Not too long ago, shortly before our son turned 18 months old, an important document arrived in the mail. It was a revised birth certificate, reflecting our son’s new first name—Lev.

When Lev was born, we named him Liev—a name that autocorrect doesn’t think exists. But over the first five weeks of his life, my husband Dan and I realized we’d gotten his name wrong, and now we were issuing a very public correction over a single letter.

We hadn’t taken the naming process lightly. The artisanal baby name trend has prompted a sort of arms race for obscurity. Like many people, we wanted a name that was at once classic and unusual, so I went all Nate Silver on the stats, consulting the demographic trends state by state, just as I had with my daughter four years before. (Back then, trying to see around corners, I nixed one contender because it was trending in Maine, which seemed like a bellwether state.) But we couldn’t come up with a name that fit our son the way the name Olive fit our daughter—enveloping her right away when she was born, like a soft sweater.

Instead, we abandoned name after name—Arley, Gabriel, Jules—and were left with nothing. At some point my husband suggested Lev, a Ukrainian name meaning lion. In Ukrainian history, there was an important Lev who was the son of a Danylo who was the son of a Roman, and my husband—a Danylo who’s the son of a Roman—liked the historical parallel, and the link to his heritage. I liked the fact that Lev means heart in Hebrew. The only thing I didn’t like was the way the name sounded. That single syllable seemed hard and abrupt, like the rest of the syllables had been cut off by a slammed door. I argued for the Russian-style variant, Liev, which was softer. The more I said the name, the prettier it sounded, and my husband acceded, with reservations, since I argued so passionately for it. Also, we were running out of time.

And then the boy was born, and for reasons I can’t entirely articulate, his name didn’t work. Sometimes, when you’re house-hunting, you can walk into a bright side-hall colonial you coveted on Zillow, and you can’t imagine living there. Names are like that, too—you have to walk around in them, say them out loud to a sleeping child in the middle of the night. They say kids grow into their names, but sometimes they don’t. And then you have to decide what to do. From talking to other parents and reading about other people’s experiences, I’ve learned that some parents make peace with their choice, while others just start calling their kid something else, because the legal process is such a pain. But I couldn’t unfeel my regret once I‘d admitted it to myself, and I imagined decades of explanations in classrooms and doctors’ offices if we didn’t formally alter the name.

When the baby was 5 weeks old, we took him on a walk into town, and I told Dan I thought he’d been right all along. The kid seemed like a Lev. He had gray eyes, a huge forehead, and a dimple on one side. He was quiet and slept with his arms up in those ridiculous infant chicken wings. He looked, somehow, like he could handle something monosyllabic, a name with simplicity and directness and the beautiful circularity of my husband’s family history besides. Dan said he was a little surprised, but maybe because he’d long known he was right, or because he’d noticed I’d been omitting our kid’s name in favor of “the baby,” he also said he’d had a feeling. We pushed the stroller through town discussing how right this felt, and how awkward it would be to announce our son’s name again.

In fact, telling people turned out to be the easy part. Our 4-year-old wailed about it—the change unmoored her, as if we were trading Lev in for another kid—but friends and family were polite and supportive. (Perhaps because it’s no more acceptable to criticize someone’s second choice of a name than it is to question their original. Or maybe because the removal of a single letter seemed more like house-cleaning than a change.) My dentist told me he changed his son’s name in the hospital, walking up to the nurse’s station and asking them to give back the birth form he’d already filled out. Still, I knew that going through the legal process was unusual and kind of radical. Our mistake, I surmised, wasn’t in changing our minds, but in the timing. You can vacillate while you’re walking the hospital halls, waiting for your water to break, but once the kid arrives, the name defines him. You’re supposed to be certain.

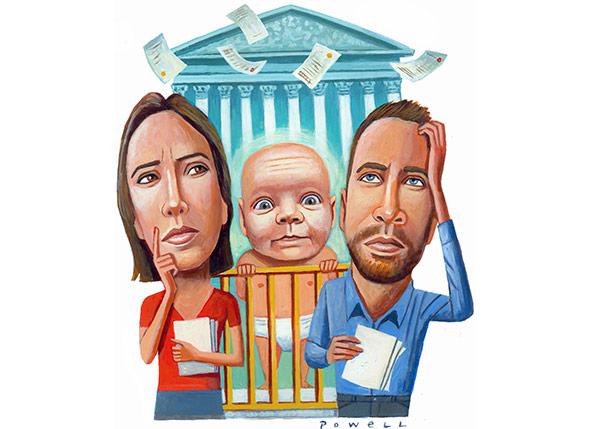

It turned out the true challenge was not retracting our baby-name-announcement email, but dealing with the court system in New York State, where the law isn’t set up to ease baby name regrets. To get the state Supreme Court judge to grant permission for us to change our son’s name, we needed things notarized and certified, and it took research and phone calls to figure it all out. As far as I can tell, we had to go through the same rigmarole for our newborn as we would have for our thirtysomething selves. I filled out an “Application for Index Number,” a “Request for Judicial Intervention,” a “Name Change Petition,” and a bunch of other forms, and then sought out the guidance of a kind lawyer friend who saved us a ton of money by helping with the lawyerly parts. He fixed the mistakes I’d made on the forms and made several trips to the Supreme Court to file the paperwork and hand in the $210 fee. Some weeks or months later (it’s a blur now), the judge sent a note granting us permission, but only if we first publicized his order in our local weekly newspaper. After that ran in infinitesimal type under the headline “LEGAL NOTICE” (“Notice is hereby given that an order entered by the Supreme Court, Westchester County … grants infant the right to assume the name of Lev …”) we had to obtain a notarized affidavit of publication and send that with the judge’s order to the state Department of Health to get the revised birth certificate. Meanwhile, at home, we’d long since started calling our son by his new name. In his baby book, filled out a few months after birth, he was both: “Liev (Lev).”

Friends ask why we changed our son’s name, and I’m aware as I’m telling it, that the story lacks a satisfying explanation. One name just seemed right until it seemed wrong, and the other felt wrong till it felt right. Feelings and seemings are perfectly appropriate reasons to give your kid a particular name in the first place, but if you’re changing his name, people naturally expect additional justification to explain going to such an unusual length. Gut sense doesn’t cut it.

I asked my daughter recently whether she remembered that her brother used to be Liev. She didn’t. She’s 5 now, with a 5-year-old’s quixotic memory, and a 5-year-old’s belief that what is now is what always will be and has been. He’s her brother. He steals her stuffed lion; he sits on her lap; he calls her “Ai-ee,” and we all relish the nickname. From her perspective, and ours, he’s who he’s supposed to be.