“Neil Armstrong’s widow finds artifacts from moonwalk in a closet” read the headline on CNN.com last week. Seeing the story brought me back to the day just over two years ago when a 26-foot moving truck pulled up in front of my house. My mom had called to warn me of the truck’s imminent arrival; nonetheless, I was dumbstruck when the guys opened the back gate and the sun poured in, revealing a cab tightly packed from floor to ceiling.

Inside was much of the contents of the house in Huntington Beach, California, that my mom shared with astronaut Charles “Pete” Conrad, commander of Apollo 12, the third man to walk on the moon. She was his second wife. They married in 1990, and he died in a motorcycle accident in July of 1999. She sold the house and put the bulk of the contents into storage—too grief-stricken to rummage through their memories, deciding what to keep and what to throw away. Now, almost 15 years after his death, what remained of the life he and my mom had shared had been shipped an hour north to me in Los Angeles.

Initially, I was excited by the prospect of opening this time capsule, but as the movers unloaded the truck and gradually covered every inch of my front lawn and most of my living room with boxes upon boxes, I became overwhelmed. I had just moved into this house that I had purchased and renovated with my wife, who, halfway through the renovation process, realized she wasn’t ready for marriage and split. My mom intended for these forgotten items, which for so long had remained locked in storage, to help me furnish my new house. But at that moment I lacked the space—both physical, and mental—for it all.

According to a blog post on the Smithsonian site, among the items Neil Armstrong’s widow discovered were the 16 mm camera that recorded Armstrong’s landing on the moon and a couple of waist tethers for securing the Apollo 11 astronauts. Unlike Mrs. Armstrong, I didn’t discover any Smithsonian-worthy artifacts. Those had already been donated, or given to Pete’s sons by his first marriage. Instead I found old clothing still in dry cleaning bags, yellowing files from the period when my mom and Pete were married, some worn leather briefcases, and a sizable collection of hats: a safari pith helmet, several Greek fishermen’s caps, and a beautiful gray stovepipe. There was also lots of furniture, the majority of which, unfortunately, didn’t really belong in my house. I was going for a mid-century modern sort of vibe. This furniture was best described as Southern California “eclectic.” For the most part, I discovered the same sorts of things you would find at any estate sale after someone passed away. Astronauts—they’re just like us.

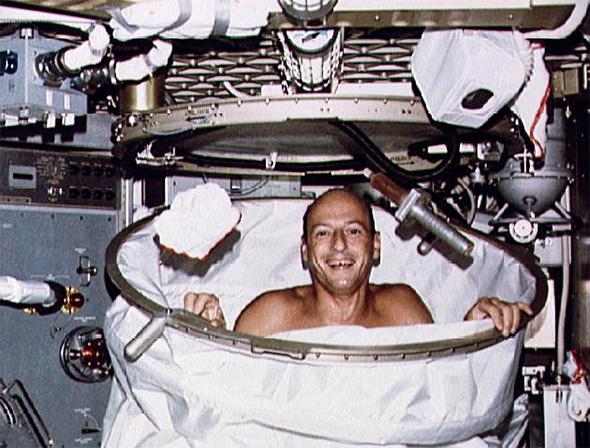

Photo by NASA via Wikimedia Commons

Pete—as everyone called him—was the love of my mother’s life. My mom and Pete had a great relationship, and she became the person she is today, in large part, thanks to him. He and I, on the other hand, had our differences. When they married, I was a characteristically dogmatic, liberal freshman at Wesleyan, and Pete was—well, he had a Navy anchor tattoo on his arm, and a photo of him shaking hands with Nixon on the wall of his office. Also, he had gone to the moon, whereas I had not.

He was a patriot—naturally—a stance my callow young self couldn’t stomach at the time, and a staunch Republican. Despite his diminutive stature (he was 5’6”), I saw him as an intimidating combination of Robert Duvall in Apocalypse Now and George C. Scott as Patton. One evening, just after George H.W. Bush launched Operation Desert Storm, I engaged in my own Operation Storming Out of a Restaurant—indignantly leaving the table after butting heads with Pete about the U.S. bombing of Iraq.

There, on my front lawn, amidst this sea of stuff that had just arrived, I found old feelings of juvenile resentment resurfacing. Why was all of this my responsibility?

Thankfully, my brother was in town and helped me sort through everything. I posted an ad on Craigslist for an estate sale, starting at 9 a.m. the following morning. At 7 a.m. the next day, the scavengers began arriving. By late afternoon, much of it was gone.

An old lamp. A painted wooden toucan on a brass perch. A table, the base of which was fashioned from an old pair of cowboy boots. As the objects from my mom and Pete’s marriage were gradually dispersed, I was reminded that although Pete and I didn’t share political views, I couldn’t help but appreciate his legendary sense of humor. When he stepped off the ladder of the Apollo 12 lunar module on to the lunar surface he said, “Whoopee! Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that’s a long one for me.” He was a raconteur of the highest order, and I recall nights when we ate sushi, drank sake, and my hostility was disarmed by his hilarious tales of travels both around, and out of this world. While visiting Japan once, a Buddhist monk in the town of Tenri asked Pete if, when he was in space, he saw God. “I didn’t,” Pete replied. “But if you wanna go look, I’ll drive.”

The next day, I gathered what remained (including the hats, which I saved) and returned it all, once again, to storage. As I was cleaning up the driveway, I stumbled upon Pete’s frequent-flyer ID card, from TWA. I stood there for a minute, looking at it, thinking: A guy walks on the moon, and then, the quotidian objects of his life randomly find their way into my yard in Los Angeles. How strange it was to hold this token of flight, albeit the type of flight we mere mortals take all the time rather than the otherworldly sort that Pete set records doing. I keep it in my desk drawer.