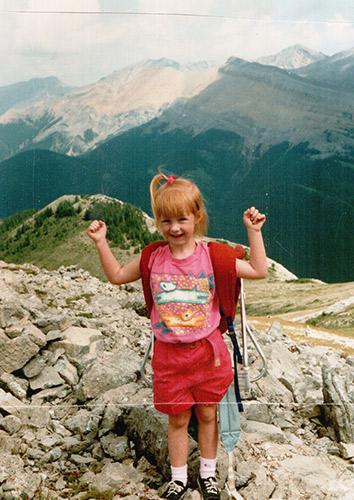

In a stack of old papers in my parents’ house is a photograph of 5-year-old Amanda standing at the edge of Sulphur Ridge in Canada’s Jasper National Park. I’m on a pile of rocks 6,000 feet in the air with a red Pebbles ponytail springing out of the top of my head and my scrawny arms raised in the international symbol of triumph. I look like I climbed there, but really my mom hauled me up in a big red hiker’s backpack fitted with two little holes for a child’s legs. My brother, old enough to be freed from the confines of a kiddy backpack, had arranged an every-other-switchback piggyback system with my father to get them both to the summit. Right before they snapped the photo, my parents slipped the backpack onto my shoulders to make it look as if I had been the one carrying the weight.

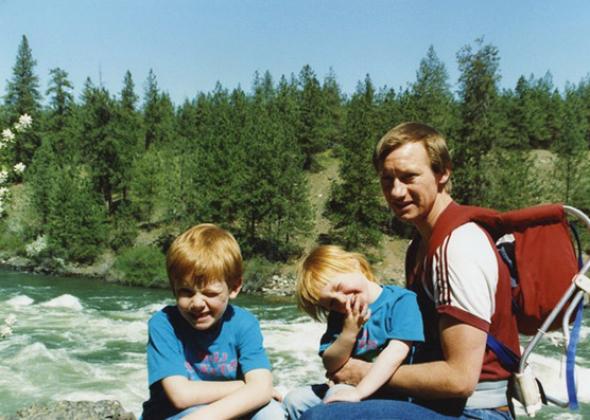

Courtesy of Amanda Hess

This is how it was for as long as I can remember: always a few steps behind, impatient to catch up. Mike was born two and a half years before me, and as soon as I was capable of rudimentary declarations of free will, I demanded to go wherever he went. Our sibling rivalries were typically sparked by Mike ambushing me in the yard, holding my arms to the ground, and threatening to drool on my face; they were ultimately resolved when he climbed to the highest tree branch while I clawed ineffectually at the trunk.

When I was 3, my parents tried to plop me into a ski resort day care so the three of them could explore the mountain, but apparently I refused to sit around rearranging blocks with those other babies. My mom tried unsuccessfully to position me between her legs and launch me onto my own skis, pulling me up again and again as I plunked my butt onto the snow instead of attempting a turn. After an exhausting hour, she escaped with my brother while my dad and I languished on the bunny hill, trying to advance me past the snowplow. Dad would ski backwards in front of me, holding my tiny skis into a V-shape, until, finally, I managed to put my skis side by side and pivot on the snow. When my dad tells this story, he throws his arms in the air and launches into my tiny kid voice: “Daddy! I can ski!”

A few years later, I was accompanying him on black diamond runs with moguls as tall as me. When goggled adults riding high above us on the chairlift pointed at me in awe (or else at my father in disgust), I got a rush that sustained me until the bottom of the hill, where my dad would remove my mittens and breathe warmth into them before fitting them back on my pink hands. I didn’t know to feel lucky to be a little girl with a father who took her along on all of his adventures. I just liked that I could keep up with my dad.

I couldn’t, always. At a Canadian campground, my parents instructed 8-year-old me to follow my brother down the 500-yard path to the lake, but I lost sight of him and ended up tracing the campground’s circular tracts for what seemed like hours, the lone kayak paddle I’d been tasked with carrying slowly turning my arms to jelly. Midway down the slope on a frigid day at Mission Ridge, I biffed into the snow. Instead of getting back up, I threw off my gloves and unlatched my skis, chucked them all down the hill, planted on my stomach, and pounded the snow to execute my full-blown temper tantrum. (“I could have had a dog,” my dad reminded me as I set to work on my boot buckles.) Once, after a few hours exploring the trails of Mount Spokane on cross-country skis, my dad left me to defrost in a woodfire-heated lodge while he went back to the snow. I sat alone eating a packed peanut butter sandwich when an older man spied me from across the room, angrily approached, and asked: “Where is your father?” These incidents stand out in my memory like a spike on a heart monitor. One minute I’m sailing over a blanket of white snow, and the next I’m a red-faced little kid who’s in way over her head.

My dad listened more than he talked, but I absorbed every throwaway detail I picked up about his childhood in small-town Wisconsin. He had a friend named Gunner who blew up a shed with dynamite. He took a semester off from college to do … something in Jamaica. It wasn’t until later that my mom began sketching in the more complicated details. My father’s father had died of his fourth heart attack when my dad was 9 and my grandmother was one-month pregnant with their fifth child. She became everything to those kids—breadwinner, caretaker, Catholic school gym teacher. One Christmas, when I was 1½, my mother was holding me in her lap at my dad’s childhood kitchen table when my grandmother emerged with a shoebox full of obituary clippings, all for men in the family whose hearts had failed at 40.

