On a Saturday afternoon in April 1992, when I was 13, my father told me we needed to talk. We sat on the itchy baby-blue blanket on my bed in the room I shared with my 8-year-old brother. I didn’t know what he was going to tell me. I already knew. I didn’t want to know.

For the previous four months, my father had been in and out of the hospital in Lexington, Ky., half an hour from this rented duplex in Richmond, where he’d lived since he and my mother divorced three years earlier. Dad taught business law at Eastern Kentucky University and served as a deacon at our church. Since my brother and I spent most of our time with my mother and stepfather, two hours from Dad in a small town south of Louisville, his life seemed far away when we weren’t with him. I knew he’d had some kind of “blood problem” for a while; he’d explained that much when we accompanied him to get his blood drawn during our summers together. “Like leukemia?” I once asked, as we drove away from the doctor’s office, thinking of the hokey Lurlene McDaniels books scattered around my middle school classrooms, in which innocent cheerleaders bravely fought some sort of cancer or another, hoping to get one kiss before they died. “Something like that,” he answered.

My father seemed healthy. He ate lots of fresh salads, played racquetball in the mornings, headed off to the gym in the afternoons, duffel bag slung over his shoulder. On summer evenings after dinner, we’d take long walks, bringing stale bread to a flock of ducks at a nearby pond, or circling the track at the university, chatting about whatever Peter Jennings had mentioned that night on the news, my brother running in front of us. Sometimes we held hands as we walked.

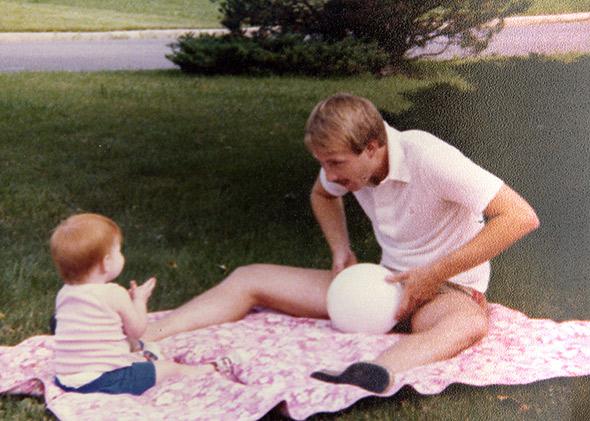

The author and her father, playing ball in the yard.

Photo courtesy Whitney Joiner

There were signs that everything wasn’t OK. In December 1991 Dad called to tell me he needed some kind of anal surgery. It was so bizarre and removed from my day-to-day—the basketball games, the first boyfriend—that I didn’t ask too many questions. I was an insatiably curious straight-A student, and yet, I never once said to my father or mother, “So, is this related to the blood thing?” Thinking back on it now, it must have been purposeful obliviousness: Let’s keep this going—life as it is now—as long as we can.

A few weeks after the surgery, Dad was back in the hospital. The doctors had found a brain lesion. Dementia. I tried to ignore the wacky things he said during visiting hours. It was when he was finally released, home again, and OK enough to care for us over a weekend, that he told me we should talk.

“I’m HIV-positive,” he said, his voice breaking, as we sat facing each other on the bed.

I knew what this meant. I had a subscription to Time. I’d read about AIDS, the lack of a cure, Ronald Reagan, Ryan White, the firebombed houses of victims. I knew that he was definitely going to die, in the next few years, if not sooner, and in the most unacceptable way possible, of a disease I’d seen mostly accompanied by picketers and slogans on the news. My classmates casually tossed off their opinions about AIDS on a regular basis: that everyone with HIV should be shipped off to an island, that it was a cure for fags, that they deserved it.

I also knew that my dad must be gay—because, well, of course. While I’d never met an out gay man, I kind of knew what they were supposed to be like from movies and TV, and Dad fit the mold: He loved to cook; he cleaned obsessively; he kept the International Male catalog around, because, he said, “I like the clothes.” Dad never dated after the divorce—he didn’t even notice women when they walked by. The idea of my father paired up with another woman seemed totally unnatural and absurd to me, and selfishly, I didn’t mind. I loved being the only girl in his life.

