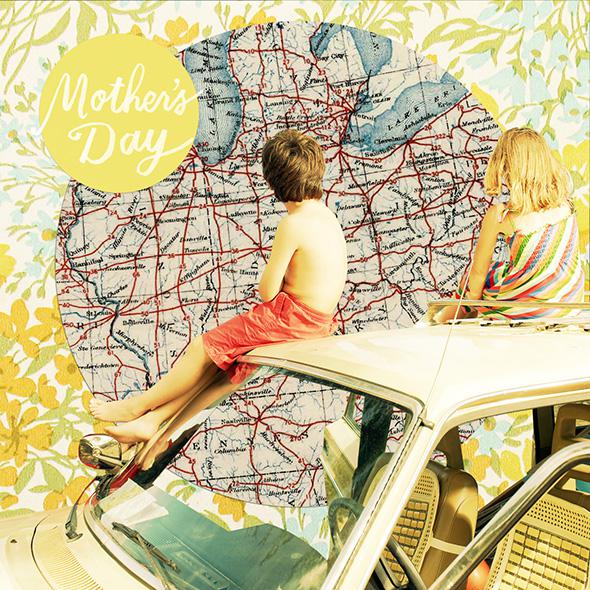

Nestled into our beanbags in the back of the family station wagon, my brother and I were oblivious to our surroundings. My mom had been driving for a while when one of us finally asked where we were going.

“I don’t know,” my mom answered.

A couple of minutes later, we asked again. Same answer.

Not having an actual destination intrigued us. Mom didn’t have a plan. “Could parents do that?” we wondered.

Far from anything familiar, my mom exited the highway. At the first traffic intersection, she looked at my brother, “John, right, left, or straight?” she asked. He answered. She asked me the same question at the next intersection. She drove on with my brother and me taking turns picking a direction at every stop. We wound up in Woodstock, Illinois, 30 miles from our home in Libertyville. We did three laps around the town, each time picking different directions but inevitably winding up at the same stop sign. The incessant arguing and complaining coming from the backseat at the start of the trip turned to laughter.

We asked my mom if she knew where she was.

“We’re lost,” she said.

“Cool,” my brother and I thought.

My mom had left our house without a destination in mind. She came up with the idea to get lost while driving. As a single parent, she was responsible for every decision, every day, and on that day, she’d had enough. She figured if she flipped the familial power structure on its head, she’d get a break. It worked. Plus, it had the added bonus of jolting my brother and me out of our comfortable roles of arch-nemeses, uniting us in a quest to get our mom lost. We got home late that night, which, of course, made the experience even better.

We played Let’s Get Lost again and again, and as we grew, it evolved. Our trips morphed into kid-planned getaways. My mom gave us a budget and a time frame. Heading out for spring break, she might say, “We have $600 and can go somewhere within an eight-hour drive of the house.” My brother and I would pore over maps. We learned to look for the little red numbers that told us the mileage. We learned how to calculate travel times based on the distance and type of road: fast on fat lines, slower on skinny lines. Sometimes, we would stretch a game of Let’s Get Lost into a couple of nights with no endpoint in mind. Once we spent half our budgeted amount, my mom would try to find her way home. Other times, we picked specific destinations and took turns acting as the navigator. Over the years, carefully planned trips combined with spontaneous ones meant we wound up in places as random as Clinton, Iowa, where we ate dinner from the hotel vending machines, and as beautiful as Mackinac Island, which turned into an annual destination and a place I look forward to taking my daughter.

At the outset of a trip, we would divide the total budget into daily amounts. Each morning, my mom would give my brother or me the daily amount in cash. The kid with the money was responsible for all decisions and expenses for the day. While we alternated days of responsibility, we usually wound up working together, something that rarely happened at home. At the end of the trip, my mom let us split any money we had left, which fostered our cooperation and led us to scrutinize all financial transactions. We double-checked totals on restaurant bills at the table and counted all change given back.

Once, a clerk at a convenience store short-changed my brother, insisting that John had given her a $10 bill rather than a $20. Leaving the store, my brother slumped into the backseat and quietly studied the stack of $20 bills that remained. A few minutes later, he said, “Mom, go back. I can prove I’m right.” He’d realized that the bills the bank gave us were new, with serial numbers in numeric order. When we’d returned to the store, my mom asked to speak to the manager after observing the clerk’s scowl as we approached the register. My 9-year-old brother told the manager the serial number of the $20 bill in the register. With no apology and a look to match that of his employee, the manager thrust a $10 bill toward my mom. My brother took it from his hand and we walked out.

We investigated lodging options with similar diligence. Arriving in a town for the night, we’d comb through the AAA guidebook and have my mom drive to all our top hotel prospects. My brother and I would get out and evaluate the rate based on the available amenities—mostly the pool, and the proximity of the rooms to the pool.

We messed up. We made decisions we regretted. Most notably the night we opted for an expensive room with a waterbed, which I realize now was in an establishment that very likely rented rooms by the hour. The waterbed got old after a few minutes, despite the quarter machine next to the bed that made it “sway,” and there wasn’t even a pool, which, in retrospect, was probably a good thing. The next day—our first day visiting Mackinac Island—we realized that because of the previous night’s splurge, we would have to start home that evening, rather than staying another night. My brother and I spent the rest of the day going through trash cans, collecting recyclables and turning them in for cash. We made back a fair amount of the previous night’s overage, and my mom helped out with the rest.

Reflecting on these trips now, my mom says she didn’t have any grand intentions. She didn’t set out to teach us about fiscal discipline, navigation, or cooperation. Mostly she was just sick of planning things, especially since my brother and I complained regardless of what she planned. However, just as the trips excited my brother and me, my mom remembers them being fascinating to her as well. We visited places she would have never chosen on her own, and she gained a new understanding of my brother and me by observing our decisions and decision-making processes. Also, she says that she trusted us, and handing over money and control of our schedule was a concrete means to demonstrate trust. As parents, our kids remind us again and again that our actions carry far more weight than our words. Our Let’s Get Lost and kid-planned vacations ended once we entered high school, when extracurriculars combined with our need for independence squashed the idea of family road trips. But the trust and respect, forged through hours spent together lost on some Midwestern backroads, remained.

My daughter is 5 now. She’s been on countless road trips in her life. And while I’m not quite ready to give her a day’s travel budget in cash and embrace vending-machine food as a meal, we did drop by a bookstore on our most recent trip and bought her her first atlas. And someday soon, we’ll load into our station wagon and she’ll take her parents somewhere we’ve never been. We’ll see what we find when we’re lost.