The Urban Agriculture Conference’s Manhattan farm tour—as in the central borough of New York City, not Manhattan, Kan.—called into question everything I knew about farming. And as a former farm kid, I know a little something about farming. I know, for example, that my family’s Indiana cornfields look nothing like the rooftop of the Waldorf Astoria.

Vegetables growing on the roof of a luxury hotel on Park Avenue are a potent symbol of the popular appeal of urban agriculture. But the inclusion of the Waldorf Astoria on a farm tour demonstrates just how far the term farm is being stretched these days. As I stood among the bees, herbs, and vegetables overlooking the terrace of the suite where Marilyn Monroe stayed, I exchanged glances with the New England farmer next to me, and we agreed: The rooftop garden was sublime, but it was not a farm.

What’s the difference between a garden and a farm? The popularity of small-scale sustainable agriculture, particularly in an urban setting, has blurred the line between the two. Even agricultural experts can get confused. In December, U.S. Department of Agriculture Deputy Secretary Krysta Harden told a conference of young farmers at Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture in Pocantico Hills, N.Y., that she knows diversified growers sometimes hear from their local Farm Service Agency representatives that they are not farmers. Officials don’t always know what to make of those who grow small quantities of three-dozen crops instead of huge quantities of just one thing.

Confronting an assortment of plants on an acre of land, many Midwestern farmers I know would also call that a garden. Size matters, it seems. Yet size lies in the eye of the beholder. At the Black Farmers and Urban Gardeners Conference in November, a community gardener from Brooklyn, N.Y., insisted to me that something so large as an acre could only be a farm.

Convention holds that a farm requires a tractor or the presence of animals. But such distinctions fail when chickens and goats live in a community garden or when a 1,000-acre family grain farm has nary an animal in sight. Some people will say that location matters, that if it’s in a backyard, it must be a garden—just don’t tell that to Wally Satzewich and Gail Vandersteen, who sold their rural farm after realizing they could make more money growing in an urban setting. They describe their business, called Wally’s Urban Market Garden, as a “multi-locational sub-acre urban farm.”

Unspoken hierarchies of class, gender, and race are at play in the definitions, too. To call someone’s farm a garden (with its feminized connotation), a hobby farm (with its elitist connotation), or subsistence farm (with its impoverished one) can carry a whiff of superiority.

Out of this morass of stereotypes, a useful distinction emerges: A garden produces food for private use, whereas a farm produces food (or flowers or fiber) for others. This idea gets closest to how the USDA defines a farm: “any place from which $1,000 or more of agricultural products were produced and sold” in a given year. The only definition that matters to a farmer who wants to qualify for a federal grant, loan, or subsidy, it nevertheless surprises many people, since it means that a container planted with herbs counts as a farm if those herbs happen to be sold for $1,000 a year.

The Waldorf Astoria certainly produces a quantity of food worth more than $1,000. That the hotel uses the products itself rather than selling them at the nearest farmers market is a mere technicality.

A quarter-acre lot full of milk crates seems as unlikely a location for a farm as the roof of a hotel. But that is where Zach Pickens, the full-time farmer at Tom Colicchio and Sisha Ortúzar’s Riverpark restaurant on Manhattan’s east side, grows produce—and the space happens to be the same size as his grandparents’ garden in Ohio, where Pickens first learned to grow plants.

Does Riverpark, the second stop on the Manhattan farm tour, meet the USDA threshold? “Oh, I’ve got that,” Pickens says, explaining that the farm, which grows exclusively for the restaurant, tracks what it provides using prices equivalent to what it would pay to specialty purveyors or at local markets—where microgreens, for example, can sell for upward of $125 per pound. To Pickens the difference between farming and gardening is clear. In farming, he says, “You’re practicing agriculture in order to make money.”

