Many children on the autism spectrum develop affinities, or what we might call obsessions. They focus on things like train schedules, maps, baseball scores, video games, or, in the case of Owen Suskind, the subject of his father, Ron Suskind’s, new book, Life, Animated, classic Disney movies. We could also call these “affinities” passions, but the psychiatric establishment might object to that positive spin, because “affinities” are generally thought of as symptoms, signs of the child getting tangled up in his or her own repetitive thoughts. They are considered the autistic child’s way of warding off the world because it’s too scary or confusing to engage. If therapists indulge affinities, it’s generally as a reward for the child attempting appropriate social behavior. (Make eye contact and I’ll let you watch Aladdin).

But in Owen’s case, the opposite happened. Just shy of his third birthday, Owen developed regressive autism, meaning he essentially stopped communicating. One thing he still loved to do was watch Disney movies with his brother, and he’d watch the same scenes over and over, as his father recounts in this New York Times Magazine excerpt. Then one day, while watching The Little Mermaid, Owen said the first word he’d said in a while: “juicervose.” His mother Cornelia figured out that he was saying “just your voice,” from a song Ursula the sea witch sings to the mermaid Ariel. The family took that as a sign that Owen was looking for a way to get his voice back. From then on, Disney scripts became the language the Suskind family used to communicate with Owen, literally, speaking to each other in the voice of various characters to address real-life problems.

As he got older, Owen began to use the voice of various Disney sidekicks to understand the world around him. Speaking in his own voice, he could sometimes seem confused or shut down, but when he mimicked one of his favorite characters he could access insights about people and situations that were “otherwise inaccessible to him,” his father wrote. Eventually the family began working with therapist Dan Griffin (a Slate contributor) to help Owen use the scripts more creatively. He stayed in character but began to improvise, developing a comfortable way to express his inner thoughts.

As it happens, my son Jacob has also seen Griffin, who is based in Maryland. And while Jacob has a much milder form of autism than Owen, he’s certainly had his affinities over the years, starting at a very young age with letters and graduating lately, at age 10, to Minecraft. I spend a lot of evenings talking to my son about Minecraft, and I get caught up in the same worry as many parents in my situation: Am I helping or hurting him by indulging this obsession? Should I connect with my son over his favorite subject or let him know that soliloquies about Minecraft strategy are not usually a successful path to friendship?

To help answer this, I recently sat down with Ron, his wife, Cornelia, and Griffin in Griffin’s office. I wanted to explore how they came to the Disney insight, which overturns much of what we think about how an autistic brain works; how they managed to harness this insight for therapy; and finally, to find out whether there was a broader lesson that parents of children on the spectrum—and maybe even all parents—could draw from their experience. More specifically (and selfishly), I wanted to know how to make the most of my nightly Minecraft bonding time.

Ron Suskind: It started when Owen was about 6 1/2, and we’d have these basement sessions.

Cornelia Suskind: At that point he was much less flexible, so if he wanted to watch The Jungle Book, The Jungle Book it was. But year by year, he started to become more talkative when we just watched the movies. We’d be sitting and watching, and while all eyes were on the screen he was settled and available and we were all sharing the same context, so he could answer questions related to the movie. Side-by-side interactions.

Slate: Did you mention his Disney obsession to your therapists back then?

Ron: Everyone we worked with knew about it. But the general thinking was that it was best to tamp it down and get to more pragmatic speech and building skills in all the areas where he had huge deficits.

Cornelia: We got a really poignant letter from one of his teachers this week saying, “I really wish I’d listened to you guys and believed you when you told me all about Owen and Disney and not bought the party line!” Things could have been very different. But no one really took it seriously before Dan.

Dan Griffin: I remember it to the day. We took a break from therapy. Usually Owen hightails it out of the office, and this time he stayed. And you guys did a scene, with Iago [from Aladdin], I think. And suddenly there was this whole ionic charge in the room. You were much more engaged. He was much more engaged. It seemed like anything was possible. There was pure connection and pure joy, and it hit me pretty quick, we’ve got to be able to exploit this!

Ron: I’ll tell you what it was. It was the scene where Iago says, OK, “So you marry the princess and you become the chump husband.” Owen did that one. And I’d say, as Jafar, “I love the way your foul little mind works!”

Griffin: Yeah, my head was spinning a little. What caught me is that it kept him super-focused on something he would ordinarily not find that interesting, or he would find confusing—multiple ambivalent feelings, subterfuge, loving a girl but lying to her.

Ron: He could speak much more naturally in a sidekick’s voice than in his own. I remember Cornelia, Dan, and I really feeling our way around this thing. Is there any precedent for this? I remember Dan researching this and discovering little out there that applied, that could give us a framework.

Slate: Did your work become more systematic over time?

Griffin: Cornelia would come up with pretty pragmatic questions based on what was happening at home, and then Ron and I would meet before sessions and think, “How can we enlist some of these characters to broaden Owen’s perspective on this?” He didn’t like to do social cognition work, but if we could do it through a character’s eyes he would find it irresistible.

