This is, for my firstborn, the sweet summer we all had once—or at least the summer we remember having, or the summer we should have had. It’s the summer before he and his friends leave for college. These are bright shining kids, whom I’ve no doubt embarrassed by quoting to them from Whitman’s “Song of the Open Road.” My son is already at least half-gone: sleeping at friends’ houses a few nights a week after band practice, until he returns the favor and I walk through our house at daybreak to find 18-year-olds asleep on every couch and in every spare bed.

By day—and some evenings—he seats customers or busses tables at a local restaurant. When he’s not working, he and his band are practicing, recording, or playing house-party gigs in sketchy neighborhoods. And then come the late nights, when a rotating crew of six or seven almost-adults gathers in our backyard to drink beer (if they can get it), smoke cigarettes (not always tobacco, I’m pretty sure), and—most crucially—talk. And talk, and talk, and talk, with Neil Young or Lou Reed or some group I’ve never heard of playing in the background, until the D.C. summer air finally cools, at least a bit, and the girls go home and the boys come in to sleep. Some nights, I smell bacon cooking downstairs at 3 a.m. Some nights, light streaks the sky before the salon finally breaks up.

Yes, salon, although they would certainly dismiss the word as the product of yet another pretentious adult. Despite the beer and the smoking, these are not raucous parties held for the sole purpose of obliteration by frat-boys-in-training. I can’t make out exactly what they’re saying (nor would I want to), but I’ve talked enough with these kids over the years to know that what goes on in our backyard is inane 18-year-old chatter intertwined with the urgent work of telling each other how very important everything in the world is, reassuring each other that adults are truly ignorant (and probably soulless), and wondering aloud where Whitman’s open road will indeed take them.

Even if my son somehow forgets this summer, I never will. I love bantering with his friends before they head out back and I head up to bed, their calls of “Goodnight, Mr. Ohanian” echoing in my head like a more sincere (I hope!) version of Eddie Haskell and his “Why, hello, Mrs. Cleaver!” I love the ritual of going downstairs at least twice in the first hour to remind them to keep the noise down so the neighbors—and his mother and I—can sleep. I love seeing the boys splayed throughout our house in the morning, dead to the world when I leave for the office at 8:15 and, if they don’t have to work that day, still down for the count until 11 or so. I love falling asleep to the sounds of their voices, as animated as they are unintelligible, floating up through my bedroom window screen. I cherish the noise because soon there will be silence, although our second-born will do her best to fill it up.

And I love that it’s the summer of another birth for them, more monumental than they can possibly imagine. It’s the summer before they’re pushed, ready or not, into a world big and loud and confusing and full of promise (and, perhaps, peril). I wouldn’t trade places with them; I’ve had my time, years ago on the other coast, where at night we skinny-dipped in the Pacific or poured beer over our heads in the dry bed of the San Gabriel River and then drove home to sit on the patio and look up at the palm fronds outlined dark against the stars. But I’d love another summer like theirs, talking with friends all night about everything and nothing in the same sentence, the only light flickering when someone strikes a match.

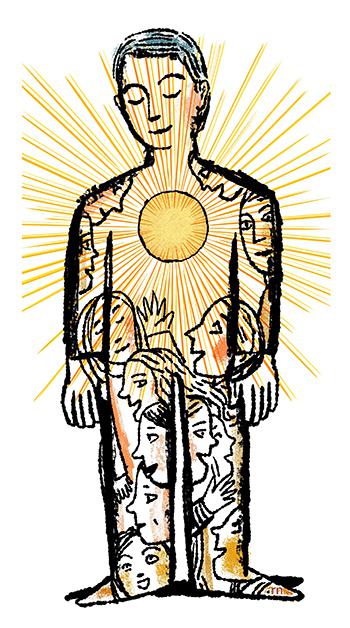

In the meantime, I’ll have to settle for my own monumental summer. My impending birth is the birth of a different father, whose work is most certainly not done but just as certainly will change more this year than it has in 18 years. From now on, I’ll need to pick my spots more carefully and bite my tongue more often. While my son’s life is still more mine than it’ll be five years from now, it’s also about to become much more his than it’s ever been.

This is how it should be, of course. I can’t begrudge him his growing up. All I can do, if the nights get too quiet after he’s gone, is go downstairs in the darkness to fry up some bacon and put on some Neil Young, and remember the best summer—so far—of my son’s unfolding life.