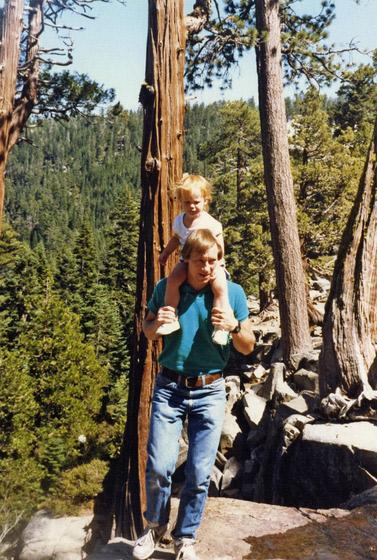

Courtesy of Amanda Hess

Back at home, my mom pushed my 35-year-old father to head to the doctor and undergo a battery of tests. His cholesterol was through the roof. Mom left town to attend her grandfather’s funeral, and returned five days later to find Mike and me tearing through the house as my dad lay flat on his back, 10 pounds lighter than when she’d left him, his new drug regimen pummeling his liver. By the time I was 5, mom was gone for long summer stretches, studying at a Cleveland graduate program she hoped would stabilize her career in case our other source of income suddenly disappeared. But to me, my father was invincible. Once, he lost control of his skis, crashed into a tree trunk, and flopped backwards under a pile of snow. My brother and I stood around bored, waiting for him to pop back up and race us down the hill.

By the time I finished elementary school, I had reached my terminal height of 5’4”, and in that brief period where girls transform before boys do, I was as tall as my brother. I didn’t like it. The clarity I used to find while hiking got clouded with embarrassment at the folds of my arms over a tank top strap and the feel of my thighs rubbing together. I started hauling a giant sparkling blue makeup box with me on family camping trips, where I’d disappear into a tent and unfold its vanity mirror to check my clumsy makeup job. My dad stared at the box like it was a ticking time bomb.

* * *

Down was supposed to be the easy part. This was eighth grade, Arizona, where my mom had moved for a better job, and my brother and I had followed a year later. (My parents stayed together, but, now both college professors, they never managed to find work in the same place.) I hated everything here. Trees didn’t grow and it never snowed. All the girls had platinum highlights. I was hard on my mom, who was tasked with rousing me out of bed every morning and reasoning with me through slammed doors. My dad visited on weekends and school breaks, and I’d sulkingly agree to accompany him on the excursions that I’d once demanded to be included on. He’d drive me out past the empty strip malls to some desert trail where we squeezed through 30-foot boulders as lizards scattered around our feet. But today, we were descending into the Grand Canyon, where he’d planned out a 23-mile march down to the Colorado River and back up to the opposite rim. Signposts warned hikers not to try to reach the river and return in one day, but signs were written for other people.

Just a few miles in, my dad and brother were gliding easily down switchback after switchback, and my short legs were struggling to keep pace. By the time we hit the valley, it was 90 degrees and we had 10 miles more to go before we reached the opposite canyon wall and started climbing the seven miles back up. We called my mom from the payphone at Phantom Ranch and ate ice cream sandwiches. As soon as we started the ascent, the hard rock gave way to a long stretch of pliant sand, and I fell further and further behind as my legs struggled to dig out of it. My dad found me huddled in a shaded alcove in the cliff face, looking like some wounded animal that had crawled into a hole to die. I cried because I couldn’t do it, and then because I was being a baby, and because crying made walking even more impossible, and because my dad was watching. Dealing with a weeping 13-year-old girl was generally my mother’s responsibility, but my dad had led me to a desert one mile into the ground and now he had to get me out of it. He walked me down to a beach by the river and took off our shoes, and we sat for a while with our feet in the water. My dad pointed up to tiny specks at the top of the rim and convinced me that we would soon be joining them.

Courtesy of Amanda Hess

When we finally stood up, afternoon shadows were beginning to cool the canyon, and I discovered that my stocky legs could be an asset on the ascent. Halfway up, Mike took a photo of me and Dad, him grinning and me affecting my usual dead-eyed stare. But privately, I was thrilled to be reminded that my body could be useful for something other than reflecting my insecurities, and I led my dad and brother to the rim. At the top we found a billboard with a taped photograph of a man zipped into a body bag, a warning not to attempt what we’d just done, and we all laughed uncomfortably.

By high school, I was outpacing my dad on our 5-mile runs, and when I went off to college, I ran as far away as I could, to a city on the East Coast I could barely even picture in my head. The next summer, I was back in Phoenix, working, when my dad set off on a weeklong rafting trip without me. It was the first one I’d ever missed. I spent that summer driving between pockets of air-conditioning—the library, the Checkers drive-in, the mall, the other mall—and was wandering the aisles of the hardware store when my mom called me on my cell. For a second it sounded like the connection was off. Then she said, “Dad’s fine.”

