake towns cartographers stick on their maps to see who’s copying their work. Coupled with the three repeated theme entries in the same order, this is the first of our examples where, in a vacuum, I would wonder whether the second constructor had swiped the theme from the first. I wouldn’t be sure, but I sure would wonder.

And making me wonder even more: The two grids’ black square patterns are yet again identical. Once is a coincidence; twice is a huge red flag, especially since this is a more unconventional grid pattern than the one in our previous example. There’s nothing particularly strange about seeing two crosswords with identical black square grid patterns. But combined with the other factors here, it’s getting harder to make the case that this is a coincidence.

Now, let’s bump it up to an 8 on the Suspicion Scale, at which point the excuses get very hard to believe.

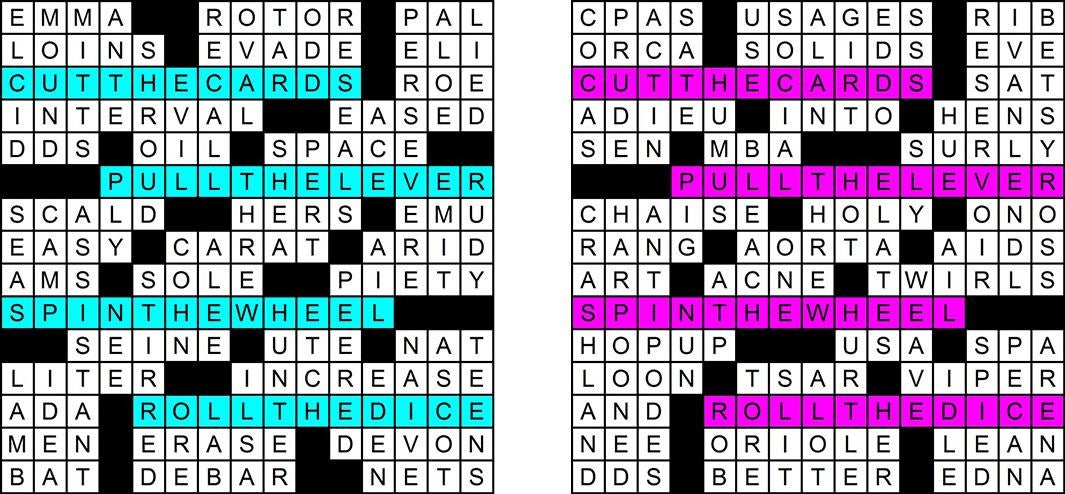

Image by Matt Gaffney

In the original NYT puzzle of Feb. 7, 2005 (on the left), the theme entries are CUT THE CARDS, PULL THE LEVER, SPIN THE WHEEL, and ROLL THE DICE. They’re clued as “Poker instruction,” “Slots instruction,” “Roulette instruction,” and “Craps instruction.”

In the Universal duplicate from 2009, the theme entries are the same, and placed in the grid in the same order. Only one of the clues is the same in the Universal puzzle, “Slots instruction.” The others: “Advice to a spendthrift?” for CUT THE CARDS; “Play a Merv Griffin creation” for SPIN THE WHEEL; and “Go for it, in a way” for ROLL THE DICE.

It is extremely odd that just one of the clues in the Universal puzzle—the one for SPIN THE WHEEL—is a gambling game instruction. It’s customary for a constructor to tip off his theme by alluding to it in the clue for every theme entry. Although it’s not 100 percent clear what happened here, the most plausible scenario is that the theme was borrowed from the NYT puzzle and then three of the four clues were changed. Those changes broke the theme, leaving the solver to think that Universal’s theme entries were just a semi-random set of four phrases—four phrases that just happened to appear as an NYT crossword theme a few years prior.

Another of Parker’s puzzles reflects the same mismatch between a theme and its clues. Here’s a bonus 8 on the Suspicion Scale:

