In the 1980s, when Brian Sheppard created a computer program that played Scrabble, he typed in a lot of words—more than 100,000 of them, from the Official Scrabble Players Dictionary and Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. His program, Maven, revolutionized how expert players thought about and played Scrabble. (It also beat them.) Sheppard continued to update his software by hand until 1996, when a Scrabble player who helped assemble the third edition of the OSPD gave him the words via a digital file. Electronic word lists have circulated freely ever since.

These lists power the Internet Scrabble Club, a real-time playing room created by a Scrabbler in Romania. They also fuel study and analysis tools with names like Zyzzyva, Zarf, Quackle, and Elise. But the lists are samizdat—gray-market e-documents traded in the small but intense Scrabble community, which is filled with programmers and math brainiacs. Hasbro Inc., which owns the rights to the game in North America, and Merriam-Webster Inc., which publishes its official lexicons, have never publicly released the digital lists. At the same time, they have never attempted to control their spread—until now.

After two decades, Hasbro is cracking down on the dissemination and use of the word lists, and is seeking to license their use. Players are worried about the future of the programs, apps, and websites that are indispensable to the modern game, and they’re resentful that a multibillion-dollar corporation is hamstringing the developers who designed the Scrabble tools (for no pay) and distributed them (usually for free). The company’s action also raises an intriguing legal question: Can a list of words be copyrighted?

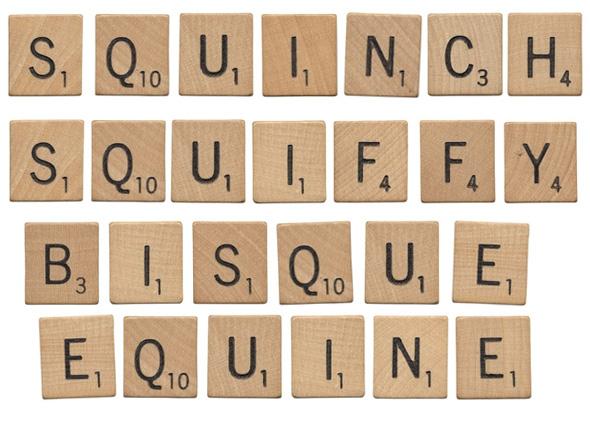

The lexical kerfuffle began over the summer, when Merriam-Webster published, to much publicity—selfie! hashtag! bromance!—a new, fifth edition of the OSPD. The book contains more than 100,000 words, including 5,000 new ones, of two through eight letters plus inflections. Purged of words labeled “offensive,” the OSPD includes definitions and parts of speech and is intended for home and school play. Separately, Merriam-Webster published a third edition of the Official Tournament and Club Word List. The OWL is sold only to members of the North American Scrabble Players Association, or NASPA; as its name suggests, it governs play in about 150 clubs and more than 300 tournaments a year in North America. The OWL is a straight alphabetical list—no definitions or other descriptive matter—of every word two through 15 letters long acceptable in competitive Scrabble, including the dirty ones, a total of nearly 188,000. It is the primary focus of the ongoing controversy.

While Merriam-Webster publishes both the OSPD and OWL, Hasbro claims the copyright on them. Like any dictionaries, the paper-and-ink books are rabbit holes for word lovers. But competitive Scrabble runs on digital sources. The program Zyzzyva, for instance, allows players to set parameters on words—like length or probability, meaning the likelihood of a word being plucked from a set of 100 tiles—and then solve anagrams one at a time. Players use Zyzzyva to learn and review words, and laptops loaded with the program adjudicate word challenges at tournaments.

Shortly before the National Scrabble Championship this August, Hasbro told NASPA that it had concerns about the revised word lists getting loose. It wanted to ensure that digital versions of the new OSPD and OWL were not freely downloadable from applications that contained them, as the current lists often have been. Hasbro said Zyzzyva was in violation of the company’s copyright.

Zyzzyva’s creator, Michael Thelen—who designed the program in 2005 as a personal study tool and then shared it with fellow players—was worried about getting sued. He also wanted to ensure that players had access to the new words. So he sold Zyzzyva to NASPA.

