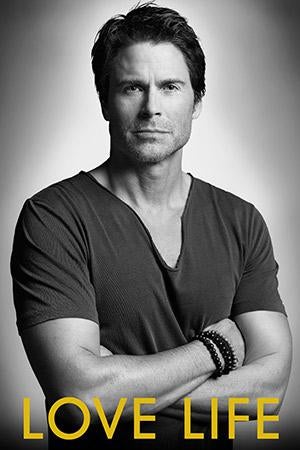

With many parents of high school seniors prepare to send their kids off to college in the fall, Slate wanted to share one father’s experience of coming to terms with this next chapter in parenthood. That father just happens to be Rob Lowe. The following is adapted from Lowe’s memoir, Love Life, published by Simon & Schuster in April.

I’m trying to remember when I felt like this before. Like an elephant is sitting on my chest, like my throat is so tight and constricted that I can feel its tendons, like my eyes are 100 percent water, spilling out at will, down pathways on my face that have been dry for as long as I can think of. I’m trying to remember: When was the last time my heart was breaking?

The death of my mother was one time, but her passing was prolonged enough to let me prepare for it, to the extent anyone can. At the most intense moment, sitting at her gravesite, I felt like I could hear every leaf blower in a 50-mile radius, felt as if I could feel the sun’s rays turning my skin darker shades with each second, my skin irritated and jumpy, making me want to crawl out of it. I’m feeling it all now again, but no one has died.

When I was a boy, I had to leave my friends in the summer, just as Malibu was becoming Malibu, say goodbye to my first girlfriend and go to Ohio to stay with my dad. There is a little of that sense memory at play too, a feeling that I’m about to be left out of important events, separated from life as I know it, the world as I love it.

I am remembering and feeling the details of my parents’ divorce and our family’s forced march out of my home to an alien world across the country. The goodbyes to my father and my beloved grandparents; rationally I knew I would see them all again, but now I have the same body-deadening weight of the condemned, counting the minutes until the final moments of a life that’s all I’ve ever known. This encompassing, exhausting sadness I had mostly forgotten, or buried, until now.

Today is my son Matthew’s last night home before college.

I have been emotionally blindsided. I know that this is a rite many have been through, that this is nothing unique. I know that this is all good news; my son will go to a great school, something we as a family have worked hard at for many years. I know that this is his finest hour. But looking at his suitcases on his bed, his New England Patriots posters on the wall, and his dog watching him pack, sends me out of the room to a hidden corner where I can’t stop crying.

Through the grief I feel a rising embarrassment. “Jesus Christ, pull yourself together, man!” I tell myself. There are parents sending their kids off to battle zones, or putting them into rehabs and many other more legitimately emotional situations, all over our country. How dare I feel so shattered? What the hell is going on?

One of the great gifts of my life has been having my two boys and, through them, exploring the mysterious, complicated and charged relationship between fathers and sons. As I try to raise them, I discover the depth and currents of not only our relationship but ones already downstream, the love and loss that flowed between my father and me and how that bond is so powerful.

After my parents’ divorce, when I was 4, I spent weekends with my dad, before we finally moved to California. By the time Sunday rolled around, I was incapable of enjoying the day’s activities, of being in the moment, because I was already dreading the inevitable goodbye of Sunday evening. Trips to the mall, miniature golf, or movies had me in a foggy, lump-throated daze long before my dad would drop me home and drive away.

Now, standing among the accumulation of the life of a little boy he no longer is, I look at my own young doppelgänger and realize: it’s me who has become a boy again. All my heavy-chested sadness, loss and longing to hold on to things as they used to be are back, sweeping over me as they did when I was a child.

In front of Matthew I’m doing some of the best acting of my career. I’ve said before that the common perception that all good actors should be good liars is exactly the opposite; only bad actors lie when they act. But now I’m using the tricks of every hack and presenting a dishonest front to my son and wife. To my surprise, it appears to be working. I smile like a jack-o’-lantern and affect a breezy, casual manner. Positive sentences only and nothing but enthusiasm framing my answers to Matthew’s questions.

“Do you think it’s cold in the dorms in the winter?” he asks in a voice that seems smaller than it was just days ago.

“Naah!” I lie, having no idea what his new room for the next four years will be like.

This line of questioning is irrelevant anyway, as my wife Sheryl is preparing for any possible scenario, as is her genius. We all have our strengths; among hers is the ability to put anything a human being could possibly need in a suitcase. Or box. Or FedEx container. She is channeling her extraordinary love and loss into a beautiful display of preparing her son for his travels. And in the end, Arctic explorers will travel lighter.

Matthew’s dog, Buster, watches me watching Matthew as he sorts through his winter jackets. I am one of those people who believe dogs can actually smile, and now I can expand that belief to include an ability to look incredulous as well. Buster seems to be the only member of our family to see what a wreck I am, and he is having none of it.

“You disgust me,” he seems to say, looking at me with his chocolate eyes. “Get a backbone, man!”

