Civil rights had a bridge in Selma, Alabama, and gay rights had a bar in Greenwich Village. Last week, foodies made their stand at a former Rockefeller family dairy in New York’s tony Westchester County. A group of more than 200 food activists, peppered with a few dozen conventional farmers, ranchers, and retailers, gathered at the Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture for a meeting organized by the New York Times to discuss the future of food. Their goal was to transform a trend into a full-fledged social and political movement.

“There is a war here!” thundered Mark Bittman, the New York Times columnist and self-described rabble-rouser, to scattered applause in the conference’s opening speech. “I won’t apologize for not being genteel.” Much of what the current food system produces, he charged, “pollutes, sickens, exploits, and robs.” There were no paddy wagons or billy clubs, however, and gentility quickly returned by supper. A few ranchers muttered unhappily about Bittman’s declaration of war, but all sat down together in the center’s upscale restaurant to enjoy carrot cutlet and rotation risotto as heritage turkeys gobbled in an adjacent pasture.

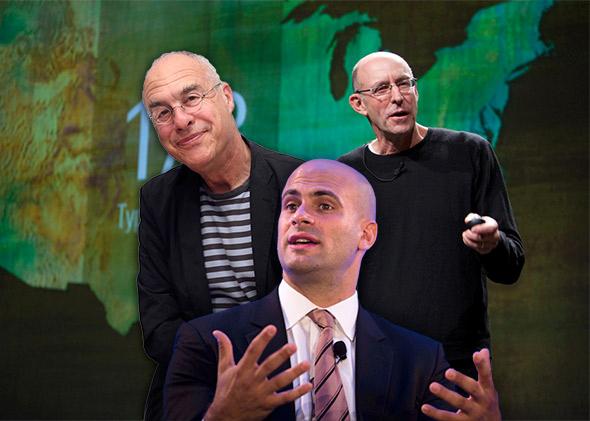

At the moment, the food movement is, at best, in an awkward and confused adolescence. It doesn’t really know what it wants, how to behave, or whom to trust. There is a hodgepodge of individuals and organizations concerned about the safety of their food, the treatment of livestock, the accessibility of organic vegetables, the rise of diabetes, the low pay of food workers, the health of soil, and the role of farming in climate change. “They are not always the same people,” Michael Pollan, the famed author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, told me. While foodies have enjoyed scattered political successes—the nation’s first soda tax was passed in Berkeley, California, on Nov. 4, and a few states have recently approved food charters—the groups behind these successes have yet to coalesce into a single political bloc.

Pollan and Bittman want to herd these cats toward common objectives in order to change a food system that they see as a deadly threat to U.S. national security. On Nov. 7, just a few days before the conference began, Bittman, Pollan, and two co-authors published a Washington Post opinion piece called “How a national food policy could save millions of American lives.” The manifesto has something for everyone: It demands a fair wage for food industry workers, well-treated animals, limits on marketing junk food to kids, and access to healthy food free of toxins for all Americans, as well as support for food policies that jibe with public health and environmental goals. In the essay, they challenge the Obama administration to join them on the right side of history by taking a stronger stand in remaking a system that they contend is controlled by “agribusiness oligopolies” uninterested in the public welfare.

Bittman, Pollan, and one of their co-authors arrived at the Stone Barns conference eager to spread their message. For a movement often accused of elitism, the setting seemed a bold choice. Once part of a sprawling Rockefeller estate, the center comprises a bucolic farm designed to train a young generation of organic farmers and a restaurant where acclaimed chef Dan Barber serves a $198 tasting menu. Participants paid $1,400 apiece to attend the day-and-a-half meeting sponsored in part by Porsche—one of the perks, along with the carrot cutlet and a pig-butchering demo, was the chance to schedule a test drive. “So what—we all meet in a Marriott?” said a testy Bittman when I asked him about the luxury of our surroundings.

Though the backdrop was upscale, Pollan and Bittman came to Stone Barns to prepare to take their argument to the streets—and to Washington. “We’ve tended not to think of food as a public concern,” Pollan told me. “But if there were a food bill, the public would feel they have a stake, and you would have urban legislators suddenly wanting to be on a Food Committee, because they represent eaters.” Pollan and his colleagues intend to canvass Capitol Hill for support, and their manifesto already has garnered 18,000 signatures of support that the Union of Concerned Scientists has forwarded to the White House. If the Republican Congress ignores them, “it is something that Obama can do unilaterally.”