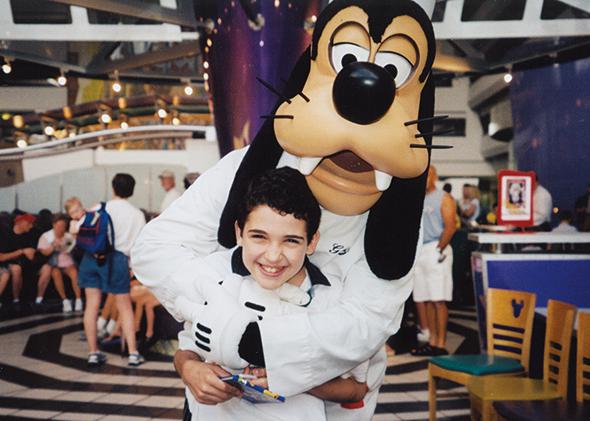

Photo courtesy Ron Suskind

Ron: Dan got to be very good at the scenes. He basically watched more Disney movies than any man his age should ever watch.

Griffin: Hey, it got me away from my Barbie collection.

Ron: Owen would start with a script and then we would add to it. Dan would throw in a voice and I would throw in a voice. I would say something as Merlin [from The Sword in the Stone] and Dan would respond as Arthur.

Griffin: And Owen would do things he would normally avoid. He would get into motives—why people respond this way to this person. It felt similar to me to what I did in my 20s. I was really into biographies then, learning how people go through dilemmas, and what they do with it. It seems like every person has their pantheon—the Bible, Hollywood, Greek myths, Shakespeare—their way of understanding the world. And this was Owen’s.

Cornelia: There was a period in ninth or 10th grade when Owen was really shutting down. It was after he’d been bullied, and he really didn’t want to grow up or take on any of the trappings of teenagerdom. Of dating, or having a job.

Ron: So I came up with the idea of having him use the voice of the sidekicks to solve the problem for a boy like Owen. Dan immediately got it. He gets up real close and says, “Let’s say there’s a boy like you. He’s a little different. He’s struggling and going through tough times and he wants to go backwards.” And without skipping a beat, Owen says, “I would prefer Merlin,” and starts doing this whole riff as Merlin about how he turned Arthur into a fish, and remember, the more you swim, the more you’ll learn, and on and on. And Dan looked at me with a “that’s not in the movie” look. And that’s when we realized he could improvise on cue and use the characters to tap into his inner voice and tell us what was really going on. He ended up in this strange middle ground between the movies and his life, and Dan and I could get into that space and shape it and guide it.

Griffin: Before that he had such an allegiance to the script and the characters that he thought, “Who am I to add anything?’” Cornelia had said he fussed with scripts at home, typing up some new scenes. But he’d done it secretly. With this shift it became exegesis, and he began to play with the scripts.

Ron: The key was to get him to use the holy writ as a springboard and improvise. That brought out a very, very fertile voice. His internal voice became external and we could hear it and shape it. It was like he felt relief, that he had found a way to talk to himself. That was the moment he started to self-heal.

Griffin: Remember when he talked about the girlfriend?

Ron: Yeah, Dan was waiting for this for a very long time, and he almost did a backflip when he heard it. Owen did this very knowing, interpretive explanation of what he was doing with her. He had raced through all the romantic Disney movies and settled on Aladdin, how he gave Jasmine her space, let her make her own choices.

Griffin: And we were verklempt! That was the gold ring, because he was away at school at the time, so he was doing this creative application of the movies in the right situation, without any prompting from us!

Ron: Then Dan says, “The thing is, you really have to know how she feels.” And Owen says, “I have something for that.” He says he listens to a song from Quest for Camelot called “Looking Through Your Eyes.” And Owen says, “I sing that song every morning to remember to see the world through Emily’s eyes.” And at this point Dan and I are crying.

Griffin: Yeah, it got sloppy.

Slate: Have you talked to any other experts about your experience? What do they say now?

Ron: Many of them had the reaction that this is a reversing of the telescope, that this 20-year improvisational experiment in the Suskind household seems to indicate that maybe we weren’t seeing these affinities with the proper lens. It creates kind of a restart button on this whole issue, that these behaviors can be seen as a pathway and not a prison if used properly. That how a child who engages with an affinity can reveal their capabilities, not just limitations.

Cornelia: Obviously we’re not saying sit the kid in front of the screen and see you later. As soon as we figured out this is where Owen lived, we all dove in.

Ron: We were interacting and feeling all the good stuff that makes all human beings want to bend toward the sunlight, and we could bend together.

Griffin: Fortunately he picked Disney and not Peyton Place. He picked something anyone could enjoy and a language that’s understood all over the world.

Slate: But what if a kid’s obsession can’t be mined so easily for lessons on human interaction. Train schedules, let’s say, or Minecraft?

Griffin: The key is to think, “How can I enter this world and begin to think and explore jointly with this kid?” Take Minecraft. You can go from talking about construction to cities to the problems of cities to overcrowding to “How do people who are pushed together learn to get along?” The point is to convey: I respect what makes your tail wag. I want to know about it, and I want my tail to wag along with yours.

Ron: It’s just so important, because these kids are investing so much in their affinity. You and I are allowed our passions and these kids are not. And the fact is, they are not going to get to so much else if their passion is cut off. This story is for all kids out there who are nontraditional learners, who can’t hit the bell or who don’t measure up by the yardstick of the meritocracy. This is a story for every one of those people.

Griffin: Is Owen enjoying the buzz from the book?

Ron: He’s having a ball. But you know, he’s context-blind, so he’s not good on issues of scale. So we say, “The world is touched by you.” And he says, “That’s great. I’m going bowling, See you later!”