The night before they were set to launch the boats, he had woken up in the dark in middle-of-nowhere Oregon struggling to breathe. Thinking it was a heart attack, he took a bunch of ibuprofen, mistaking it for aspirin. My uncle drove him to the nearest hospital—I don’t want to think about what they would have done had they been halfway down the river—and doctors told him that one of his lungs had detached from its tube and collapsed in his chest. When I finally saw him, he had a drainage bag that exited into, for some reason, a plastic glove. My dad smiled, took the glove in his hand, and waved it at me.

When I was little, always relegated to the kiddy backpack or the backseat, I tried to take control of my situation by whining: Where are we going? How do we get there? How long is it? Mike won’t stop touching me! I got annoyed when my dad veered us off the trail to cut through the forest, always concerned that I wouldn’t be able to find my way back on my own. Suddenly, I was worried about someone other than myself. In my eagerness to get older, I hadn’t considered that my parents would age with me.

On a trip back to Phoenix a few years ago, my dad and I drove to one of his favorite preserves and we hiked off trail up a rocky hill lined with the shells of saguaros. When we turned back, my dad—always faster on the downhill—headed out in front of me, and after a while, I found myself alone in the middle of the scratchy brush, having accidentally veered off course while lost in my own thoughts. But I spied the foot trail we had planned to hit on the way back to the car and started jogging to catch up. Minutes passed without any sign of his tan, floppy hat bobbing in the distance. He had our backpack with both of our cellphones and all of the water. Had he fallen somewhere? Are there snakes? Hikers buzzed past me. “I lost my dad,” I thought to myself but didn’t say. Instead, I picked up the pace and ran to the trail’s end, where the dirt pooled out into the asphalt parking lot. No Dad. I finally flagged down a woman outside the bathroom, breathlessly borrowed her cellphone, and called my own number. I heard rings, a fumbling noise, and his voice. He had waited for me right at the top of the trail, and, when I failed to appear, pounded back and forth terrified, stopping hikers to ask if they’d sighted me.

Last month, I flew into Phoenix and drove the four hours north back to the Grand Canyon with my dad. This time, we would head down and up the same rim, a comparatively easy 14-mile route, and it would be just the two of us. About a mile in, most of the hikers who had started in with us fell far behind, or else turned back. As we wound further down, only one group kept up with us—a pack of three lithe, bronzed hikers swathed in neon tank tops who didn’t look a day over 19. The five of us passed back and forth, back and forth, until we reached the river, where they promptly removed their shirts, exposing their taut abdominals to the blazing sun while my dad and I rested under matching sweat-logged long-underwear tops and floppy-brimmed hats. As we headed into that sandy stretch of trail, they passed us one last time, and we never saw them again.

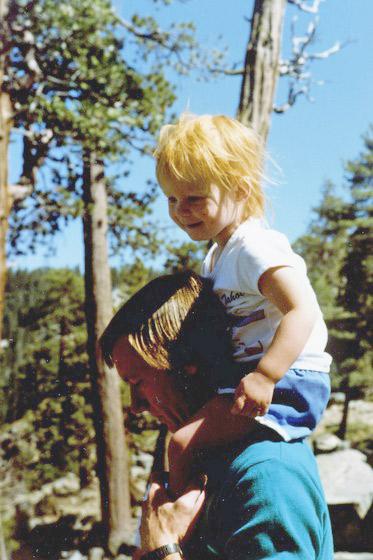

Courtesy of Amanda Hess

I kept it together until we reached the Indian Garden Campground, a shady rest area about 5 miles down from the South Rim. My dad grabbed a handful of trail mix, ate the peanuts and almonds that I had been picking around all day, and deposited a pure cache of sunflower seeds into my palm. We poked our hiking poles at the squirrels that swarmed around our snacks, which signs warned us carried fleas, which carried the plague. But as soon as we headed back up the trail and into the sun, my breath drew loud and thin in my chest. We were losing oxygen with every foot we marched into the sky, but my face was still red with heat, and my leg muscles were seizing from the strain. As my dad marched on, I could manage about 10 feet at a time until I had to stop and hunch over my poles. My 62-year-old father was totally destroying me.

As I languished under the final set of switchbacks, my dad turned back, clapped me on my shoulder, and pointed up. “Do you see those people? They’re at the top,” he said. “How nice for them,” I replied, slipping back into tortured adolescent mode. But this time, when I felt the panic rise into my chest, I breathed deeper and focused on timing my steps right behind his. In the final stretch, the trail became congested with flip-flopped tourists who had dipped into the canyon for an easy jaunt, as if to taunt us with their unused stores of energy. As we panted toward the finish, they posed and grinned for their cellphone cameras, converting the trail we’d just conquered into their scenic backdrop. We lurched almost motionlessly to the rim, where I tried to raise my poles into the air and collapsed into my dad’s arms. “Those fuckers,” I said to my dad when we got into the car. “They have no idea where we’ve been.” He nodded in agreement and drove me home.