There’s one main problem with that plan, though, and it became abundantly clear at the Stone Barns conference: The White House hasn’t yet shown any support for Pollan and Bittman’s food policy proposal. “We already have a food policy,” insisted Sam Kass, the executive director of Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move program and the senior policy adviser for nutrition policy. At the conference, Kass trumpeted the food-related successes of the administration, like making school lunches healthier and keeping junk food out of school vending machines. But he also pointedly warned that it is “a political liability” to criticize incremental changes and demand only sweeping revisions of the food system, a veiled reference to the manifesto. The way to be a better food policy, he argued, is through immigration reform—a key issue for farmers and many of their workers—as well as an increase in minimum wage that would benefit fast-food employees. In other words, Kass thinks that food activists can improve the food system by supporting traditional progressive labor goals.

However, Kass did concede that bringing health care concerns into the food debate has “massive untapped potential.” Limiting the junk food market and advertising aimed at hooking children into sugary products is something that could energize insurance companies, the medical profession, and other communities to exert political pressure on the existing system, in which there are few limits. That struggle is already quietly taking place as the federal government assembles its 2015 dietary guidelines; the 2020 guidelines will include a mandated section on the diet of young children likely to prove controversial. Research shows that food habits instilled in the first two years are enormously important for a person’s future health, says Marion Nestle, a New York University nutritionist, who spoke at the meeting.

Clearly, Kass shares Pollan and Bittman’s explicit goals, even if he disagrees with the best way to meet them. But there’s another obstacle standing in the way of the proposed national food policy: the people who actually grow our food. All the talk about the evils of the food industry clearly baffled and shocked the few actual food producers at the Stone Barns conference, including members of the U.S. Farmers & Ranchers Alliance, an organization based in Missouri that sponsored a panel to get its voice in the mix. The cultural gap between the New York and California foodies dominating the meeting and the Midwestern producers yawned wide. “We’re the Big Ag you were taught to hate,” Illinois pig farmer and businesswoman Julie Maschhoff, who was on the panel, told the audience. “I grew up on a corporate farm, and my grandfather had a corporate farm before it was bad.” She spoke of her excitement that biotechnology will “create a better animal on fewer resources” and noted something that would be unremarkable to most urban foodies: “One of my good friends is a vegetarian.”

On the same panel, Joan Ruskamp, a cattle feeder in Dodge, Nebraska, expressed dismay at the direction of the conversation started by Pollan and Bittman. Ruskamp told the group: “Please let us be involved in the conversation about food!” She added, “I don’t want it to be a war.” Ruskamp went on to refer to cattle as “one of the great converters of grain to protein” and organic meat as a “niche marketing tool,” and to defend antibiotics as necessary to relieve animal suffering. Both Maschhoff and Ruskamp later said they were appalled by Bittman’s acerbic language. “I felt deliberately offended,” said Ruskamp.

By meeting’s end, Bittman had backed off his revolutionary rhetoric. “We’ve learned that everyone wants to be sustainable, to produce less waste and better food, avoid worsening climate change, use fewer antibiotics, encourage more people to farm, and encourage more people to farm smarter,” he said. “We all want the same thing.” Life, he said, is compromise, and he insisted “the food movement is not about targeting individual farmers,” but about changing the entire system. He added that he thought that the food movement could build bridges between different camps. “This is not about being adversarial,” Bittman added. “We are a family. It is our food system. Let’s make it as good as we can for everyone.” Ruskamp was satisfied. “The tone changed,” she said. “It softened. Perhaps being here made the difference.”

Pollan acknowledges that the food movement has a long way to go. “We’re still young, and we don’t have a big membership organization,” he told me. Tom Colicchio, a high-end chef and sustainable food advocate who was at the conference, agrees that the food movement—whatever its goals may be—needs broader support before it’s ready for prime time. “To me, food has always been political,” he told me. “Now the mission is to raise public consciousness around food.” He added that this is a time to focus on the movement’s grass roots. “I don’t think we’re on the bridge to Selma yet.”