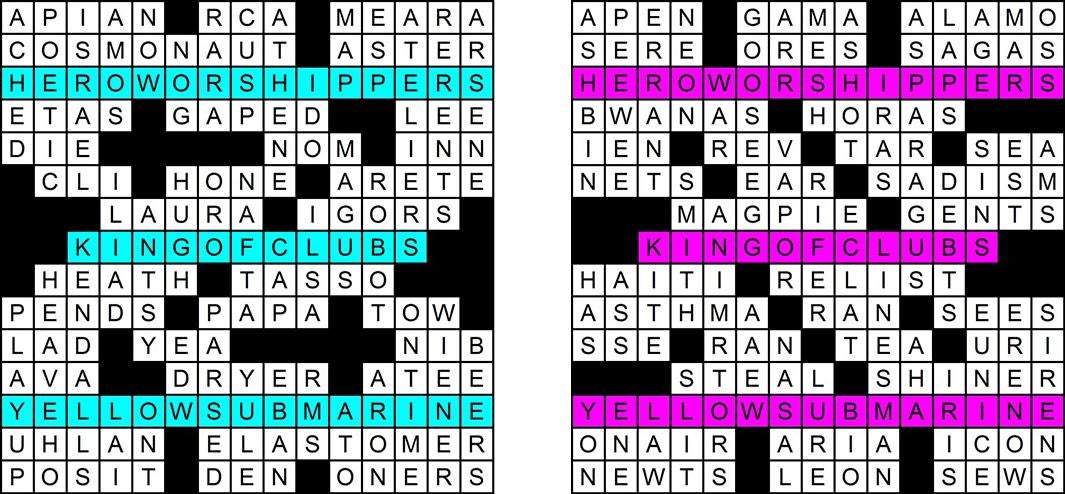

Image by Matt Gaffney

In the NYT original from 1994 (on the left), we have three sandwich-based puns: HERO WORSHIPPERS, KING OF CLUBS, and YELLOW SUBMARINE. In his 2007 version—same theme entries, same order, same grid placement—Parker keeps one of the sandwich puns and drops the other two. (He clues KING OF CLUBS as “Card fit for royalty?” and YELLOW SUBMARINE as “Top-10 tune of 1966.”) Again, this is not a logical set when you use only one sandwich pun. The fact that one of those sandwich puns remains in the 2007 puzzle is a clue about what’s going on here: It’s like a Law & Order episode where a suspect gives himself away by revealing a detail he couldn’t possibly have known unless he’d been at the scene of the crime.

Finally, let’s see what a 10 on the Suspicion Scale looks like.

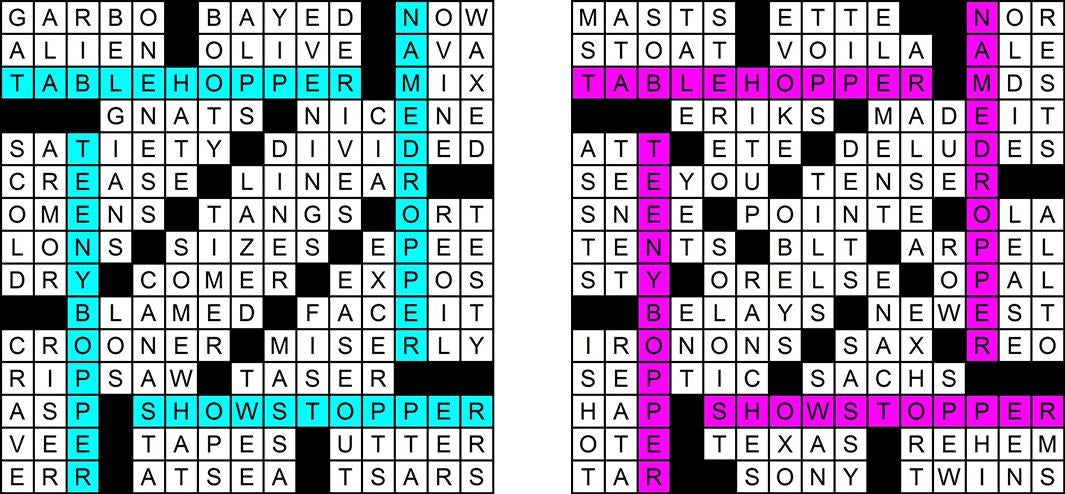

The NYT original, again on the left and published in 1997, features four theme entries in a pinwheel pattern. Starting in the upper-left, they are TABLE HOPPER, NAME DROPPER, SHOW STOPPER, and TEENY-BOPPER.

The Universal puzzle of 2006 features the four theme entries in the exact same locations as the NYT version. What makes this a special case is that three of the four theme clues are identical as well.

TABLE HOPPER is “Restaurant gadabout” in both puzzles, an odd clue to be sure, but one somehow chosen by both constructors. SHOWSTOPPER is “Dazzling performer” in both, while NAME DROPPER is “Egotistical conversationalist.” Needless to say there are many dozens of ways to clue these terms. The chance that three of the four would be identical is beyond infinitesimal.

In the crossword world, copying someone else’s themes is verboten. A theme is the soul of a crossword, what makes it unique. As Shortz pointed out in a recent interview on the plagiarism allegations against Parker, “It can take a puzzle maker as much time to come up with a good, fresh theme as to fill the grid and write the clues.”

The evidence suggests that Parker did in fact swipe themes, and did it repeatedly, over a long period of time. If USA Today and Universal come to the same conclusion, then they should treat this as plagiarism. No other word fits better in this particular puzzle.