NASPA, which reported total revenue last year of $245,775, then negotiated with Hasbro, which reported revenue of more than $4 billion. One person involved in that negotiation said that Hasbro asked for a “significant” annual fee to license the use of the new word lists. The parties agreed on a smaller, one-time payment that will make the OWL and OSPD available through Zyzzyva to dues-paying NASPA members only, with coding tweaked to prevent the word lists from being extracted in large chunks. Hasbro’s vice president for gaming marketing, Jonathan Berkowitz, declined to comment on the payment. “There are all sorts of legal reasons to set up licensing arrangements the way we do,” he told me. Berkowitz added: “Our goal is not to monetize NASPA. Our goal is really about the democratization of this game and getting as many people this content as possible.”

Competitive Scrabblers see Hasbro’s action as restricting, not democratizing. No one disputes that the company is entitled to protect and control what it considers its intellectual property, especially against commercial challenges. But for decades, players, not Hasbro, created the physical and intellectual stuff—word lists, tournaments, ratings systems, study aides, equipment—that turned the company’s trademarked game, invented by an out-of-work architect in the 1930s, into a sophisticated and media-friendly subculture. (I wrote a book about it.) “We’ve done it as a labor of love,” César Del Solar, who developed the anagramming website Aerolith, told me. “We didn’t try to do this to make any profit. We did it to help ourselves get better and help other players get better, to have a community.”

A nonprofit managed by players and financed mostly by dues and participation fees from 2,300 members, NASPA is trying to keep that community together—without antagonizing its corporate overlord. The group has and wants to keep a license to use the word “Scrabble” in its name and activities, and it’s trying to rekindle Hasbro’s interest in bankrolling tournament play. (For almost two decades, Hasbro spent as much as $700,000 or $800,000 a year on competitive Scrabble but eliminated nearly all support for clubs and tournaments in 2008.) “As a result, this did not seem like a hill to die on,” a NASPA executive wrote on Facebook during a recent discussion of the word list and licensing plans.

Take out the lawyers-and-money imbalance between the two sides, though, and it would be a tempting hill to storm. While there’s no doubt that dictionaries are protected under U.S. copyright law, the copyrightability of a list of words isn’t as cut and dried.

Dictionaries enjoy copyright protection for two main reasons: Their creators make judgments about what words to include, and entries feature definitions and other original material. (Just last week, a federal court in Massachusetts ruled against a plaintiff who wanted to copy and repurpose the bulk of Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate, including definitions, for his own dictionary.) But in 1991, in Feist Publications Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., the Supreme Court decided that a phone company wasn’t entitled to a copyright on its white pages. That’s because the list of names and numbers lacked an important requirement: originality.

The definition-free OWL and a words-only version of the OSPD might be said to resemble the phone book. The facts in them—the individual words themselves—wouldn’t be considered “original” and likely couldn’t be copyrighted. But the lists might represent “an original selection or arrangement of facts,” as Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote in Feist. “These choices as to selection and arrangement, so long as they are made independently by the compiler and entail a minimal degree of creativity,” she wrote, “are sufficiently original that Congress may protect such compilations through the copyright laws.”

The fundamental question, then: Is a Scrabble word list minimally creative, or is its compilation as rote as a phone book?

Since the OSPD was first published in 1978, the creation of a set of official Scrabble words has been a collaboration between players and Merriam-Webster. The eight editions of the Scrabble books (the OWL was first published in 1996) have taken words from 14 sources: five printings of Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate plus nine editions of dictionaries from five other publishers—Funk & Wagnalls, American Heritage, Webster’s New World, Random House, and Oxford. Volunteers from the Scrabble community scour the dictionaries to identify words that meet the game’s rules and that are new to the game. Merriam-Webster lexicographers vet the words, write short definitions for the OSPD, and publish the books.

All of that takes thousands of hours of work. But work is irrelevant to copyright; Feist rejected what’s known as the sweat-of-the-brow doctrine. Instead, the legal question might center on whether the raw lists are “original” enough to justify protection—especially the definition-free OWL, which differs substantially from the OSPD. The rules for compilation are straightforward: words between two and 15 letters long; no proper names, hyphens, apostrophes, or abbreviations; no words considered foreign. “You can have a million interns working at a million typewriters to derive all of these words and go through every page of every dictionary,” says Aaron Williamson, an intellectual property lawyer with the firm Tor Ekeland P.C. in Brooklyn, New York. “If all they’ve done is say this one meets the Scrabble rules and this one doesn’t, they probably haven’t done enough to deserve a copyright.”

