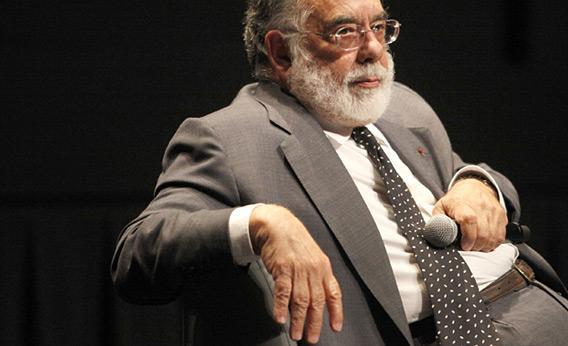

“Opening a hotel,” says Francis Ford Coppola, “is a lot like shooting a movie.”

We are sitting in the ground-floor bar of Palazzo Margherita, which opened last Thursday in Bernalda, the small hill town in Basilicata, Italy, from which Coppola’s grandfather, Agostino, emigrated to New York in 1904.

“A film needs a big idea. After that it’s a matter of incredible attention to detail,” he explains. “Here the concept is a 19th-century palazzo with a patina of age. But then there are a million details to get right if it’s to work as a 21st-century hotel. In a movie, the details are the things an audience will notice. In a hotel it’s everything the guests experience.”

Palazzo Margherita has been in production for six years, longer than it took to make Apocalypse Now, and Coppola has been closely involved at every stage. “I like to make decisions,” he says, and goes on to describe choosing everything from china and cutlery to what will be in the mini-bars. “I am not just a person who licenses his name.” But then he’s been thinking about Bernalda since childhood, having grown up with stories of this “mythical” place. “‘Bernalda bella’, my grandfather called it. We believed it must be like Brigadoon or something.”

A week before opening, however, he’s preoccupied with practicalities. Over lunch he had given the kitchen staff “notes” on how a “New York mafia dish” of chicken, mushrooms and rustic Italian sausage might be improved. It needed rosemary, maybe some oregano and the addition of little artichokes. The salsiccia secca should be sliced more thinly. And it should be served sizzling on a cast-iron platter, not in a terracotta dish. Later, our conversation is interrupted by the delivery of a sample shower door: the etching of the hotel’s monogram needs refining, he thinks, so back it goes.

For Coppola likes to get things right. It’s an abiding regret, he mentions as an aside, that the paterfamilias in the first two parts of The Godfather is addressed as Don Corleone, when correctly he should have been Don Vito (“don”, like “sir”, precedes a first name). Fortunately Dean Tavoularis, the Oscar-winning production designer who first worked with Coppola in 1972, is on hand to advise on issues such as the positioning of shaving mirrors in the bathrooms. “Dean”, says Coppola deliberately, “has a very good eye.”

Palazzo Margherita is Coppola’s fifth and most obviously luxurious hotel. The first, Blancaneaux Lodge, a jungle retreat in Belize, opened in 1993, after 11 years as a family holiday home. It was followed by Turtle Inn, again in Belize, on the coast, and La Lancha in neighbouring Guatemala. I have stayed at all of them and still consider them among the loveliest places I know: simple (no phones, no TVs, no air conditioning), rustic, sensitive to their wilderness settings and decorated in impeccable taste. In 2009 he also opened a six-room townhouse, Jardin Escondido, in Buenos Aires.

In contrast, this one feels appropriately like a palace. Its splendid new interiors are the work of Jacques Grange, whose last hotel was the recently revamped Mark in New York, and subtly recall the great baroque palaces of the Castelli Romani near Rome, with exquisite new wall paintings, original frescoes, chandeliers, specially designed tiles and marmorino, a kind of stucco made from powdered marble, buffed to look like the real thing.

It’s a far cry from the humble village home Coppola stayed in when he first came here in 1962, soon after graduating from the film school at UCLA. He’d just won the Samuel Goldwyn Writing Award and “from being totally a pauper”, he suddenly had $2,600 as well as a job as a soundman on a movie Roger Corman was shooting in Europe. “So of course I bought a brand-new Alfa Romeo Giulietta Spider to be picked up at the factory in Milano. When we finished the movie, I took a ferry to Brindisi and drove my nifty sports car to Bernalda.”

There he found his grandfather’s first cousin and many other relatives – today he reckons perhaps a quarter of the town’s 12,000 population are relations at some remove or other (another cousin, Donato Coppola, is renovating the palazzo next door) – and so began half a century’s association with the place.