That act of making money—not just producing, but selling—determines the difference between gardening and farming, for the USDA and most farmers, too. Even those who farm with the primary goal of improving the environment or building community believe that a financially robust enterprise is fundamental to the mission. As Richard Wiswall, author of The Organic Farmer’s Business Handbook, argues, true sustainability includes making a profit. At Riverpark Farm, says Pickens, “We want urban agriculture to be successful. We want people to see this and say it makes sense from a production and an economic standpoint.”

But not all places called farms make money. Does that mean they aren’t the real thing?

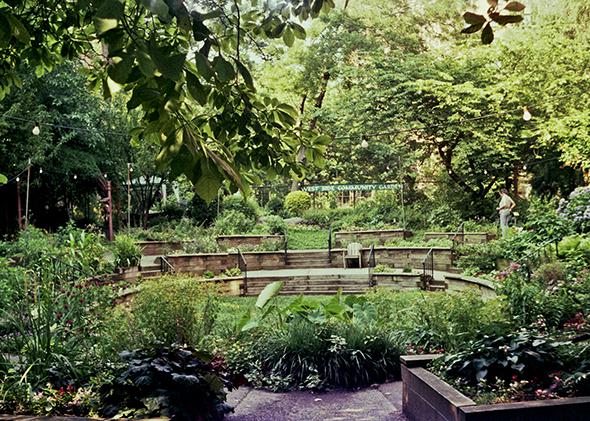

On a visit to New Roots Community Farm in the Bronx, N.Y., it certainly appeared that way to a fortysomething aspiring farmer from New Jersey who took one look at the half-acre site and said: “This sure doesn’t look like a farm.” With a few small beds for individuals to use as they wish, it looked just like a community garden. But according to program manager Kathleen McTigue, New Roots has a mission different from a traditional mission of community gardens, such as improving neighborhood aesthetics or providing space for public activities. “The goal really is to use it as a training site for food production,” she said. The farm is a program of the International Rescue Committee; its purpose is to help resettled refugees translate their agrarian backgrounds into job skills while addressing food-security issues in the neighborhoods in which they now live.

New York City Housing Authority, which runs all public housing in the city, has similar aims. Last year, in partnership with the nonprofits Added Value and Green City Force, NYCHA (which already has more than 600 community gardens for its residents) opened the first “large-scale urban farm” on its property, at the Red Hook West housing development. In these examples and others, activists and organizers want to grow food and set up markets in the service of providing greater access to healthy produce, improving education and health, conducting job training, and eradicating poverty.

They want, in short, to change America’s food system. And to do so, many choose the word farm over garden because of its connotations. As Ian Marvy, co-founder and executive director of Added Value, says: “It’s the metaphor to explore issues of sustainability, scope, scale, financial concentration, community control, equity, environmental degradation, global warming.” (It also doesn’t hurt that “It’s more cool to call it a farm than an educational garden,” says Pickens, who interned on an Added Value farm.)

Naming is an act of power. Calling the vegetables growing in a fancy hotel or in a private windowsill a farm rather than a garden may sound crazy, but that may be the point. The marketing potential of the word farm is significant—having a farm attached to one’s business can raise its profile as well as its profits. But for many growers, calling their site of production a farm, no matter how small, no matter what form that production takes, no matter whether they sell at a profit or give food away for free, is much more than good business or smart branding. It’s a deliberate attempt to change public perception, policy, and the paradigm of food production.

Agriculture must expand, many farmers, activists, and policy experts agree, if the planet is to feed its growing population while confronting climate change. At the USDA, Deputy Secretary Harden told me by email, “[W]e are excited about what the next generation of farmers is bringing to the table. Never before in the history of American agriculture have we seen so many different types of farmers.” As agriculture starts to look more like Riverpark restaurant and the farms in New York City’s public housing, that needed expansion is well underway.

At Red Hook West Urban Farm, when someone says, “Let’s go over to the garden,” Marvy gently corrects them. “Yeah,” he says, “let’s get over to the farm.” He will not need to correct me. But, given where I come from, I must draw the line at Park Avenue: I don’t think I’ll ever be able to call the Waldorf Astoria a farm.