The clothes are off the bed and zipped into the bags. The bed is tidy and spare; it already has the feel of a guest bed, which, I realize to my horror, it will become. I replay wrapping him in his favorite blanket like a burrito. This was our nightly ritual until the night he said in an offhanded way, “Daddy, I don’t think I need blanky tonight.” (And I thought that was a tough evening!)

I think of all the times we lay among the covers reading, first me to him, Goodnight Moon and The Giving Tree, and later him to me: my lines from The West Wing or a movie I was shooting. The countless hours of the History Channel and Deadliest Catch; the quiet sanctuary where I could sneak in and grab some shut-eye with him when I had an early call time on set, while the rest of the house was still bustling. I look at the bed and think of all the recent times when I was annoyed at how late he was sleeping. I’ll never have to worry about that again, I realize. I make up an excuse to leave the room and head to my secret corner.

For his part, Matthew has been a rock. He is naturally very even-keeled, rarely emotional; he is a logical, tough pragmatist. He would have made a great Spartan. True to form, he is treating his impending departure as just another day at the office. And I’m glad. After all, someone’s gotta be strong about this.

Our youngest, Johnowen, will be staying behind and returning to high school, and now it’s time for them to say goodbye. I’ve been worried about how Johnowen will handle the departure of his big brother. Only two years apart, they share most of the same friends, which is to say that Johnny hangs with all the older boys who are also leaving home. My sons are very close in that vaguely annoyed constant companionship that brothers can share (if they are lucky).

Now what will happen to their NFL rivalry and smack talk? The nightly ear-splitting deconstructing of Scandinavian dubstep EDM? The incessant wrangling about what guys and what girls are coming by and when? Life is breaking up the team that kept me in loving consternation until all hours of the morning and throughout those never-ending summer nights.

I am a boy again as I wonder: What will become of my two closest friends?

In the driveway Matthew gives Johnowen a laconic high-five. “Peace,” he says, clearly going out of his way to avoid any emotion or drama. Johnowen, whose passion runs just barely under the surface, is a little taken aback. He looks at me, sad and bemused, and I know what he is thinking: “That’s my brother! A cool cucumber till the end.” He watches Matthew hop into the car for the ride to the airport.

Of the many horrors of divorce, the most egregious is that it robs a kid of the best of both worlds. Dads can do many things that even the best moms can’t, and vice versa. I’ve always been fascinated by whom my kids come to and for what purpose, whether they are drawn to Sheryl or to me, and I’ve noted that it always surprises me which one of us they need for comfort or advice and when.

On the plane, we have two seats together and one apart. Matthew chooses to sit with Sheryl and I see how happy it makes her. Then on go the headphones and not a word is shared for most of the flight. Sheryl and I look at each other and smile. “Teenagers.”

An amber, evening light fills the cabin as we flee the setting sun, heading east. I’ve taken a break from reading and am staring at my boy. The light from his window is cutting across his face, accentuating his cheekbones and strong jawline, making him look unbearably handsome and grown-up. He might as well be a young businessman headed to a meeting.

His favorite headphones are on and he is reading, so I can consider him in freedom, without his awareness. I remember the first time I laid eyes on him in the delivery room. “He’s blond!” was my first thought. And I remember what I whispered to him when his eyes opened for the first time in his life as he peered in my face, and (I am convinced) into my soul. “Hello, I’m your daddy. And I will always be there for you.”

Sheryl has looked up from her iPad and mouths to me, “Are you okay?” I want to be, for her; I don’t need her worrying about anything other than the logistics ahead, and I certainly don’t want to draw any attention on the plane. But something about her face and the way she is looking at me, while I am looking at him, pulls the rug out again and I avert my eyes from her, from him; my sunglasses go on and I open up a newspaper, covering my entire face and anything that anyone might see, like a bad version of Maxwell Smart hiding from a KAOS agent. I am amazed that so much water can come out of the eyes of someone who dehydrates himself with so much caffeine.

Just as we land, I take one more peek at Matthew. If he has any emotion about any of this, he is not showing it. I’m proud that he is charging into this chapter that opens the narrative of his adult life with such confidence. And I sneak another peek at Sheryl and allow myself to think, “All of this is exactly as it needs to be.”

* * *

It’s move-in day. We drive onto the historic, grand, and beautifully intimidating campus with our rental car packed with Matthew’s belongings. Stuck in a nonmoving lineup of cars filled with other parents in the same emotional boat, I am cursed again with idle time to contemplate the day ahead of me. But today, for the first time, the overpowering melancholy is gone, the bittersweet nostalgia too, replaced by an envious, excited adrenaline. To be at the true beginning! To be moments away from meeting strangers, some of whom will be in, and change, the course of your life forever! To have the opportunity an elite university provides to be able to discover yourself, your true adult self, away from any of the tentacles of childhood! I feel the gooseflesh rising from my arms.