“You know,” I said to Dad, “I asked Mom once if you were gay.” Asking, but not asking.

“Gay?” he scoffed, taken aback, disgusted. “I’m not gay.” You can get it from women too, you know. He’d cheated on Mom, just once, during a conference in Nashville, years ago. A flight attendant. One mistake.

* * *

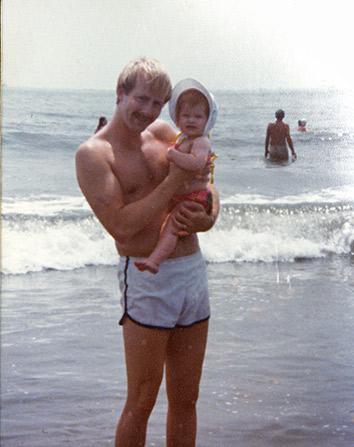

Photo courtesy Whitney Joiner

Five months later, a few weeks into my freshman year of high school, my father died. Mom confirmed what I’d already guessed—“Is there anything you want to ask about your father?” she’d said in our kitchen—after a long conversation she’d had with an openly gay friend from college, Pat, who had, apparently, been a confidant of Dad’s. I know it sounds strange, but I don’t remember anything else from that conversation—how I felt, what I said. Years later Mom told me that, according to Pat, Dad had been active in Lexington and Louisville’s gay club scene. “You don’t know how hard it is,” Pat had tried to explain.

There were no AIDS activist organizations, no ACT UP, no PFLAG in Bullitt County, Ky. And even if there had been, I’m not sure I would have joined. I barely knew anyone who’d lost a parent, much less one to AIDS, and my remaining relatives were furious at my father. To make that leap, to seek out other people who were going through similar experiences, I first would have had to stand up and say: This happened. My family wasn’t yet ready for that, and wouldn’t be for many years.

Other than a couple of lies I told in high school right after my Dad died (“of cancer”), I never actively hid my father’s identity. But I’ve never been open about it either. Despite being an editor and journalist for my entire career, I’ve never written about him, until now. I connected with my dad in smaller ways over the years instead: studying sexual politics and queer theory in college; watching Longtime Companion; standing with my brother and a throbbing crowd at Irving Plaza, 13 years after Dad’s death, as Erasure’s HIV-positive Andy Bell sang “Drama!” in massive sparkly angel wings. I danced that night for my father, who never got to see Bell sing, and left the show sweaty, wrung-out—and thrilled to feel connected to what I can only assume was a joyful part of my dad’s identity.

Every once in a while, my brother and I talk about the what-ifs: What if Dad had held out a little longer, if the drugs had been approved a little earlier, if time and the eventual softening of our culture would have softened him? Would he be meeting me for dinner in New York? Would I be flying to visit him in Louisville or Lexington with his middle-aged partner?

In some ways I think Dad was on the verge of coming out to me back then. When he went to see Truth or Dare with his hairdresser, Mickey, he told me about it. He sent me a starstruck postcard from London exclaiming, “Guess what? You know Jimmy Somerville from Erasure? I met him at a club here!!” (Never mind that Somerville was actually in Bronski Beat, another of Dad’s favorites.) But to actually let me in—to sit on that blue blanket, look me in the eye and tell me he was gay—was something he couldn’t do. It was probably one of the hardest conversations he’d had in his 38 years. I’m not angry about it; I just wish it had gone differently. I wish I could have known that some part of him accepted—and was proud of—who he was. “I asked Mom once if you were gay,” I would have said. And all he would’ve had to say in return was: I am.

Whitney Joiner is a senior editor at Marie Claire magazine. Along with Alysia Abbott, author of Fairyland: A Memoir of My Father, she is launching The Recollectors, a storytelling forum and digital community for people who have lost parents to AIDS. Their Kickstarter campaign to build TheRecollectors.com will remain live until Wednesday, April 16.