“After I made The Godfather,” he continues, “I became very famous in Italy and Bernalda made me an honorary citizen. There was a whole festa to honour me.” But he never, he insists, felt he wanted a home there, certainly not a dilapidated palazzo. In 2005, however, Bianca Margherita, the octogenarian granddaughter of the olive-oil magnate who’d built the property, asked if he’d like to buy it. “She figured I was a sucker.”

His instinct was to decline, but then the actor Michele Russo, also a native of the town, whom Coppola had given a part in The Godfather III, alerted him to Law 488, a government initiative to encourage development in the south by offering substantial subsidy to projects such as hotels. “We worked up the plans to apply for it, were ruled eligible and went for it. But of course the project turned into something much bigger and complicated than I imagined. They wouldn’t let me put a swimming pool in the garden, because it’s listed, so I had to buy another piece of land for that … ” Walls had to be reconfigured, vaulted ceilings reinforced, doorways relocated. Every original floor tile was raised, numbered, renovated and then replaced over underfloor heating. But the promised subsidy remained elusive. He is audibly bitter that he’s never seen a cent of it: “I still feel the Italian government owes me because I played by the rules.”

Whatever the torments of its creation, the resulting hotel is a triumph: a beautiful one-off that feels more like a home than a hotel. There’s not even a sign on its ornate façade: just a house number (64), a buzzer and a modest doorway cut into a tall wooden gate. Step through it and you find yourself in an elegant courtyard, which in turn leads through a balustraded arcade into a luxuriant exotic garden, cross-hatched by brick paths and shaded by palm, pine, olive, fig and citrus trees.

The hotel has just nine rooms, six in the palazzo and three in former stables on the southern edge of the garden. There isn’t a restaurant in the conventional sense. Rather there’s a huge table that seats 12 in the brick-vaulted kitchen, where two local women, Filomena and Enza, produce delicious, unfussy meals of a kind you might be offered in someone’s home: antipasti, hearty soups, pasta, meat or fish preceded in the Italian style by a plate of local vegetables and, finally, homemade pastries filled with custard or whipped ricotta.

If the communal table seems too close to the pizza oven, those who’d rather dine privately can do so anywhere in the courtyard, the garden, the grand salone (which doubles as a screening room), their bedroom, their terrace (assuming they’re in rooms 9 or 4, those favoured, respectively, by Coppola and his film-director daughter Sofia, hence high-season rates in four figures). There are also two bars: an intimate upstairs one for guests and another public space with its own street entrance, a pizza menu and walls hung with monochrome photographs of actors and filmmakers who have worked at the Cinecittà studios in Rome.

Self-effacingly, there’s no portrait of Coppola among them. Nor do any of the 30-plus films he’s directed feature in the extensive library of classic Italian or Italy-set movies loaded on to the television in each room. You will, though, find wines from his Californian vineyards on the winelist, along with wines grown locally in Basilicata and Puglia and from Château Thuerry in Provence, which belongs to Sofia’s father-in-law.

There isn’t a spa or gym (though there are bikes), but the sweeping sands of the Ionian coast lie less than 10 miles away and the hotel has rights to open its own beach club on an as-yet undeveloped stretch, to which it will run a shuttle. In the meantime, they recommend the beach at Riva dei Ginepri.

There’s another lido near Metaponto, a 20-minute drive away, site of the ancient Greek colony, founded about 600BC, where Pythagoras hit on his theorem and now home to a museum of antiquities.

Bernalda itself is less obviously an attraction, for in the century or so since Agostino Coppola judged it “bella” it has rather lost its looks. But it’s not without appeal. There is a squat 15th-century Aragonese castle and a couple of handsome churches. Coppola calls it “the real Italy, authentic Italy – Italy as it was”, praising its restaurants, its festas, its languorous way of life. “Far from the traffic of men,” was how Carlo Levi described this wild, remote area in Christ Stopped at Eboli, his memoir of a year spent in exile in a village 25 miles from Bernalda in 1935. Outwardly it may seem a closed society, “another world which no one can enter without a magic key”, as Levi observed. But such is the celebrity, the popularity, of Don Francis that guests at his palazzo may feel they too have been handed the keys to the town.

This article originally appeared in Financial Times. Click here to read more coverage from the Weekend FT.