I didn’t go to college. At 17, I left home to go on location for my first movie. The first private space of my own wasn’t a dorm room; it was a hotel room in Tulsa, Oklahoma. I didn’t have to navigate a brand-new, totally foreign ecosystem of fellow students and faculty; I was thrown unceremoniously into a strange group of actors and crewmembers. And I had the knowledge that for good or bad, it would all be over in three months, not four years. Now, for the first time that I can think of, I have no personal life experience to draw from to guide my son. My first and only college experience will be through him.

Unloading in front of the Gothic-style dorm, the welcoming upperclassmen do crazy, exuberant dances and grab boxes to help. These are the RAs of the dorm, the first bit of much new collegiate vocabulary I will learn along with my son.

He and I leave Sheryl to do her masterwork in his corner, hardwood-floored room. She will handle the important groundwork of his comfort for the next year. I will handle other issues: finding the best pizza, finding a gym where he can continue jujitsu, the purchase of a bicycle and where to stash it. Sheryl’s immaculate and detailed renovation is an OCD and maternal-love-fueled epic poem of logistics and labor, so Matthew and I have plenty of time to explore and just spend time together.

I’m surprised at how little we say to each other, and how good that feels. There is nothing we are withholding and I know that our “being current” with each other, as the shrinks would say, is a result of years spent in each other’s company. Not just dinner or good-nights or drop-offs; it’s time coaching his teams, being in the stands, on fishing boats, in the water surfing or diving, watching stupid television, being home on nights when he is with his friends and talking smack with them, standing up to and getting in the face of teachers, parents, other kids or anyone who so much as thought about treating him badly.

We put in the time together; we built this thing we have of comfort and love. And now, as we both prepare to let go of each other, it is paying off. That evening, even though his dorm room is ready he says, “Dad, I think I’ll just stay with you and Mom tonight.” I catch Sheryl’s eye; this time, it’s hers that are moist.

The next morning, after all of the freshmen file out of the massive and imposing chapel after convocation, Matthew shows his first signs of uncertainty. The president’s speech was an ode to the incoming achievers, “the most highly accomplished” class ever accepted in “the most competitive year” in the school’s history. It took this elegant ceremony, in a setting both beautiful and intimidating, among a sea of strangers, some of the best kids our country has to offer, for Matthew to realize the stakes. He did it. This is real. He is here. This is happening.

“Dad, what if it’s too hard for me here?” he asks me later, sitting on his fold-out bed back at the hotel, looking more “fresh” than “man.”

“You came from a very tough academic school with great grades. You took the tests, you got the scores, you did the hours and you did the travel and extracurriculars. You made it happen. No one else. This won’t be any different. This school chose you because they know you can succeed here.”

“None of the other kids look scared at all,” he says, and for the first time I can remember since he was a baby, I can see his eyes welling up. I want to reach out and hug him, but I don’t. Instead I look him in the eye.

“Never compare your insides to someone else’s outsides.”

He nods and turns away.

“I think I might take a nap.”

“Sure, I’ll wake you in a while,” I say.

He curls up in a ball, like he used to. I unfold a blanket and cover him, tucking it underneath, rolling him in it, like a burrito.

* * *

The students who populate the university are impressive. These are the ones who didn’t dumb it down to be cool, the ones who were unabashed about learning and loved doing it. Anyone feeling anxious about the future of our country should spend a couple of days on our college campuses. These kids are studs.

Matthew meets friends quickly, a great group of freshmen from all over the country.

“Dad, they all can’t believe I left Southern California. They all want to go there.”

“This is exactly how you will get to live in Southern California if you want to. You will earn it here,” I tell him at a good-bye dinner Sheryl and I have put together for him and his new pals. He nods in his solemn way.

After dinner the gang plans on going to one of the local nightspots. “Dad, you gotta come!” He insists, and I know, like me, he is playing to delay the end of the evening. I leave before sunrise in the morning. Sheryl will stay later (I have to be back at Parks and Recreation by noon to shoot a full day) and she urges me to go. “Do it. He wants to be with you. I’ll drop you off.”

But at the hot spot it is wall-to-wall kids, easily a couple hundred of them, raucous and spilling out into the street. I know I can’t wade into a group like that unnoticed. Matthew knows it too.

“Honey, I can’t go in there,” I say as everyone piles out of our rental car.

“I know, Dad.”

We lock eyes for the tiniest beat. I want to see what, if anything, he will say. His new “bros” are already striding to the club and he doesn’t want to be left behind. This is the college good-bye I’ve heard so much about and dreaded so deeply.

I close in to hug him, but he puts just one arm around me, a half hug. “Peace,” he says, a phrase I’d never heard him use until he said the same thing to his little brother in the driveway. Then he turns on his heel and strides away. From his body language I know he won’t turn to look back; I know why and I’m glad. I watch him until I can’t see him anymore, until he’s swallowed up by his new friends and his new life.

Adapted from Love Life by Rob Lowe. Copyright © 2014 by Rob Lowe. Printed by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.