Hasbro disagrees. “We have a curated word list that is created for the purpose of playing the game and directly relates to playing the game. That’s copyrightable,” Berkowitz, the Hasbro executive, says. “From Hasbro’s perspective, the two are grouped together and we see them as one and the same.”

Even if a judge agreed with that line of argument, there are other reasons Hasbro might be in an awkward legal position if it went after a Scrabble tool for using the word lists. For one, a court might not look kindly on the fact that the lists were compiled using volunteer labor; Scrabble players aren’t paid for their work. Plus, Hasbro has almost never policed underground usage of the lists. (It did shut down the copycat game Scrabulous in 2008, not because of the words but because the game violated Hasbro’s board design and other trademarks.) The company hasn’t even been especially attentive in house. The official Scrabble app made by Hasbro licensee Electronic Arts lists Merriam-Webster, not Hasbro, as the copyright holder of the OSPD, and it doesn’t even mention the OWL, which the app seems to employ (dirty words are playable). The EA app also doesn’t acknowledge sources for Italian, German, and Portuguese word-list options.

Finally, Hasbro has never received permission from other dictionary publishers to use their words to compile the OSPD and OWL, nor has it credited them by name. But even if Hasbro were to argue that it legally borrowed only a small number of words from the non-Merriam-Webster dictionaries, Williamson said the company could face a “copyright misuse” problem: that is, suing for infringement of its own word lists when it’s making unlicensed use of word lists from other publishers.

Then there’s the question of whether the use of word lists by programs like Zyzzyva are covered by fair use. Three of the four fair-use criteria seem to tip against Hasbro. The use of the copyrighted material is for “nonprofit or educational purposes” (to help Scrabble players learn words, not to make money by selling a product); the material is highly factual (lists of words); and the use has little impact on the market for or value of the copyrighted work (people still buy the dead-tree OWL, Hasbro has been unconcerned by past use of the digital lists, and the company hasn’t entered the tiny market for advanced Scrabble study tools).

The fourth fair-use criterion—the “amount and substantiality of the portion used”—could be trickier. In Hasbro’s favor, it’s clear that Scrabble app-makers would need to borrow the entirety of the new OWL for their products to be useful. But developers could argue that Scrabblers only access small chunks of the lists at a time, and they could disable functions that allow users to download the words. (Zyzzyva is encrypting the word lists now.) That could make the facts of a Scrabble lawsuit similar to those in two recent cases, Google Books and TVEyes, in which courts ruled in favor of defendants who created huge databases of material—books in the first case, TV and radio broadcasts in the second—but made only small portions available to users at any one time.*

For now, these are all academic questions, because Scrabble programmers seem disinclined to challenge deep-pocketed Hasbro. “To be honest, I am not interested in any kind of legal battle,” says Gordon Dow, the creator of the free word-lookup app Zarf. “Any legal complications might certainly dissuade me from updating,” says Mick West, who designed a similar app, CheckWord, which offers free and 99-cent versions. Del Solar, the Aerolith website programmer, says, “If Hasbro comes after me, I’d have to take down the site.”

Meanwhile, Scrabble techies have created a renegade digital version of the new OWL by performing optical character recognition on the physical book, though it isn’t circulating on the Web. (Not yet, anyway. “WikiLeaks, anyone?” one player told me.) Introduction of the updated OWL was scheduled for Dec. 1 but has been delayed while Zyzzyva gets reprogrammed and NASPA figures out what to do about the other apps.

There’s a simple solution that wouldn’t stifle the creation of the next cool Scrabble tool and would give players access to the words on whatever platform they like. Hasbro could let developers use the lists upon request, at no charge but with a requirement to post a copyright notice. That’s what HarperCollins, which publishes the word list that governs English-language play outside North America (and is gaining traction at tournaments here), has done with programs including Zyzzyva. If someone tried to monetize an application that employed the lists without permission, well, that’s why companies have lawyers.

And if Hasbro liked a Scrabble app that bubbled up from such a modified open-source culture, it could reward innovation. That’s how the company made its official Scrabble CD-ROM in the late 1990s. It bought Brian Sheppard’s Maven.

*Correction, Sept. 30, 2014: Due to a production error, this piece originally misstated that the TVEyes case was heard by a federal appeals court. It was ruled on by the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. (Return.)